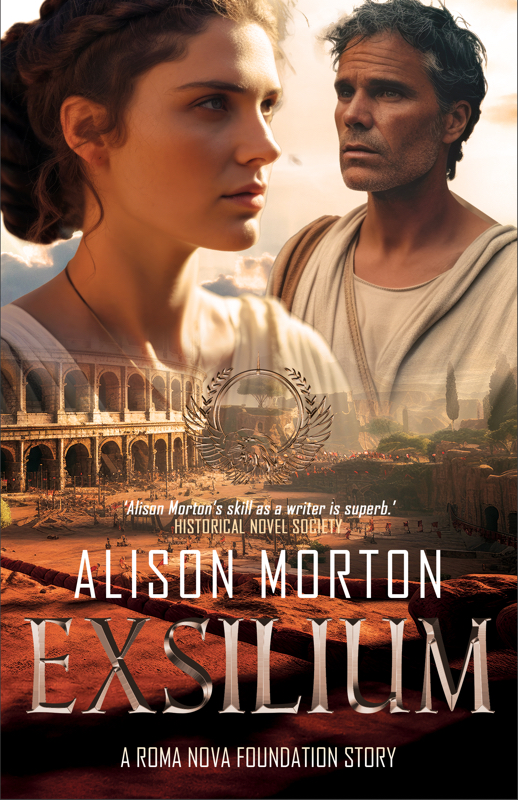

I’m delighted to welcome Alison Morton and her new book, EXSILIUM, part of the Roma Nova series, to the blog with a guest post.

Guest Post

When we think of Romans, two images immediately spring to mind. The first is a fierce helmeted solder wearing iron bands of segmented armour across his torso over a red tunic that only just covers his knees and with hobnail marching boots on his feet. He carries a spear, gladius ad dagger as weapons and a large rectangular shield which he uses in clever formations with his comrades.

The second is a man draped in a splendid toga making a clever speech in the Senate. His ‘womenfolk’ would be demurely dressed in tunic and mantle, often accompanied by a slave in a simple tunic.

Well, yes and no.

Let’s look at the military

The earliest proven use of this segmented armour is in 9 BC with a suggestion of possibly as early as 53 BC; the latest in the last quarter of the third century AD. In some later depictions, such as on the Arch of Constantine (AD 315), segmented armour is seen, but scholars seem to think it was more for ceremonial show rather than reflecting what was used at the time by soldiers in the field.

Rome had become a republic in 509 BC after throwing out its kings who had – according to legend – reigned for two hundred and fifty years before that. So for the first seven centuries of its history, there was no ‘typically Roman’ segmented armour. The very early republican soldiers would probably have worn bronze helmets, breastplate and greaves and carried a round leather or large circular bronze-plated wooden shield, and fought with a spear, sword and dagger.

According to the ancient Greek historian Polybius, whose Histories written around the 140s BC are the earliest substantial account still existing of the Republic, Roman cavalry was originally unarmoured; the soldiers only wore a tunic and were armed with a light spear and ox-hide shield which were of low quality and quickly deteriorated in action.

In contrast to the lorica segmentata beloved by Hollywood, the more pedestrian and expensive chain mail (lorica hamata) was in use for over 600 years (3rd century BC to 4th century AD) and scale armour (lorica squamata) during the Roman Republic and in later periods. The latter was made from small metal scales sewn to a fabric backing and is typically seen on depictions of signiferes (standard bearers), centurions, cavalry troops, and auxiliary infantry, as well as ordinary legionaries. On occasion, even the emperor would be depicted wearing the lorica squamata. It’s not known exactly when the Romans adopted this type of armour, but it remained in use for about eight centuries.

Fast forward to the fourth century… In contrast to the earlier segmentata plate armour, which afforded no protection for the arms or below the hips, some pictorial and sculptural representations of Late Roman soldiers show mail or scale armour giving more extensive protection. These types of armour had full-length sleeves and were long enough to protect the thighs and other essential parts of the body(!).

In northern Europe, long-sleeved tunics, trousers (bracae), socks (worn inside the caligae) and laced boots had been commonly worn in winter from the 1st century onwards. During the 3rd century, these became much more widespread, with the alternative of leggings, even in Mediterranean provinces also. By the late fourth century, both were standard wear. Apart from more colourful and decorated clothing generally, a distinctive part of a soldier’s fourth century costume was a type of round, brimless hat known as the pannonian cap (pileus pannonicus).

All change for civilian men

In the Republican and early imperial periods, Roman men typically wore short-sleeved or sleeveless, knee-length tunics. On formal occasions, adult male citizens could wear a woollen toga draped over their tunic. But from at least the late Republic onward, the upper classes favoured ever longer and larger togas, increasingly unsuited to manual work or physically active leisure. Togas were expensive, heavy, hot and sweaty, hard to keep clean, costly to launder and challenging to wear correctly. They were best suited to stately processions, oratory, sitting in the theatre or circus, and self-display among peers and inferiors. The vast majority of citizens had to work for a living, and avoided wearing the toga whenever possible. Several emperors tried to compel its use as the public dress of true Romanitas but none were particularly successful. The aristocracy clung to it as a mark of their prestige, but eventually abandoned it for the more comfortable and practical pallium.

By the end of the fourth century, clothing looked radically different and didn’t conform to our idea of ‘typically Roman’. In such a diverse empire, the adoption of provincial fashions perceived was viewed as attractively exotic, or simply more practical than traditional Italian Roman forms of dress. Clothing worn by soldiers and non-military government bureaucrats became highly decorated, with woven or embellished strips, clavi, and circular roundels, orbiculi, added to tunics and cloaks. These decorative elements usually comprised geometrical patterns and stylised plant motifs, but could include human or animal figures. The use of silk also increased steadily and most courtiers in late antiquity wore elaborate silk robes. Court officials as well as soldiers wore heavy military-style belts, revealing the increased militarisation of late Roman government. Trousers and leggings – considered barbarous garments worn by Germans and Persians – became more more common for civilian men in the latter days of the empire, although regarded by conservatives as a sign of cultural decay.

The toga, traditionally seen as the sign of a proper Roman, had never in reality been popular or practical. Most likely, its replacement in the East by the more comfortable pallium or paenula (a wool cloak) was a simple acknowledgement that the toga was generally no longer worn. However, it remained the official formal costume of the Roman senatorial elite. A law issued by co-emperors Gratian, Valentinian II and Theodosius I in 382 AD stated that while senators in the city of Rome may wear the paenula in daily life, they must wear the toga when attending their official duties. Failure to do so would result in the senator being stripped of rank and authority, and of the right to enter the Senate House. But it’s worth noting that in early medieval Europe, kings and aristocrats who dressed like the late Roman generals they sought to emulate, did not display themselves draped in togas.

And the women?

In early Republican Rome, both men and women wore togas but in mid-Republican times, the toga became a male-only garment. Only prostitutes wore a toga as a sign of their ‘infamy’. Typically, women and girls wore a longer, usually sleeved tunic for and married citizen women wore a mantle, usually wool, known as a palla, over a stola, a simple, long-sleeved, voluminous garment fastened at the shoulders that fell to cover the feet. In the early Roman Republic, the stola was reserved for patrician, i.e. aristocratic women as a sign of their status. Shortly before the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), the right to wear it was extended to plebeian matrons, and to freedwomen who had acquired the status of matron through marriage to a citizen.

But things had changed dramatically by the end of the fourth century. Women of that time wore belted long tunics decorated with full-length contrasting stripes – clavi – and braiding, with generous sleeves and, in cooler climates, narrow-sleeved underdresses. That Late Roman tunic, or dalmatica, was a generously cut T-shaped tunic with a slit neck, typically falling in (hopefully) graceful folds. Sleeves could be short, three-quarter or long and rectangular, which could be fairly narrow or quite wide. Wide sleeves were sometimes tied back, presumably for work, giving a butterfly’s wing effect.

The belt, worn under the bust, was often just a tied cord, or could be of plain or decoratively woven cloth and could have a central jewel, perhaps a brooch. As weather protection and ornament, ladies would, like their Republican predecessors, wear various sizes of mantle (palla or the smaller palliola), a rectangular piece of material cast elegantly over the shoulder like a scarf or draped around the body.

Some literature suggests both traditional pagan and Christian respectable ladies would cover their hair in the street but this was not universal.

Ladies would prefer mantles for travel rather than sagum style cloaks, but rural women and athletes were known to wear practical gear for weather protection and presumably camp followers might wear spare military cloaks. The expensive birrus britannicus, mentioned in Diocletian’s edict on maximum prices, was probably a heavy, long semi-circular hooded cape with front opening.

Clothing depended on the wearer’s wealth or poverty, their social status, on the ability to find or make fabric and on personal preference. Sometimes you took what was given when cast off by an older sibling. But over twelve centuries, while some things like tunics performed the same function, how Romans looked changed much more than we might imagine.

Here’s the Blurb

Exile – Living death to a Roman

AD 395. In a Christian Roman Empire, the penalty for holding true to the traditional gods is execution.

Maelia Mitela, her dead husband condemned as a pagan traitor, leaving her on the brink of ruin, grieves for her son lost to the Christians and is fearful of committing to another man.

Lucius Apulius, ex-military tribune, faithful to the old gods and fixed on his memories of his wife Julia’s homeland of Noricum, will risk everything to protect his children’s future.

Galla Apulia, loyal to her father and only too aware of not being the desired son, is desperate to escape Rome after the humiliation of betrayal by her feckless husband.

For all of them, the only way to survive is exile.

Buy Link

Meet the Author

Alison Morton writes award-winning thrillers featuring tough but compassionate heroines. Her ten-book Roma Nova series is set in an imaginary European country where a remnant of the Roman Empire has survived into the 21st century and is ruled by women who face conspiracy, revolution and heartache but use a sharp line in dialogue. The latest, EXSILIUM, plunges us back to the late 4th century, to the very foundation of Roma Nova.

She blends her fascination for Ancient Rome with six years’ military service and a life of reading crime, historical and thriller fiction. On the way, she collected a BA in modern languages and an MA in history.

Alison now lives in Poitou in France, the home of Mélisende, the heroine of her two contemporary thrillers, Double Identity and Double Pursuit.

Connect with the Author

Website: Blog: BlueSky: Newsletter:

Thank you so much, M J, for hosting EXSILIUM today. I hope your readers enjoy this piece about the changes in how Romans looked over the centuries.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Me too. So fascinating. 👍

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for hosting Alison Morton today, with such an interesting post!

Take care,

Cathie xx

The Coffee Pot Book Club

LikeLiked by 1 person