Who was Ealdorman Leofwine?

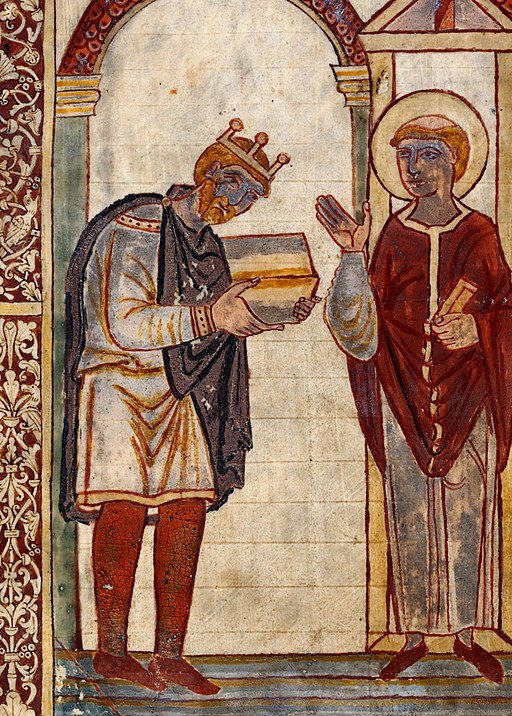

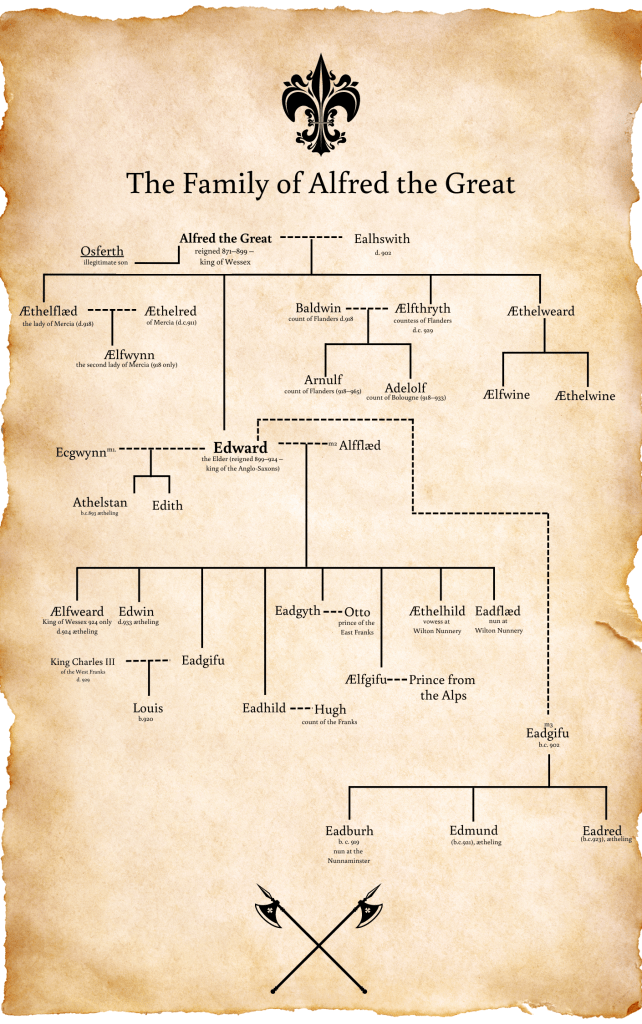

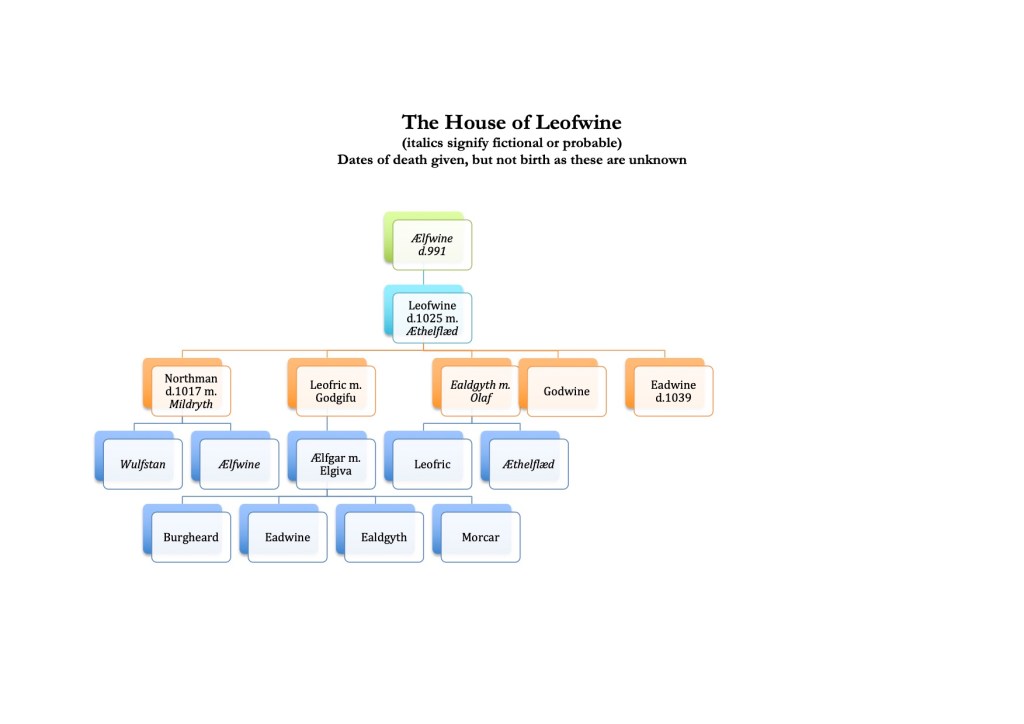

Ealdorman Leofwine , was the ealdorman of the Hwicce (c.994-1023), one of the ancient tribal regions in Mercia, which was a part of England, at the time the story begins. It is possible he may have been related to Ælfwine, who is named, and dies at the Battle of Maldon (more below).

Ealdorman Leofwine and his descendants, who would hold positions of power until the Norman Conquest of 1066, are a unique family in this tumultuous period. No other family, apart from the ruling family of Wessex (and even then there was a minor hiccup caused by those pesky Danish kings) held a position of such power and influence and for such a long period of time, as far as is currently known. The position of ealdorman was not hereditary. It was a position in the gift of the king, and Saxon kings ruled with a varying number of ealdormen. To understand Leofwine’s significance, it’s important to understand this. Unlike an earl – a term we are all perhaps far more familiar with – but specifically a medieval earl in this regard – that position was both more often than not hereditary AND meant that the person involved ‘owned’ significant properties in the area they were earls over. This is not how the ealdormanic system worked in Saxon England, as it’s currently understood.

It is difficult to track many of the ealdormanic families of this period, and the previous century, but there are a few notable individuals, all who bucked the usual trend, which no doubt accounts for why we know who they are.

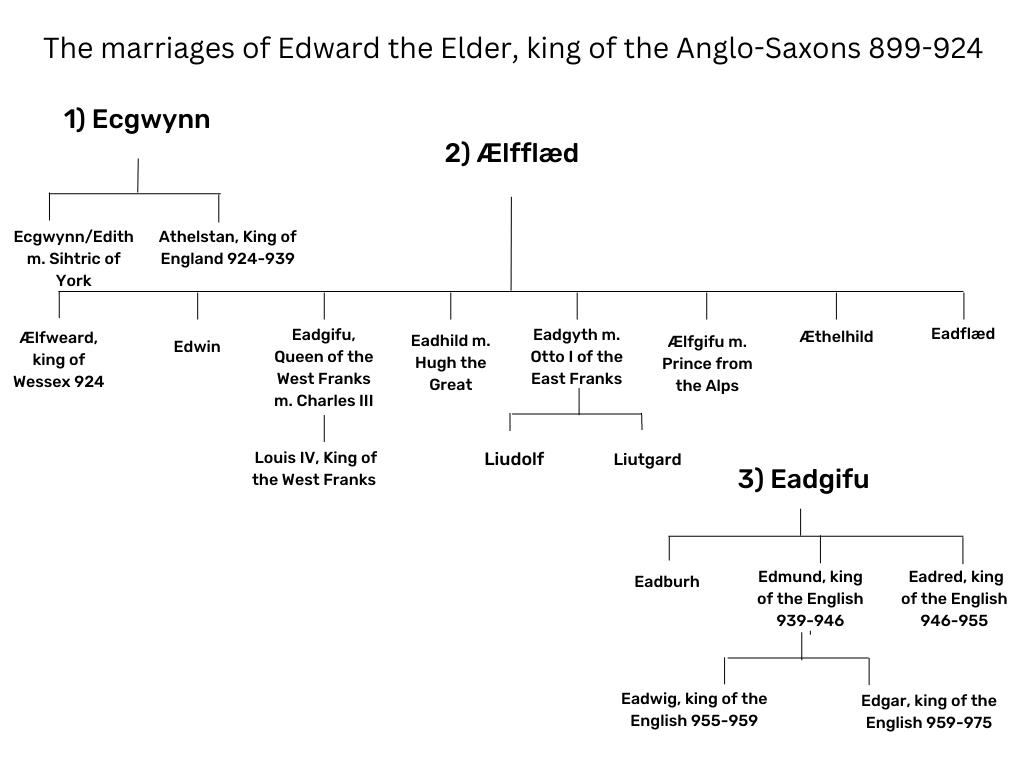

Perhaps most well-known is Ealdorman Athelstan Half-King, who was the ealdorman of East Anglia from about 934 to 955/6 when he fell from favour at court during the reign of King Eadwig and retired to Glastonbury Abbey. Before he did so, he ensured that his son, Æthelwald, was elevated to the position of ealdorman in his place. This was most unusual, but then, he came from a powerful family, fiercely loyal to the ruling House of Wessex, if not actually a member of them. Athelstan Half-King is believed to have been the son of Ealdorman Æthelfrith, a Mercian ealdorman when Lady Æthelflæd was the Lady of Mercia. Athelstan was one of four brothers. His older brother seems to have either briefly retained the ealdordom after their father’s death in Mercia, or been accorded it a few years later, but when he died, Athelstan Half-King didn’t become ealdorman of Mercia in his place. No, he remained in East Anglia while his two brothers, Eahric and Æthelwald, held ealdordoms in Wessex (Eahric) and Kent (Æthelwald). They didn’t become the ealdorman of Mercia either. The ealdordom passed to a different individual.

When Ealdorman Æthelwald of the East Angles died a few short years later (Athelstan Half-King’s son), his place was taken by Ealdorman Æthelwine, the youngest of Athelstan Half-King’s children. But, the family failed to hold on to the position, despite Ealdorman Æthelwine being married three times, and fathering three sons, one of whom died at the battle of Assandun in 1016. The next to hold the ealdordom of the East Angles after the death of Æthelwine was Leofsige, who was the ealdorman until he fell foul of the king in 1002. In the early 1000s Ulfcytel emerges and may have been married to one of the king’s daughters, but is never officially accorded the title of ealdorman. You can read about Ealdorman Athelstan Half-King in The Brunanburh Series.

Another famous ealdorman was Byrhtnoth of Essex, who died at the Battle of Maldon in 991. But Byrhtnoth was not the son of the previous ealdorman, and indeed, he married the daughter of a very wealthy man and in turn was raised to an ealdordom in Essex at exactly the same time that Ealdorman Athelstan Half-King was being forced to retire from his position in East Anglia. (Byrhtnoth’s wife’s sister had briefly been married to King Edmund (939-946, before his murder). While there are some arguments that Byrhtnoth was from a well regarded family, his appointment was not because of an hereditary claim. It’s known that he was father to a daughter, but not to a son. As such his family did not retain the ealdordom on his death. Indeed, it seems as though Essex and the East Anglian earlordoms were united for a time under Leofsige.

The argument has been put forth that the position of ealdorman may have come with properties that were the king’s to gift to the individual to enable them to carry out their duties in a particular area. The Saxons had a number of types of land tenure, bookland, was land of which the ‘owners’ held the ‘book’ or ‘the title deed.’ (There are some wonderful charters where landed people had to ask for the king to reissue a charter as theirs was lost, often in a fire. There is a wonderful example where King Edgar has to reissue a charter for his grandmother, as he’d lost it while it was in his care). Other land tenure was ‘loan land,’ that is land that could be loaned out, often for a set number of ‘lives.’ Ealdormen might then have held bookland that was hereditary, and not in the area they were ealdorman of, and loan land that was in the king’s to gift to them within the area that they were the appointed ealdorman.

Many will be familiar with the family of Earl Godwine and his sons (thanks to the influence of the Danes, the term ealdorman was replaced by earl, which was the anglicised version of jarl). Much work has been done on the land that the Godwine family held when the great Domesday survey was undertaken during the reign of William the Conqueror. It will quickly become apparent that while they had areas where they held a great deal of land, these were not necessarily the areas over which first Godwin and then his sons Tostig, Harold, Gyrth, Leofwine and Sweyn held the position of earl. Most notably, Tostig was earl of Northumbria from 1055-1065, and yet the family had almost no landed possessions there.

And this is where we return to Ealdorman Leofwine and his family. While everyone knows about Earl Godwine and his sons, they didn’t hold their position for as long as Ealdorman Leofwine and his family. Earl Godwine is first named as an earl in charter S951 dated to 1018. By that period, Leofwine of the Twice had already held a position of importance since 994. The families of both men would converge as the events of 1066 drew nearer, and indeed, Godwine’s son, Harold, was married to Ealdorman Leofwine’s great-granddaughter when he was briefly king of England.

When Ealdorman Leofwine died, his son, Leofric, didn’t become ealdorman in his place. Leofric was a sheriff during the period between his father’s death and his own appointment. And indeed, Leofric’s son, Ælfgar was elevated to an earldom before his father’s death, and so was not initially the earl of Mercia. However, on this occasion, and because of a political situation that was rife with intrigue, Ælfgar did become the earl of Mercia after his father’s death, and after Ælfgar’s death, his young son also took the earldom of Mercia. The family survived the events of 1066, but they didn’t retain their hold on the earldom. The House of Leofwine were a family to not only rival that of Earl Godwine’s, as far as it’s known, but they were also the ONLY family to retain a position as an ealdorman/earl for over seventy years. And yet, very few know about them, and indeed, in many non-fiction books, they’re not even mentioned. And that was the perfect opportunity for me to write about the fabulous family, largely inspired by a non-fiction book, The Earls of Mercia: Lordship and Power in Late Anglo-Saxon England by Stephen Baxter.