Penda of Mercia

Penda of Mercia is famous for many things, including killing two Northumbrian kings throughout his life. He’s also famous for being a pagan at a time when Roman Christianity was asserting itself from the southern kingdom of Kent. But who was he?

Who was Penda of Mercia?

Penda’s origins are unclear. We don’t know when he was born or where he came from, although it must be assumed he was a member of a family from which the growing kingdom of Mercia might look for its kings. He’s often associated with the subkingdom of the Hwicce, centered around Gloucester. The later source, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written at least two hundred and fifty years after his life records,

626 ‘And Penda had the kingdom for 30 years; and he was 50 years old when he succeeded to the kingdom.’ ASC A p24

626 ‘And here Penda succeeded to the kingdom, and ruled 30 years.’ ASC E p25

Knowing, as we do, that he died in 655, this would have made Penda over eighty years old at his death, a fact that is much debated. Was his age just part of the allure of the legend? A mighty pagan warrior, fighting well into his eighties? Sadly, we may never know the truth of that, but it is disputed, and there are intricate problems with the sources that boggle the brain.

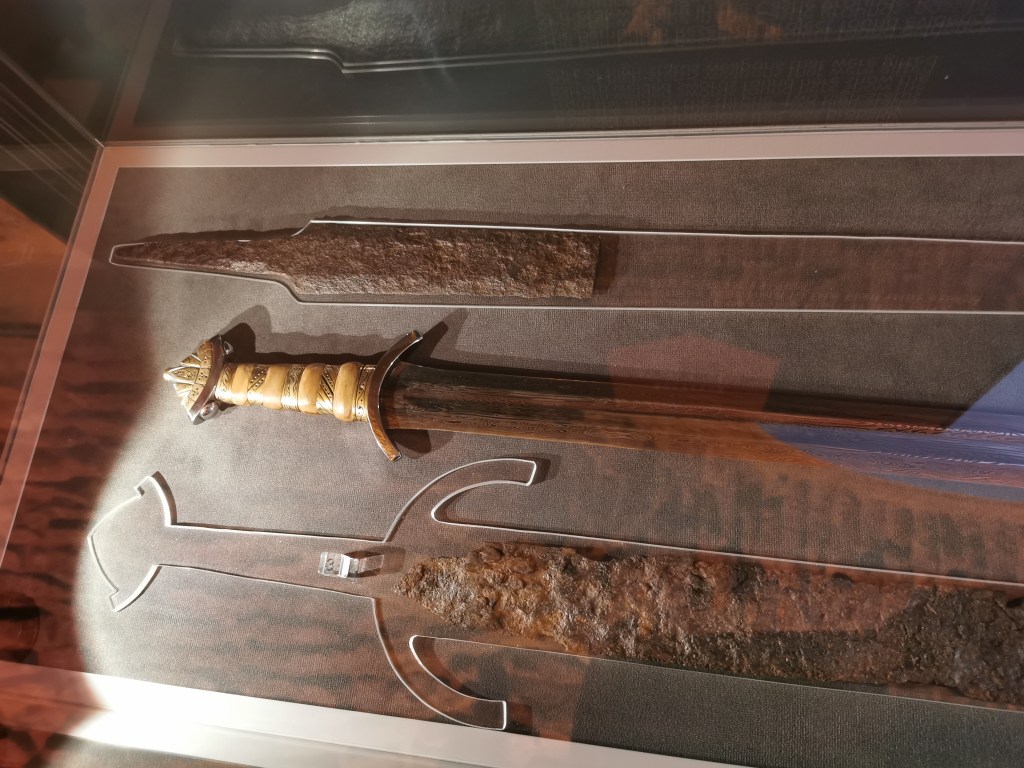

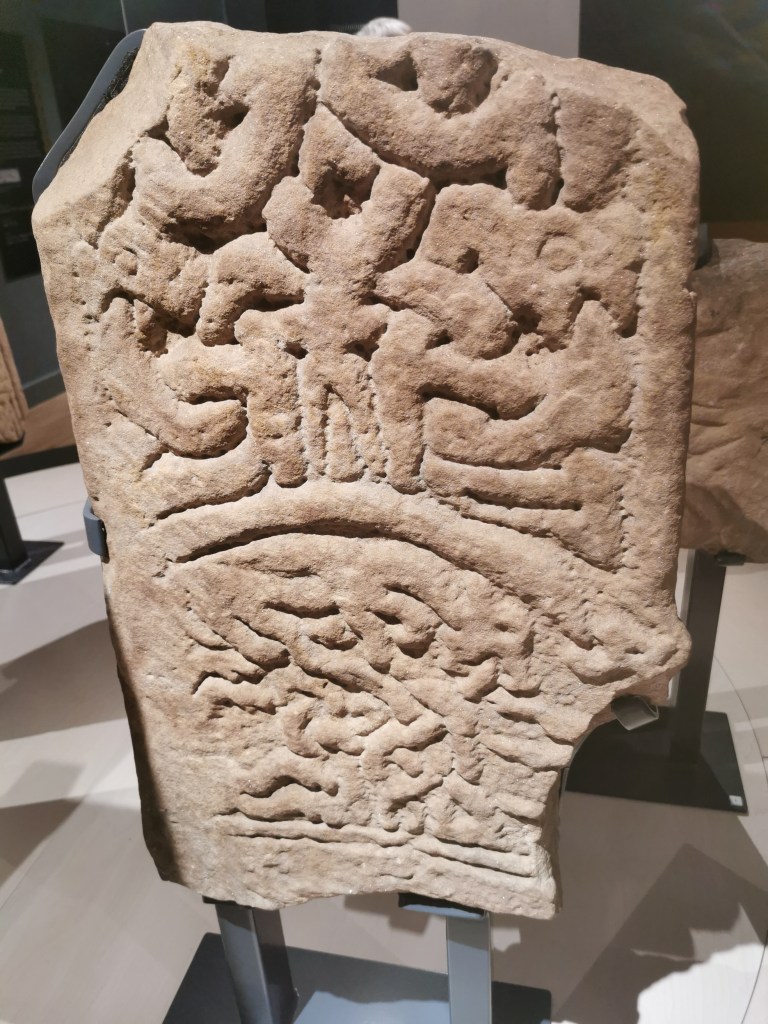

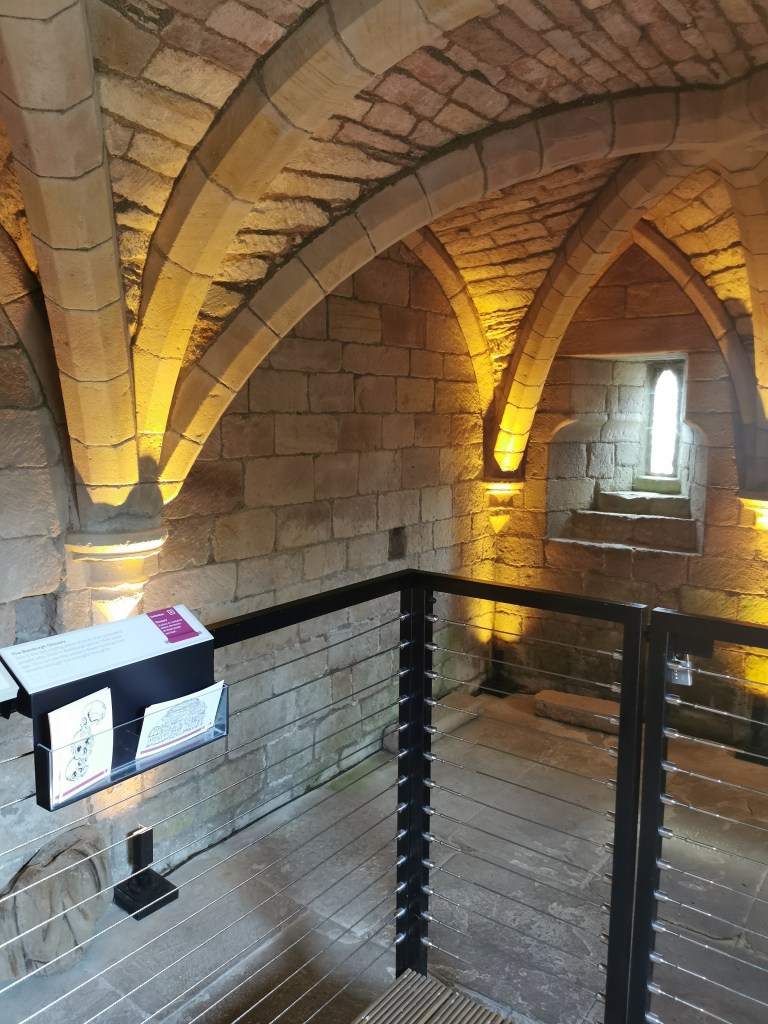

Hædfeld, Maserfeld and Winwæd

Suffice it to say, we don’t know Penda’s age or origins clearly, but we do know that he was involved in three very famous battles throughout the middle years of the seventh century, that at Hædfeld in 632/33 fought somewhere close to the River Don, in which King Edwin of Northumbria was killed. That of Maserfeld, in 641/2 in which King Oswald of Northumbria was killed, close to Oswestry, not far from today’s Welsh border. And Penda’s final battle, that of Winwæd in 655 in which he was killed while fighting in the north, perhaps close to Leeds. While these are the battles we know a great deal about, thanks to the writings of Bede and his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a Northumbrian monk, with an interest in Northumbria’s religious conversion, who completed his work in 731, Penda was a warrior through and through. He fought the kingdoms to the south, the West Saxons, or Wessex as we might know it. He fought in the kingdom of the East Angles. He allied with Welsh kings. He meddled in affairs in Northumbria, and had he not died in 655, it is possible that Northumbria’s Golden Age would have ended much sooner than it did. His son married a Northumbrian princess. His daughter married a Northumbrian prince. Penda was either brokering an alliance with Northumbria or perhaps using marriage as a means of assimilating a kingdom that he was clear to overrun.

Bede

Our narrator of Penda’s reign, is sadly a Christian monk writing up to seventy years after his death. His commentary is biased, and his story is focused on the triumph of religion and Northumbria, probably in that order. And yet, as Bede’s work was coming to its conclusion, even he understood that the Golden Age of Northumbria was coming to an end. A later king, Æthelbald, related not to Penda, but to his brother, Eowa, killed at the battle of Maserfeld, although whether fighting beside his brother or for the enemy is unknown, was the force in Saxon England at the time. How those words must have burned to write when Bede couldn’t skewer the contemporary narrative as he might have liked.

But while Penda’s reign is so closely tied to the words of Bede, our only real source from the period in Saxon England, although there are sources that exist from Wales and Ireland, Penda’s achievements aren’t to be ignored.

Penda’s reputation

Recent historians cast Penda in a complimentary light. D.P. Kirby calls him ‘without question the most powerful Mercian ruler so far to have emerged in the Midlands.’ Frank Stenton has gone further, ‘the most formidable king in England.’ While N J Higham accords him ‘a pre-eminent reputation as a god-protected, warrior king.’ These aren’t hastily given words from men who’ve studied Saxon England to a much greater degree than I have. Penda and his reputation need a thorough reassessment.

After his death, his children ruled after him, but in time, it was to his brother’s side of the family that later kings claimed their descent, both King Æthelbald and King Offa of the eighth-century Mercian supremacy are said to have descended from Eowa.

Check out the Gods and Kings page for more information.