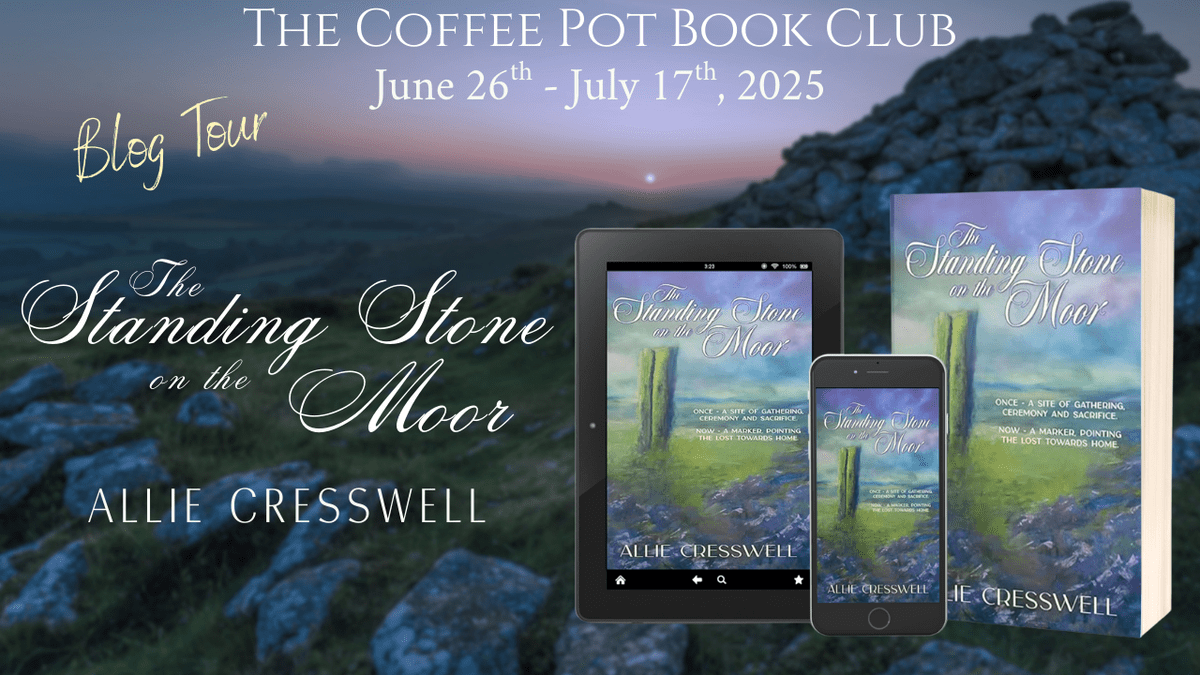

I’m delighted to welcome Allue Creswell and her new book, The Standing Stone on the Moor, with a blog post about the accurate representation of diversity in historical fiction.

The accurate representation of diversity in historical fiction – by Allie Creswell

In recent times I have been challenged to ensure that my historical novels accurately represent the diversity that would have existed in their eras, but which was often ignored by writers of the time. For instance, Jane Austen’s novels have no black or ethnic minority characters, neither are there any characters with disabilities of any kind. Perhaps Sanditon was an attempt to rectify this, with a spa town ready to “cure” and a character described as “mulatto”. Mrs Smith, in Persuasion is incapacitated in some way due to injury. It could be argued that Tom Bertram in Mansfield Park suffers a crisis in mental health as well as from alcoholism, but these examples are insignificant when we think of the casts of white, healthy, ambulant and neurotypical characters in her books.

While wishing very much to be accurately inclusive and to embrace differently-abled characters as well as ones of non-white heritage, I would not wish to fall into the trap of tokenism. It is Amory Balfour’s superlative and remarkable beauty—rather than his skin colour—which makes him the perfect foil for my veiled heroine Georgina in The Lady in the Veil. Olivia, a character with Down Syndrome in The Cottage on Winter Moss is pivotal to the plot because she is privy to the village’s secrets—and a bit of a gossip—not because she has Down Syndrome.

For The Standing Stone on the Moor I wanted to introduce a group of characters who would bring some sparkle and pizzazz to a remote, parochial and insular village in Yorkshire. I wanted to shake the inhabitants up, and I also wanted to challenge them, to provoke their bigotry, suspicion and superstition into life because I wanted—in an oblique, non-confrontational way—to equate the situation of today’s asylum seekers and refugees with those who came to the UK for succour in the mid-nineteenth century. My aim in this approach was to add as many facets to my theme—displacement—as possible, and it seemed to me that there could be no clearer illustration of it than the experience of people hounded from their homes and forced to establish themselves elsewhere.

The potato famine was at its peak in 1845, and thousands of Irish people made the trip to Britian in search of work and to escape the dreadful conditions at home. There was a kind of serendipity in this, in that the burgeoning industrial revolution in Britain had an insatiable requirement for workers in mills, factories, mines and to dig the canals—an activity which thousands of Irish undertook, giving rise to the characteristic designation of the “Irish navvy”.

Many British rural people had migrated to the towns for the improved wages these positions offered, but that left a deficit of labour in the countryside, which my Irish people seek to fill. The group is predominantly women and children. The few men in the group have conditions which ill-suit them to work in an industrial setting—one has asthma, another has suffered an amputation of the lower arm. They shear sheep and make hay, dig peat and move stones—anything at all that will pay. They get involved in the movement of contraband goods, and play shamelessly on their reputation for fortune-telling and mysticism, but this backfires on them. They establish themselves in a camp at a discreet distance from the village, next to an ancient standing stone. They bring their rich culture of music and dance, their entrepreneurship, their admirable work ethic, their predominantly Catholic religion and also of course their baggage—of suffering, loss and grief that prompted their journey, not to mention the trauma of that very displacement.

And this group of Irish people also brings Dónall, a young man with an intellectual disability.

My research into the ways people with intellectual disabilities were viewed and treated in the 19th century unearthed some dreadful facts. They were often labelled as “idiots” or “lunatics” and faced significant stigma and marginalization. They were frequently confined to institutions like workhouses and asylums, sometimes under harsh and inhumane conditions. These institutions, initially intended for a few hundred people, grew to house over 100,000 by the end of the century. At this time mental health treatment had not been developed and so conditions which we recognise and treat today as mental illnesses were considered signs of madness. Those displaying symptoms were locked away from society. So it was safe to assume that people rarely encountered those with intellectual disabilities, and my character Dónall would therefore likely be the target of stares, pointing fingers and worse.

Dónall had been deprived of oxygen at birth and though a strapping young man physically, aged in his early twenties, he has the intellectual age of a young child. Physically and sexually he is mature, but he lacks the mental scope to understand or control the natural urges of his body. This essential conflict feeds into the overarching theme of the book—displacement. Dónall is a boy in a man’s body, a child in a man’s world. He has adult compulsions of attraction towards Aoife, his cousin, but he also looks to her for the kind of reassurance and guidance a mother or older sister might provide.

Developing Dónall’s character was a delicate matter. I wanted him to be a character with a disability, rather than “a disabled character”, with a real role to play in the plot. I wanted to draw out the way the contradiction of his character affected him, to allow the reader to see his essential kindness and innocence but also his confusion, and the great passion in his soul.

Conn and Dónall lay in their makeshift beds beneath the wagon and watched the men depart on their clandestine business.

‘Where’re they going?’ Dónall asked.

‘They go to do some moonlight work,’ said Conn knowledgeably. ‘Poaching, perhaps.’

Dónall creased his brow. ‘Rabbits?’

‘Deer, more likely, or pheasant. Go to sleep, Dónall. We are to work alongside the men tomorrow.’

‘There is no market,’ said Dónall, yawning. And then, after such a pause that Conn thought he must be asleep, ‘Your mother has a baby in her belly.’

Conn sighed. ‘Yes.

‘How did it get there?’

Conn turned his head. Dónall’s pale eyes shone in the darkness. ‘I suppose my father put it there. Do you not know about such things?’

Dónall shook his head. His face creased this way and that as he tried to get his thoughts into a shape he could manage but in the end he only said, ‘Aoife would not say.’

‘You have seen the dogs do it often enough,’ said Conn. ‘It is like that, I suppose, but Father Fearghal says that people must wait until they are married, or it is a sin. I would not trouble yourself about it.’

‘Aoife is not married,’ Dónall said, partly comforted, party distressed, partly fascinated

‘Not yet, anyway.’ Conn yawned. ‘Good night, Dónall.’ He turned on his side, but Dónall rose up onto one elbow.

‘Aoife can’t … No. She mustn’t …’

Conn turned back to look at him. ‘Mustn’t get married?’

‘N… no.’ Dónall swallowed thickly. ‘And there mustn’t be … a baby,’ he said.

Conn settled himself back down. ‘I know what you mean. There isn’t enough to go around as it is. But babies do come once the vows are exchanged. They do not seem to be able to stop themselves.’

Dónall said, ‘My mother … she died …’

Conn sighed. ‘Yes, I know, Dónall. It sometimes happens. And sometimes the baby dies. Father Fearghal says it is God’s will. Is that why you don’t want Aoife to have a baby? Because you worry that she will die?’

Dónall thought about it for a while. ‘No,’ he said at last. ‘It is because … because … I do not want to share.’

When Dónall’s impulses get the better of him, he commits a crime for which there will be serious consequences. At best, a life in an asylum. At worst, hanging. It is not his disability per se which is the catalyst, but its manifestation within his character and the situation into which I placed him. Dónall’s perilous situation forces his Irish friends and Beth, my main character, to attempt a daring and dangerous trip across the moors in the dead of night, dodging the mounted guard.

One of the quite beautiful things that emerged as I wrote Dónall’s character was the way his Irish family love and care for him, and the ways they allow him to contribute to their communal well-being. At mealtimes he is placed among the children, where he soothes tiredness and squabbling with a timely tickle or cuddle. During the day he works alongside the men, having twice the strength of some, moving stones. His strengths are celebrated, his weaknesses compensated for and never ridiculed or criticised.

Dónall knuckled the tears from his eyes and leaned against Ruairi as a child would have done after being separated for even a few moments from a beloved parent’s affection, and allowed himself to be soothed and comforted before being led towards the circle and seated on the upturned barrel that would normally have been Ruairi’s own preserve.

‘There now,’ said Ruairi. ‘You shall have a man’s seat and a man’s portion of supper and a glass of grog to wash it down with since you have done a man’s work today.’

Dónall nodded and tried a watery smile.

In developing Dónall’s character I was very lucky to have the support and incredible expertise of Deirdre O’Grady (https://www.abilitywise.ie/) who is my sensitivity reader. Deirdre has a H-Dip in Facilitating Inclusion, diplomas in psychology and disability studies and years of experience of raising awareness of the needs of those with disabilities within the workplace and the community. She is an ambassador for diversity, equality and inclusion who is also an expert in mental health, addiction and domestic abuse.

Here’s the blurb

Yorkshire, 1845.

Folklore whispers that they used to burn witches at the standing stone on the moor. When the wind is easterly, it wails a strange lament. History declares it was placed as a marker, visible for miles—a signpost for the lost, directing them towards home.

Forced from their homeland by the potato famine, a group of itinerant Irish refugees sets up camp by the stone. They are met with suspicion by the locals, branded as ‘thieves and ne’er-do-wells.’ Only Beth Harlish takes pity on them, and finds herself instantly attracted to Ruairi, their charismatic leader.

Beth is the steward of nearby manor Tall Chimneys—a thankless task as the owners never visit. An educated young woman, Beth feels restless, like she doesn’t belong. But somehow ‘home’—the old house, the moor and the standing stone—exerts an uncanny magnetism. Thus Ruairi’s great sacrifice—deserting his beloved Irish homestead to save his family—resonates strongly with her.

Could she leave her home to be with him? Will he even ask her to?

As she struggles with her feelings, things take a sinister turn. The peaceable village is threatened by shrouded men crossing the moor at night, smuggling contraband from the coast. Worse, the exotic dancing of a sultry-eyed Irishwoman has local men in a feverish grip. Their womenfolk begin to mutter about spells and witchcraft. And burning.

The Irish refugees must move on, and quickly. Will Beth choose an itinerant life with Ruairi? Or will the power of ‘home’ be too strong?

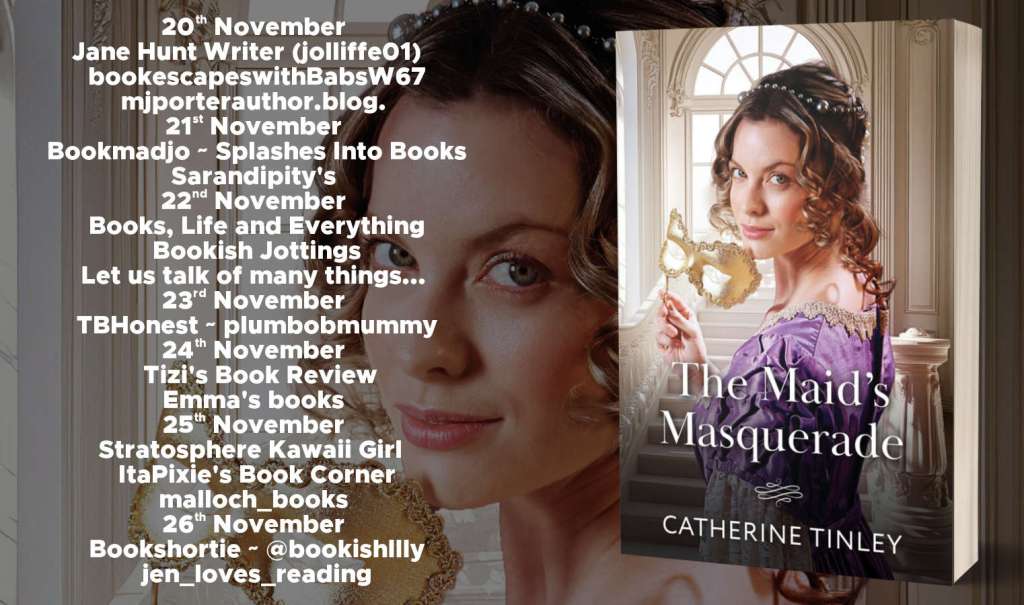

Buy Link

Universal Link:

Author’s Website:

Meet the Author

Allie has been writing fiction since she could hold a pencil. She has a BA and an MA in English Literature, specialising in the classics of the nineteenth century.

She has been a print-buyer, a pub landlady, a bookkeeper and the owner of a group of boutique holiday cottage but nowadays she writes full time.

She has two grownup children, five grandchildren and two cockapoos but just one husband, Tim. They live in the remote northwest of the UK.

The Standing Stone on the Moor is her sixteenth novel.

Connect with the Author