A few weeks ago, I was granted exclusive access to King Coelwulf.

A few weeks ago, I was granted exclusive access to King Coelwulf. Here’s what the enigmatic king of Mercia had to say.

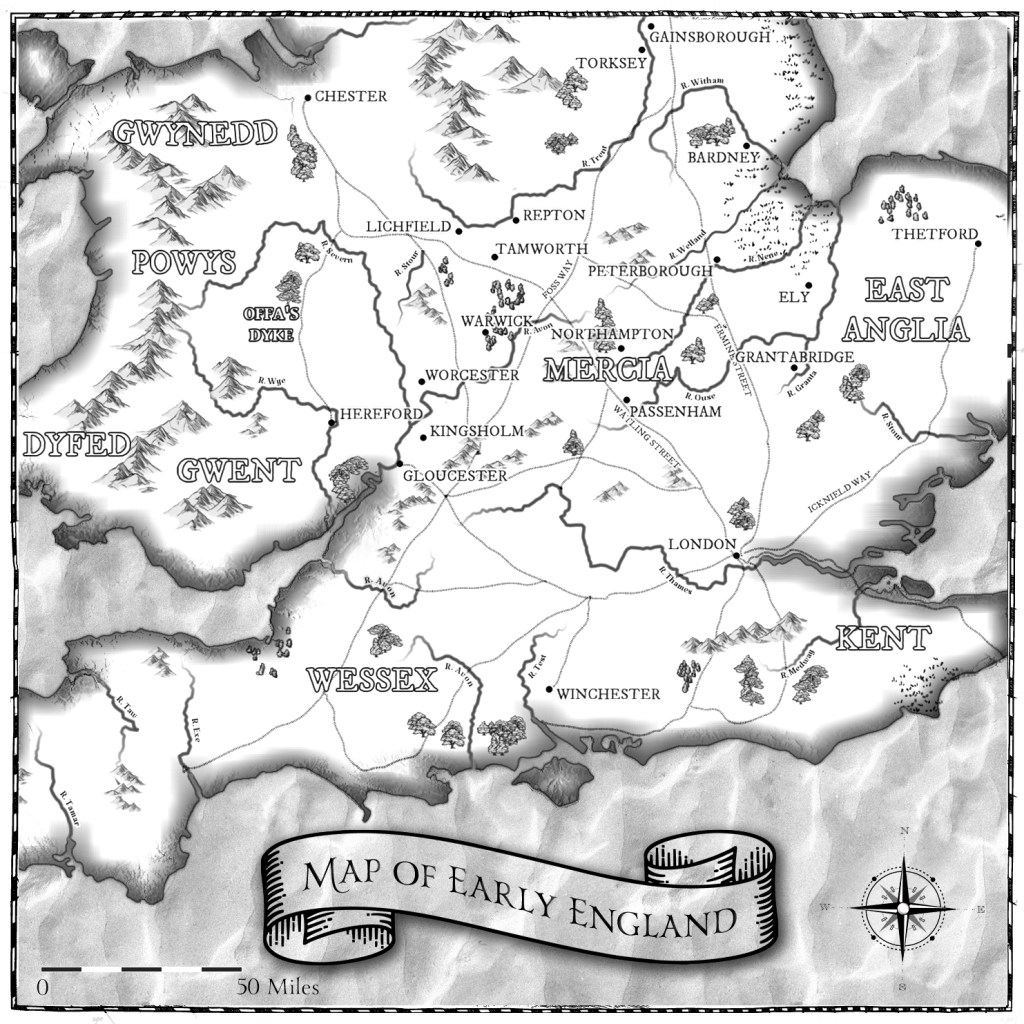

King Coelwulf, thanks for allowing me entry into your stronghold at Northampton. It’s quite interesting to be at the heart of the Mercian defence against the Raiders. Now, can you tell me why people should want to read about you?

“Well, I’m not saying that they will. I mean, if they’re like me, then they probably don’t have time to be reading a story. I’ve got bodies to bury, Raiders to hunt down, and a kingdom to rule. I would tell anyone to spend their time more wisely than reading a book. That sort of thing is for the monks and the clerics, not warriors trying to defend a kingdom.”

Ah, well, in that case, thank you for finding the time to speak to me.

“I didn’t have much choice. Or rather, I was advised it would be a good use of my time, by my Aunt, Lady Cyneswith.”

Well, Lady Cyneswith is a wise woman, and I’m grateful that she’s encouraged you to speak to me.

“She is a highly intelligent woman. Braver than many men when it comes to the Raiders, and skilled when it comes to healing injuries of the body, as well as the mind.”

And her dogs have very interesting names, what was it again? Wiglaf and Berhtwulf, surely the names of old Mercian kings? Men who usurped the ruling line from your family?

“Oh really. I’d never realised. Funny, that.”

Ah, well, moving on, could you tell me about your books? I’m sure my readers would love to hear about it.

“Nothing to say really. Same old, same old. Raiders to evade, Raiders to find, Raiders to kill, a kingdom to keep whole. It’s a grand old bloody mess. I swear, I’ve barely managed to scrub the grime and body fluids from my sword and seax. Or rather, Wulfhere has. He’s a good lad. Quick on his feet. He’s one of my squires. Couldn’t do it without him.

That’s interesting that you should mention your squire, did you say? I wouldn’t have expected you to even know the lad’s name. After all, you are the king of Mercia, surely your squire is beneath you. Are there any more of your warriors you’d like to mention by name?

“Of course there are. I’d name them all if I had the time, which I don’t, just to make you aware. I’ve got to go to a crown-wearing ceremony shortly. But, I’ll mention a few, just to keep you happy. And you should know that no man is ever above knowing the names of those who serve him. Remember that.

But, I’ll mention some of my warriors by name. If only because it’ll infuriate some of them. Edmund, he’s my right-hand man, a skilled warrior, missing an eye these days, but it’s not stopped him, not at all. His brother, Hereman. Well, where do I start? Hereman does things no one would consider, in the heat of battle, and he’s a lucky b……. man, sorry, he’s a lucky man. And then there’s Icel. He’s lived through more battles than any of the rest of my warriors. I almost pity the Raiders who come against him. None of them live for much longer.

And Pybba. You know, he fights one handed now, and the Raiders seem to think he’s easy picking, but he’s not. Not at all. And, I can’t not mention Rudolf. He’s the youngest of my warriors, but his skill is phenomenal, not that you can tell him that. Cheeky b……, sorry cheeky young man. But, all of my warriors are good men, and we mourn them when they fall in battle, but more importantly, we avenge them all. All of them. No Raider should take the life of a Mercian without realising they’ve just ensured their own death.

Yes, I’ve heard that you avenge your men, with quite bloody means. And Edmund, there’s a suggestion that he’s a scop, a man who commits the deeds of the fallen to words? That fascinates me, as someone who also makes a living from using words.

“Well, Edmund has some small skills with words, but he honours our fallen warriors by weaving them into the song of my warriors. In fifty years, when we’re all dead and gone, our legend will live on, thanks to Edmund, and his words.

Can I ask you about Alfred, in Wessex? Have you met him? Do you think he’s doing a good job in keeping the Raiders out of Wessex?

“I’ve never met him. Couldn’t say either way. It’s not for me to comment on a fellow king. We’re all after the same thing. Kill the f……, sorry, kill the b……., sorry, kill the enemy. All of them, until Mercia is safe once more. And Wessex, if you’re from there.”

Well, it looks like you’re needed. Is that your crown?

“Yes, and now I need to go and perform some ceremonial task. It’ll take a long time, no doubt. Make sure you have an escort when you leave here. I wouldn’t put it passed the f……, sorry, the Raiders, to be keeping a keen eye on the bridge over the Nene.

Thank you for your concern, and yes, I’ll make sure I do. Good luck with the new book.

“I don’t need luck. I just need to kill all the b……., sorry, Raiders.

As you can tell, King Coelwulf was a very busy man. But I found him to be honourable and worthy of leading the Mercians against our persistent enemy. Long live the king.