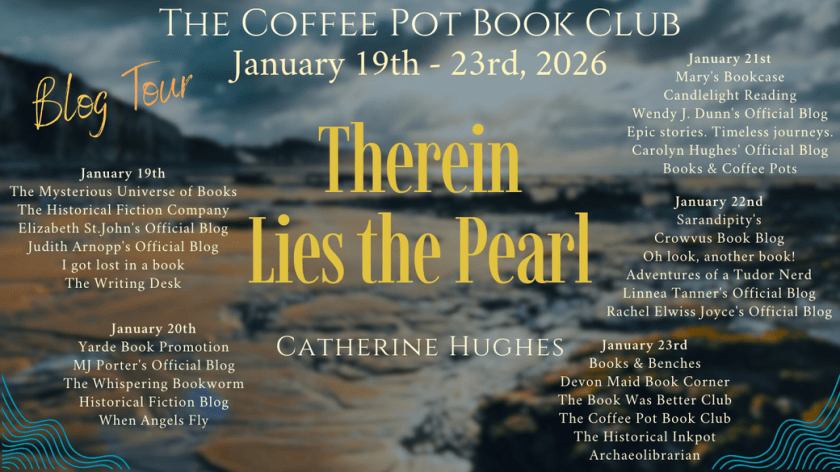

I’m delighted to welcome Catherine Hughes and her new book, Therin Lies the Pearl, to the blog with an excerpt.

Excerpt 3

Her voice lifted in confusion. “Father?”

Margaret had been breathing in the musky smell of the woodlands and the flowering anemone that lined their path when she saw her father’s body, as it was positioned in the saddle, tilt further and further toward the side.

That morning the family had left the inn and began traveling toward Favreshant, following a path made fragrant by the flowers and plants newly opened for spring. The weather did much to improve Margaret’s spirits as the sun shone brightly upon them from a clear, blue-domed sky. An occasional puffy cloud floated across the heavens but never did it linger long enough to diminish the warmth that embraced her. Walking with a bemused smile upon her face, Margaret surrendered to the charms of the countryside, relishing in the way the light accentuated the many shades of green that colored the leaves, the bushes, and the flower stems. A random look toward the front of the cavalcade snapped her pleasant daydream when she noticed the rider near the head of the train—her father—was about to fall.

Abandoning her usual sauntering walk, she broke into enormous strides trying to close the gap between her father and herself. The rapid turnover of her feet upon the soil alarmed the flock of yellowhammers who had been flitting about the blossoms. To escape the disruption, they rose higher and hovered above, waiting for the tumult to settle.

“Father!”

Her shout coincided with the loud thud of his body landing on solid ground, his head coming to rest in a patch of wildflowers.

Before Margaret reached him, she could see Gerhard was already there. He had carefully removed young Edgar from the saddle and then ran toward Edward, dropping to his knees for closer inspection.

Margaret skidded to a halt and took the same posture on the other side of her father’s fallen body. Hesitantly, she repeated again, “Father…?”

His lips parted but no sound issued forth.

After a quick glance in her direction, Gerhard moved closer to Edward, placing one hand beneath his master’s neck and bringing his own closer. “Edward! Edward, can you hear me?” Nothing. “Blink your eyes if you can hear me.” Gerhard’s voice cracked with worry, his usual composure gone. Because Gerhard had leaned so closely over her father’s head, Margaret had to slide further up toward his shoulder to be able to see whether or not her father had comprehended Gerhard’s words.

To her relief, she saw his eyelashes flutter—he understood! He was still there, he was still with them!

Gerhard continued. “Can you move your legs, my lord? Your arms? Just blink to let me know if you still have some control over your limbs.”

The words hung in the air as other people soon gathered around the group of three upon the ground. Margaret heard Edgar sniffling somewhere outside the circle and felt Harold, the priest, and his two brothers glaring down upon them from their seats. None of them had dismounted; instead, they surrounded the trio like a band of

highwaymen waiting to pounce on an unsuspecting victim. To Margaret’s dismay, her father’s eyelids did not flicker.

She studied Gerhard and watched the changing color of emotion move across his face—from confusion to concern, from fear to speculation, from suspicion to anger. When they both noticed the parting of her father’s lips, their hopes lifted. Together, she and Gerhard leaned in closer.

Her father’s eyes remained open but unfocused, and he whispered gently, more so to the air than to them. “No … feeling …my legs. My feet… cannot feel them… cannot move them… nothing there.”

Gerhard was about to respond but stopped when he saw Edward gather his breath once more. Unable to inhale deeply, he spoke in shallow exchanges. “Dizzy … since morn…could not get… legs…to keep hold … of the horse… chest feels … full… crushed.” He paused here for a lengthier break.

Margaret could feel her eyes welling up, her lashes wet with moisture.

“Cannot… take …. in … air.” With his gaze still focused at some point in the far distance, he whispered in a hushed tone, “Twas… foul… play.” Silence and he moved no more.

Margaret felt tears stinging her eyes. They burned her skin as they tumbled down her face until they left small, individual droplets of water on her father’s tunic. She watched as Gerhard placed his hand over Edward’s face, his fingers gently extending to close each eyelid.

Tiny bright-blue flowers with yellow centers formed a soft, decorative pillow where his sleeping head lay. Reminded of Jesus’ promise when he created these delicate blossoms, Margaret trusted that the Blessed Virgin would watch over her father’s soul. And she also knew that her father—like the flower itself—was urging her to “forget-me-not.”

Here’s the Blurb

Normandy, 1064

Celia Campion, a girl of humble background, finds herself caught in a web of intrigue when Duke William commands her to work as his spy, holding her younger sister hostage. Her mission: to sail across the sea to Wilton Abbey and convince Margaret, daughter of Edward the Exile, to take final vows rather than form a marriage alliance with the newly crowned king to the North, Malcolm III of Scotland. Preventing a union between the Saxons and Scots is critical to the success of the Duke’s plan to take England, and more importantly for Celia, it is the only way to keep her sister alive.

In this sweeping epic that spans the years before and after the Conquest, two women from opposite sides of the English Channel whisper across the chasm of time to tell their story of the tumultuous days that eventually changed the course of history. As they struggle to survive in a world marked by danger, loss, and betrayal, their lives intersect, and they soon come to realize they are both searching for the same thing–someone they can trust amidst the treachery that surrounds them.

Together, their voices form a narrative never before told.

Buy Link

Meet the Author

Award winning writer, Catherine Hughes, is a first-time author who, from her earliest years, immersed herself in reading. Historical fiction is her genre of choice, and her bookshelves are stocked with selections from ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Europe as well as those involving New England settlements and pioneer life in America. After double-majoring in English and business management on the undergraduate level, Catherine completed her Master’s degree in British literature at Drew University and then entered the classroom where she has been teaching American, British, and World Literature at the high school level for the last thirty years.

Aside from teaching and reading, Catherine can often be found outdoors, drawing beauty and inspiration from the world of nature. Taking the words of Thoreau to heart, “It is the marriage of the soul with nature that makes the intellect fruitful,” Catherine sets aside time every day to lace up her sneakers and run with her dog in pre-dawn or late afternoon hours on the beaches of Long Island. When her furry companion isn’t busy chasing seagulls or digging up remnants of dead fish, she soaks in the tranquility of the ocean setting, freeing her mind to tap into its deepest recesses where creativity and imagination preside.

In Silence Cries the Heart, Hughes’s first book, received the Gold Medal in Romance for the Feathered Quill 2024 Book of the Year contest, the Gold Medal for Fiction in the 2024 Literary Titan competition, and the 2024 International Impact Book Award for Historical Fiction. In addition, the Historical Fiction Company gave it a five star rating and a Silver Medal in the category of Historical Fiction Romance. The book was also featured in the February 2024 Issue 31 of the Historical Times magazine and was listed as one of the Best Historical Fiction Books of 2024 by the History Bards Podcast. Therein Lies the Pearl is her second venture into the world of historical fiction.

Connect with the Author

Posts

Stay up to date with the latest from the blog.