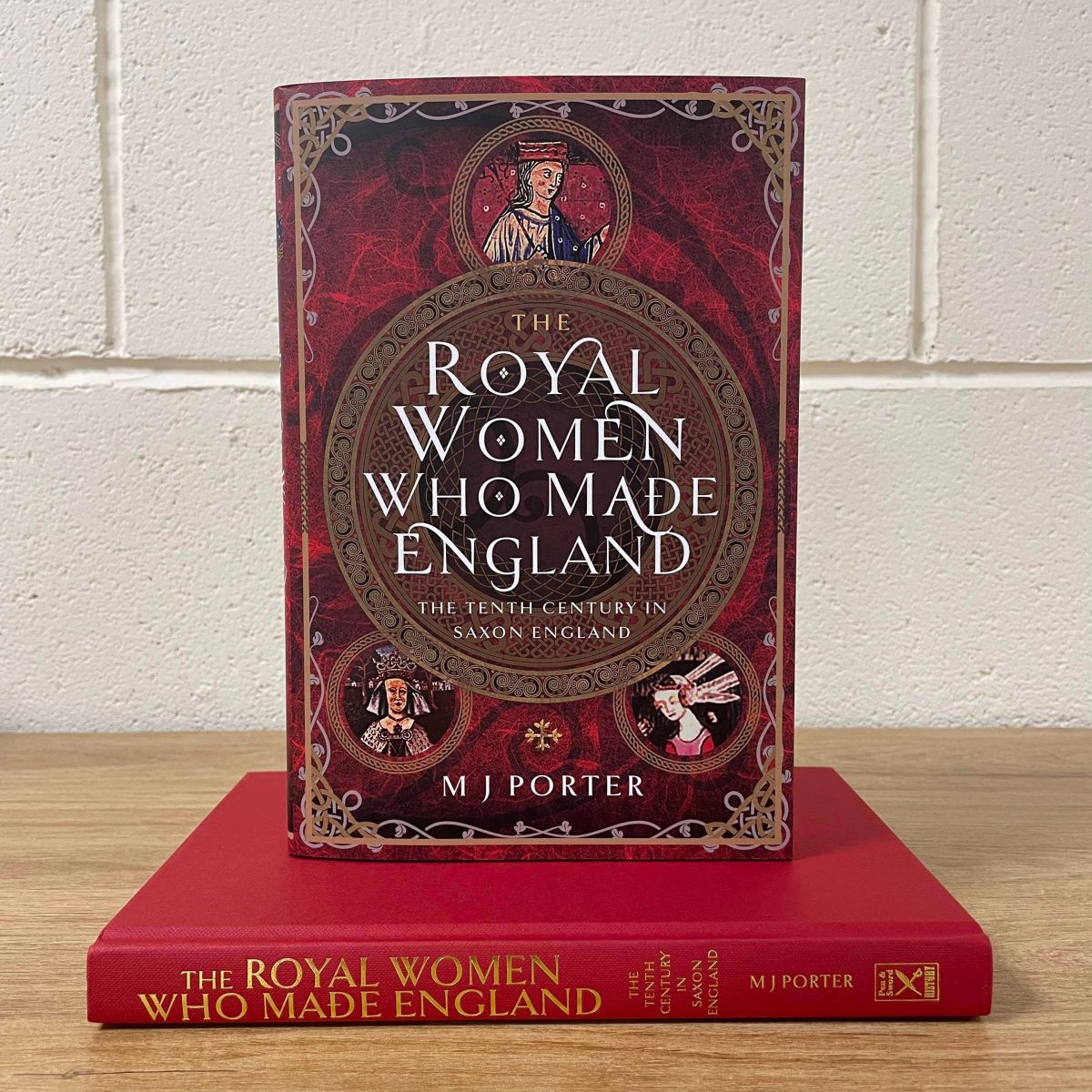

It feels like I’ve been talking about this book forever, but the day is finally upon us. The Royal Women Who Made England is available in hardback in the UK and US from today, and also in Kind

If you’ve been hiding from me for the last few months, you might be wondering what this is all about. So here goes.

Throughout the tenth century, England, as it would be recognised today, formed. No longer many Saxon kingdoms, but rather, just England. Yet, this development masks much in the century in which the Viking raiders were seemingly driven from England’s shores by Alfred, his children and grandchildren, only to return during the reign of his great, great-grandson, the much-maligned Æthelred II.

Not one but two kings would be murdered, others would die at a young age, and a child would be named king on four occasions. Two kings would never marry, and a third would be forcefully divorced from his wife. Yet, the development towards ‘England’ did not stop. At no point did it truly fracture back into its constituent parts. Who then ensured this stability? To whom did the witan turn when kings died, and children were raised to the kingship?

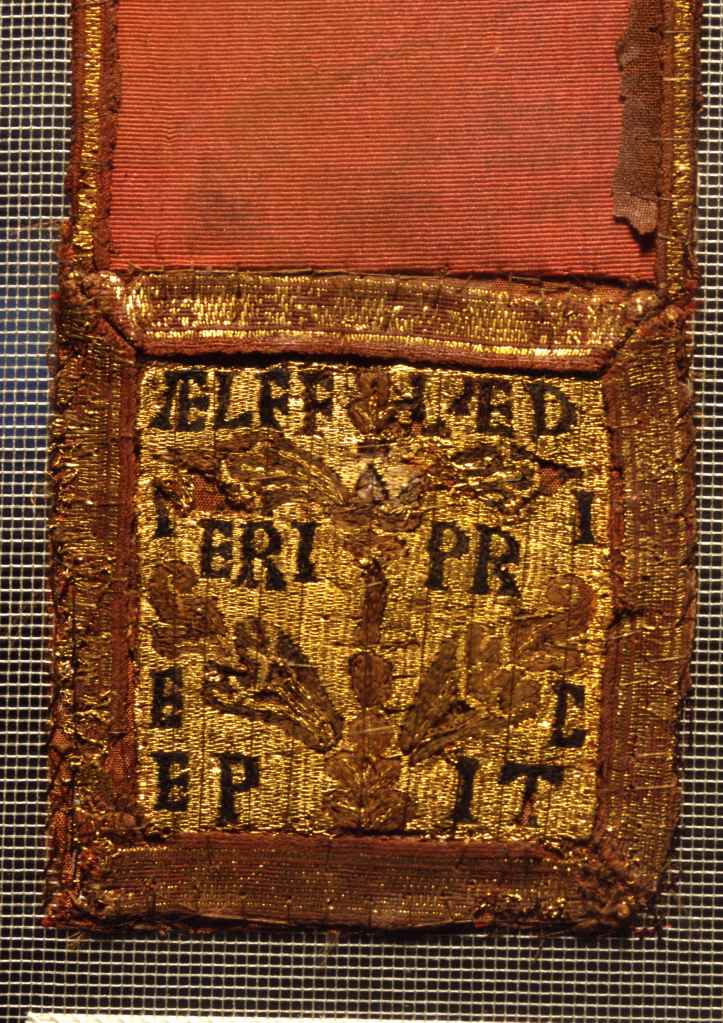

The royal woman of the House of Wessex came into prominence during the century, perhaps the most well-known being Æthelflæd, daughter of King Alfred. Perhaps the most maligned being Ælfthryth (Elfrida), accused of murdering her stepson to clear the path to the kingdom for her son, Æthelred II, but there were many more women, rich and powerful in their own right, where their names and landholdings can be traced in the scant historical record.

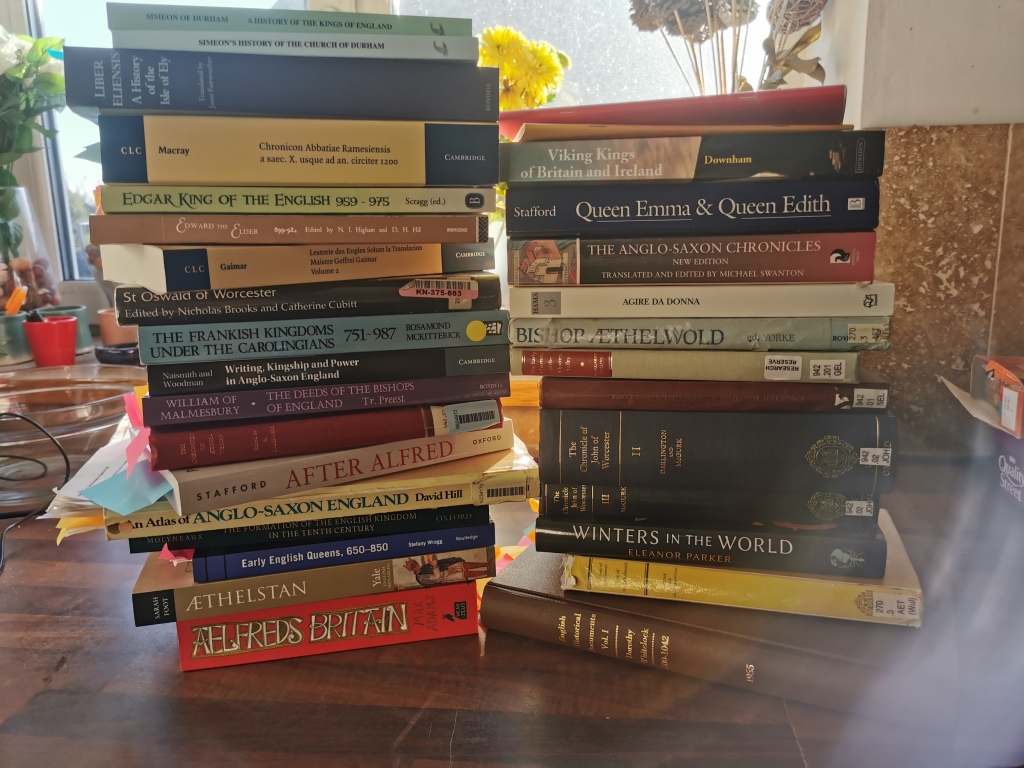

Using contemporary source material, The Royal Women Who Made England can be plucked from the obscurity that has seen their names and deeds lost, even within a generation of their own lives.

So, who were these royal women? While some of us will know Æthelflæd, the Lady of Mercia, either because I think she is one of THE most famous Saxon women, or because of The Last Kingdom TV series and books, but she is merely one of many.

I’ve fictionalised Elfrida and her contemporaries, Eadgifu, the third wife of Edward the Elder and also some of his daughters, as well as Ælfwynn, the daughter of Æthelflæd. My first non-fiction title is me sharing my research that these stories are based upon.

I’ve also ‘found’ many other women of the period who have left some sort of physical reminder, mostly in charters or because their wills have survived.

In total, I discuss over twenty women directly involved with the royal family, either by birth or marriage, and also a further forty, who appear in the sources. I also take a good look at what these sources are and how they perhaps aren’t always as reliable as we might hope. I make an attempt to ‘place’ these women in the known historical events of the period. And draw some conclusions, which surprised even me.

You can find some of my blog posts about these women below.

The daughters of Edward the Elder.

The other daughters of Edward the Elder

Listen to me talk about the Chronicon of Æthelweard (about 6 minutes).