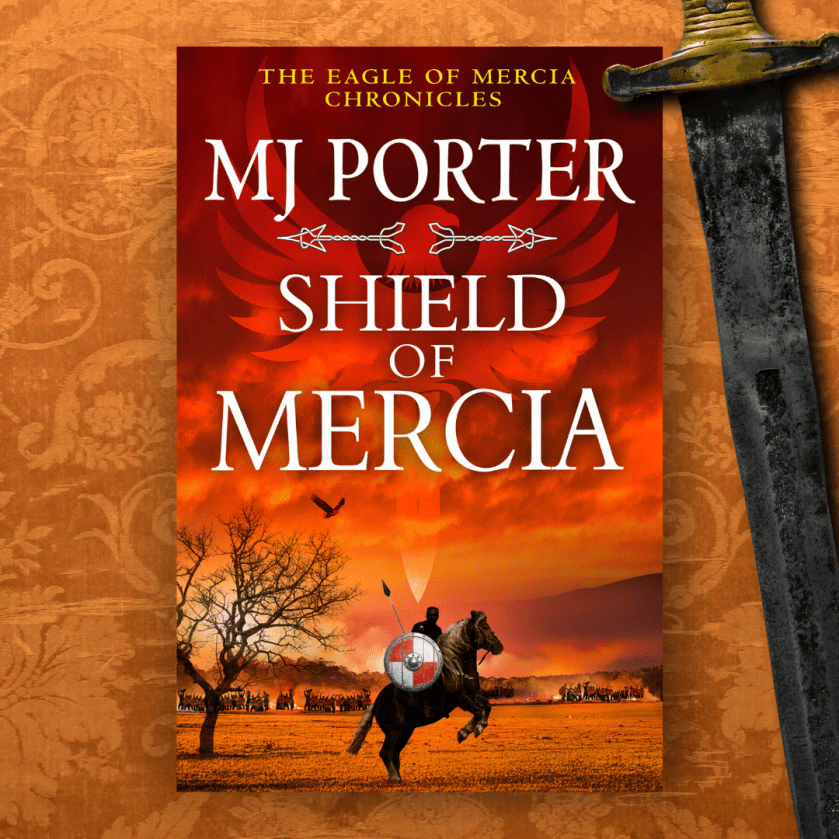

Here’s the blurb for 757

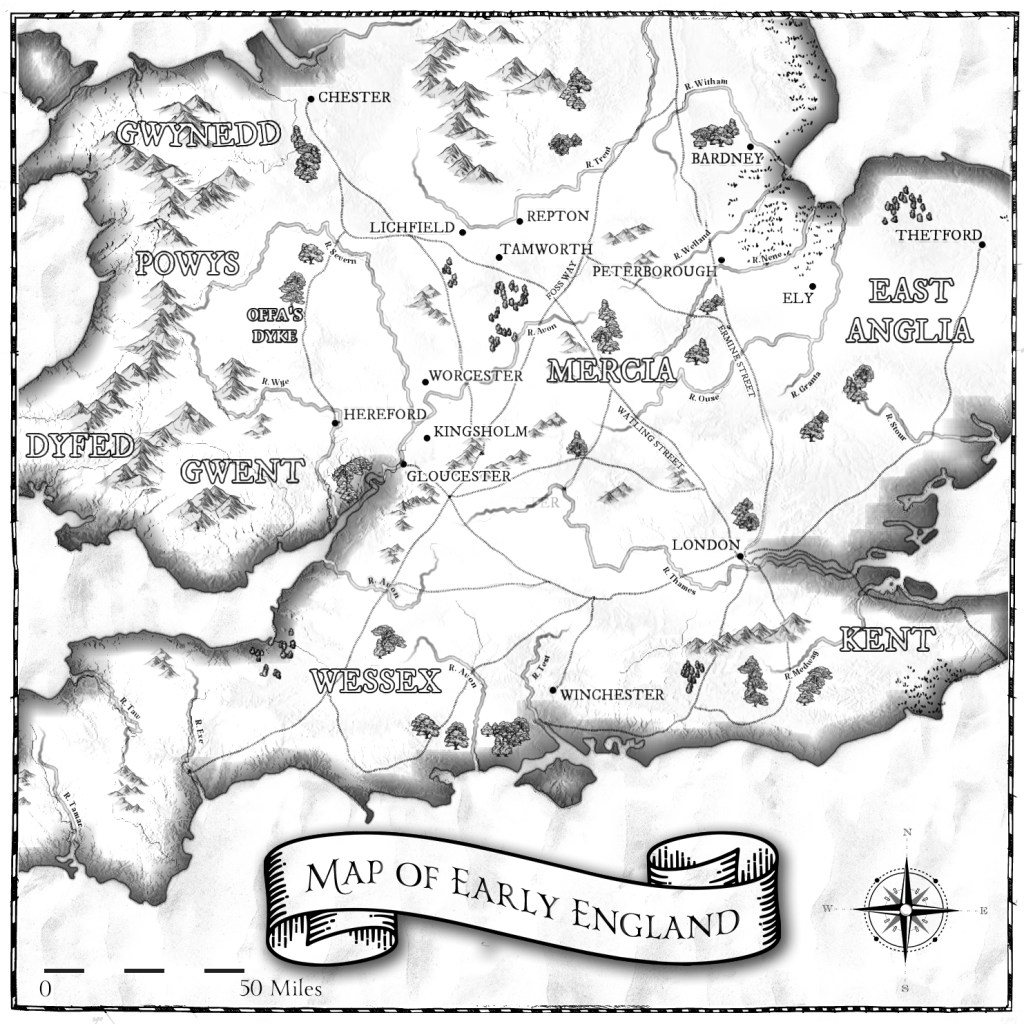

This is Mercia. The year is 757.

A king will fall. A king will rise.

But first, civil war will rage.

King Æthelbald’s forty-year vice-like rule over Mercia has been rigid. But he lacks a legitimate heir despite his insatiable bedchamber antics.

Offa must stand hostage to his family’s good behaviour, when his father missteps in removing his mother from Æthelbald’s bed. Shockingly, his younger sister now replaces her.

But the king isn’t finished with his denigration of Offa’s noble House. When his parents are traitorously killed, Offa’s resentment grows, compounded by the ridicule heaped on him by King Æthelbald’s oathsworn warriors.

With the king’s health deteriorating, the matter of the succession becomes paramount. There are plenty who share a claim to the kingship.

Discord threatens to fracture the mighty realm, and those with sword and shield, seax and spear are prepared to risk it all to be the future king of Mercia.

The background to the House of Mercia – AKA what happens after the Gods and Kings trilogy

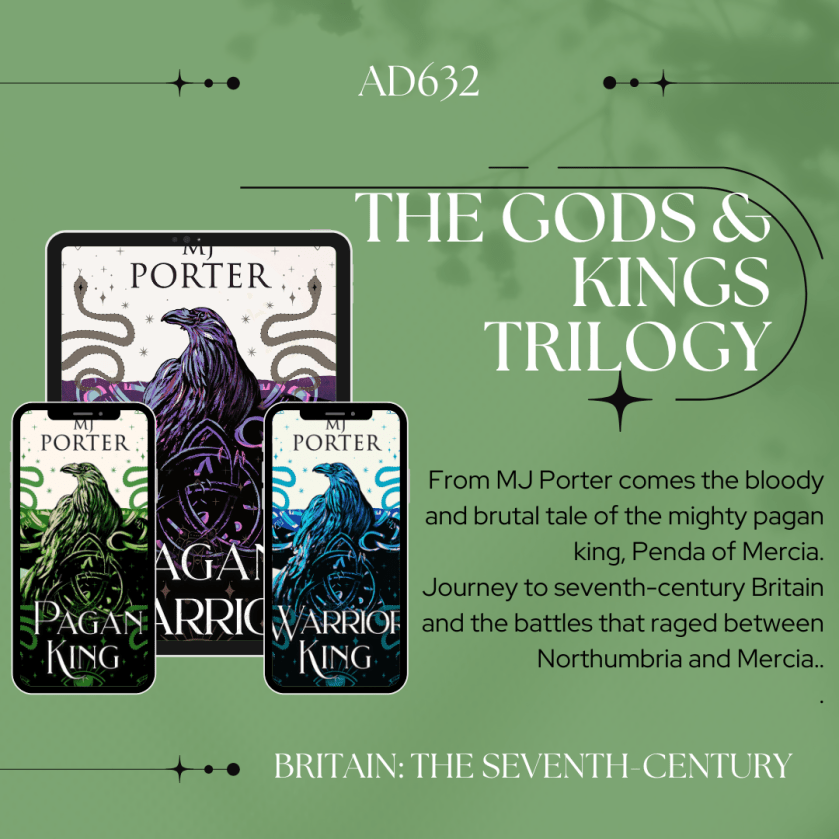

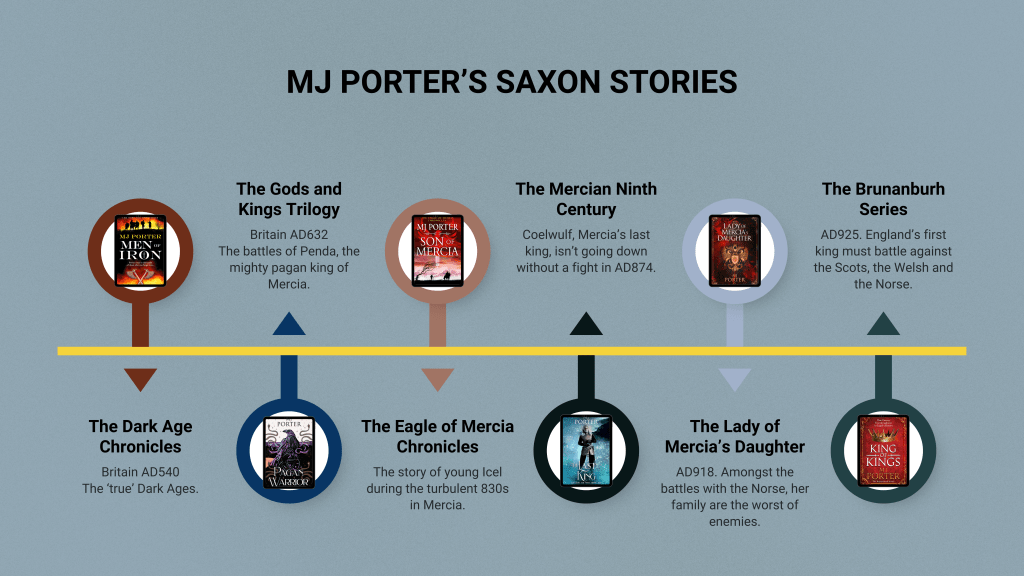

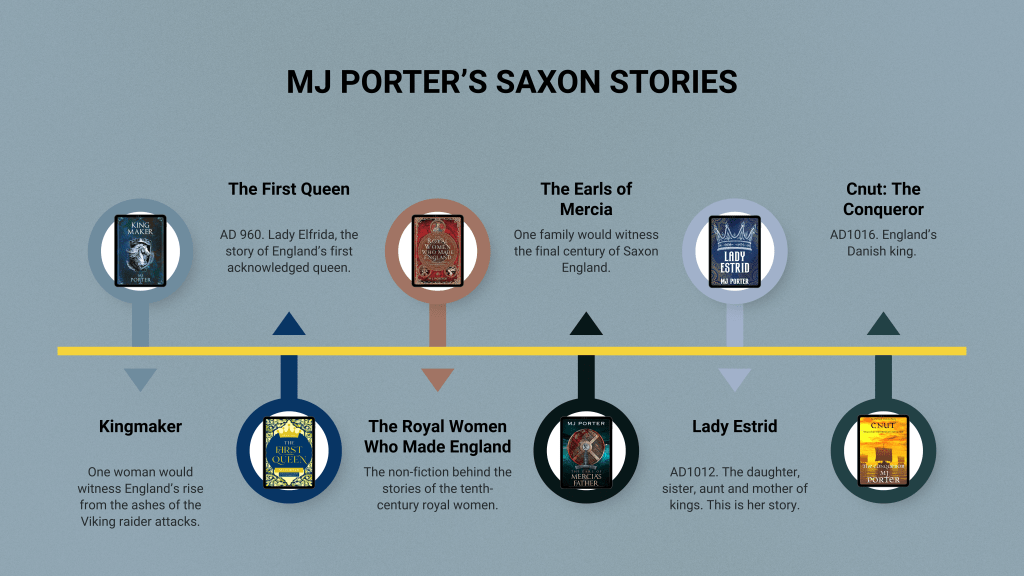

If you’ve been with me for a while, you’ll know I’ve written about Mercia in many of the centuries of its existence. Until now, I haven’t ventured into the eighth century and many of you might not have read the Gods and Kings Trilogy (there is still time to get it read before House of Mercia hits the shelves), and even if you have, there’s a century between the final events of Warrior King (655) and the beginning of 757, the first book in The House of Mercia series. So, I thought it was time to add some flavour to this century.

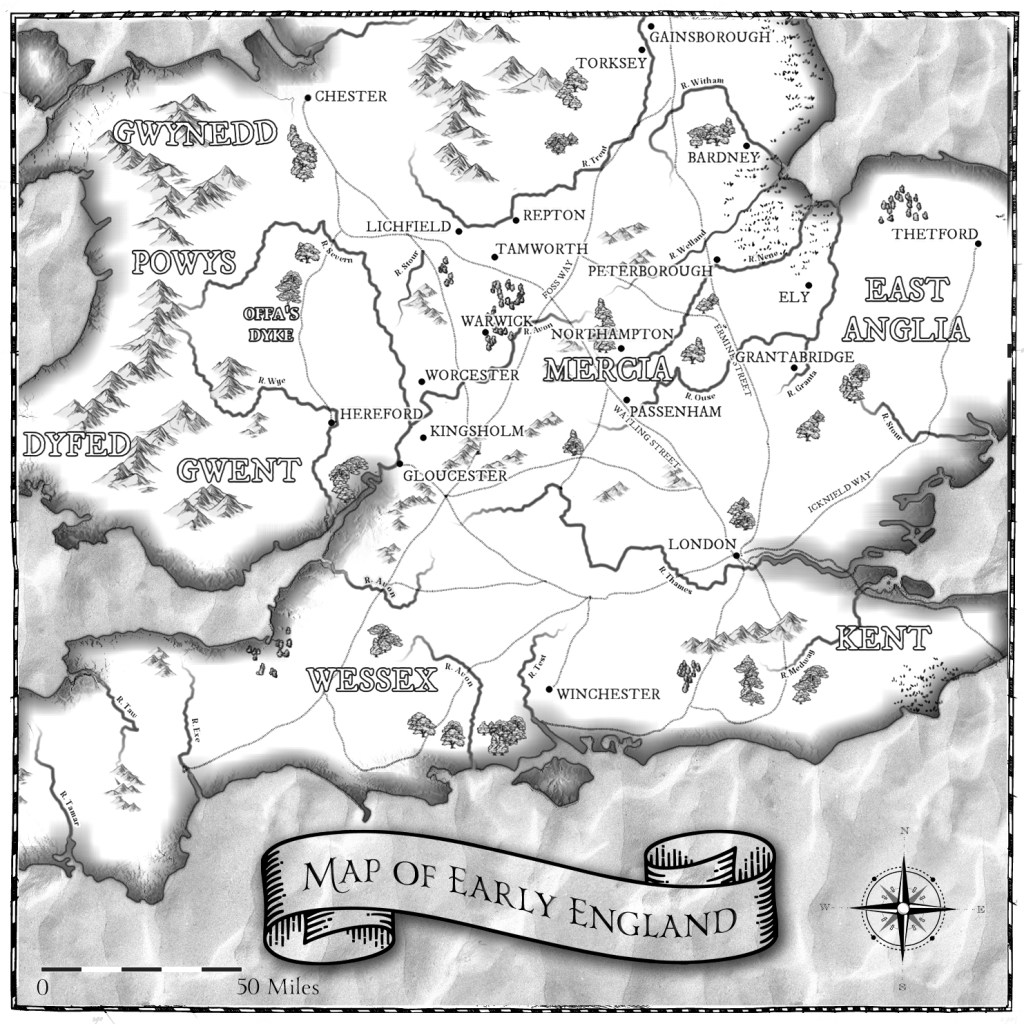

The Gods and Kings trilogy follows a collection of mighty warrior kings in Saxon England from the 620s to the 650s, as the ‘larger’ Saxon kingdoms were forming – (Northumbria from Bernicia and Deira) (Mercia from the heartland of Mercia centred around the area of the Tomsæte (yep, they get a mention in the Dark Age Chronicles) to include the kingdoms of the Hwicce, the Magonsæte, Lindsey and Elmet). Of these, it’s the brother kings Eowa and Penda that most concern us, as they were both kings of Mercia, claiming descent through Pybba (and it’s this genealogy that leads us back to Wærmund (from the Dark Age Chronicles), and even mentions an Icel (do you see what I did there?)

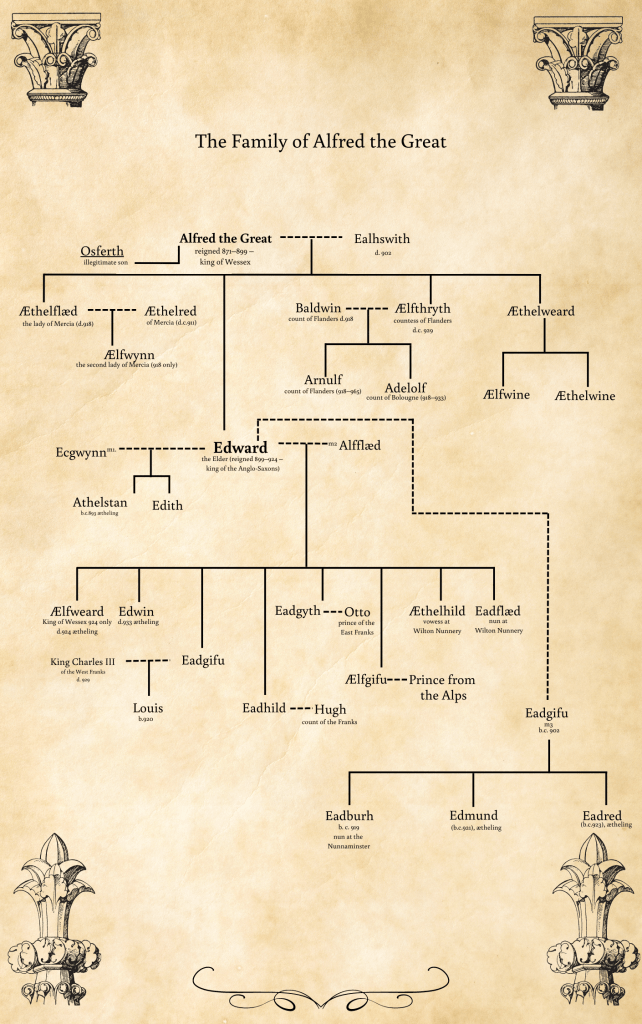

Whatever the exact relationship between the two brothers (as explored in the Gods and Kings trilogy), they ruled one after another, Eowa falling at the battle of Maserfeld in 642, against the Northumbrians and Penda outliving him to rule until his death in 655. (There’s also another shadowy brother, possibly sharing a father but not a mother, Cuthwalh, who is important. He was never a king of Mercia, but his existence (if he existed) is very relevant to events in the eighth and indeed, ninth century.)

Eowa had children when he died. Penda also had children. As the brother who ruled second, the kingdom of Mercia was bequeathed to Penda’s children, first Pæda (his son, who didn’t rule for very long), then Wulfhere (Penda’s son 658-675), Æthelred (Penda’s son, who abdicated in 704 and died in 716), Ceonred (Wulfhere’s son, who ruled from 704-709 and abdicated to travel to Rome), Ceolred (Æthelred’s son, from 709-716) and then Coelwald, who briefly succeeds and is assumed to be another son of Æthelred, until the line passes to that descended from Eowa, through his son or daughter (I think in the Gods and Kings trilogy I’ve made Alweo a daughter), Alweo, in the figure of Æthelbald, while Offa’s line descended through the other brother, Osmod. (Looking at this, I can’t help thinking that a little less religious fervour might have been to the advantage of the ruling line of Mercia – but of course, this was the time of conversion – Wulfhere is said to have been the first Christian king of Mercia (although Pæda also converted, but sadly, met a sticky end). The relationship between Mercia and Northumbria at the time was, I think ‘messy.’

So, that all seems quite complicated. At this time, Mercia was very often in conflict with the kingdom of Northumbria, and indeed, a number of assassinations occur. Pæda is killed by his wife (a Northumbrian). A daughter of Penda also marries one of Oswiu’s sons, Alhfrith. The Northumbrian king, Oswiu (the cheek of it), then briefly rules Mercia, until he’s driven from Mercia by Wulfhere (Penda’s son), who then becomes king. Wulfhere endeavoured to defeat the Northumbrians, then being ruled by Ecgfrith (half-brother of Alhfrith), the son of Oswiu, but failed, whereas Wulfhere’s brother, Æthelred, was later successful. These two battles fascinate me, and if you’ve read my short story, A Father’s Son, which you can download here and join my mailing list) it’s the very beginning of a project where I hoped to tell the story of these two battles, the one where Northumbria is triumphant, the other where Mercia sets the record straight, but I’ve never quite found the time.

This succinct account then brings us to Æthelbald, an old man by the time The House of Mercia takes place, but one who evidently ruled well throughout his 41 years – quite an astonishing feat at the time. It’s believed he lived for some time in exile before becoming king, perhaps in the kingdom of the East Angles, when her king, Ælfwald, ruled. It seems evident, therefore, that there was some discord in Mercia at the time between the potential ruling houses. While Eowa’s son hadn’t endeavoured to claim the kingship of Mercia (I think he died, but maybe that was what I had happen in the Gods and Kings trilogy), his descendants were more ambitious. So, this brings us to the events of 757, the first book in the House of Mercia series. What comes next will form the narrative.

Posts

Stay up to date with the latest from the blog.