Having written more books than I probably should about the Saxon kingdom of Mercia, and with more planned, I’ve somewhat belatedly realised I’ve never explained what Mercia actually was. I’m going to correct that now.

Having grown up within the ancient kingdom of Mercia, still referenced today in such titles as the West Mercia Police, I feel I’ve always been aware of the heritage of the Midlands of England. But that doesn’t mean everyone else is.

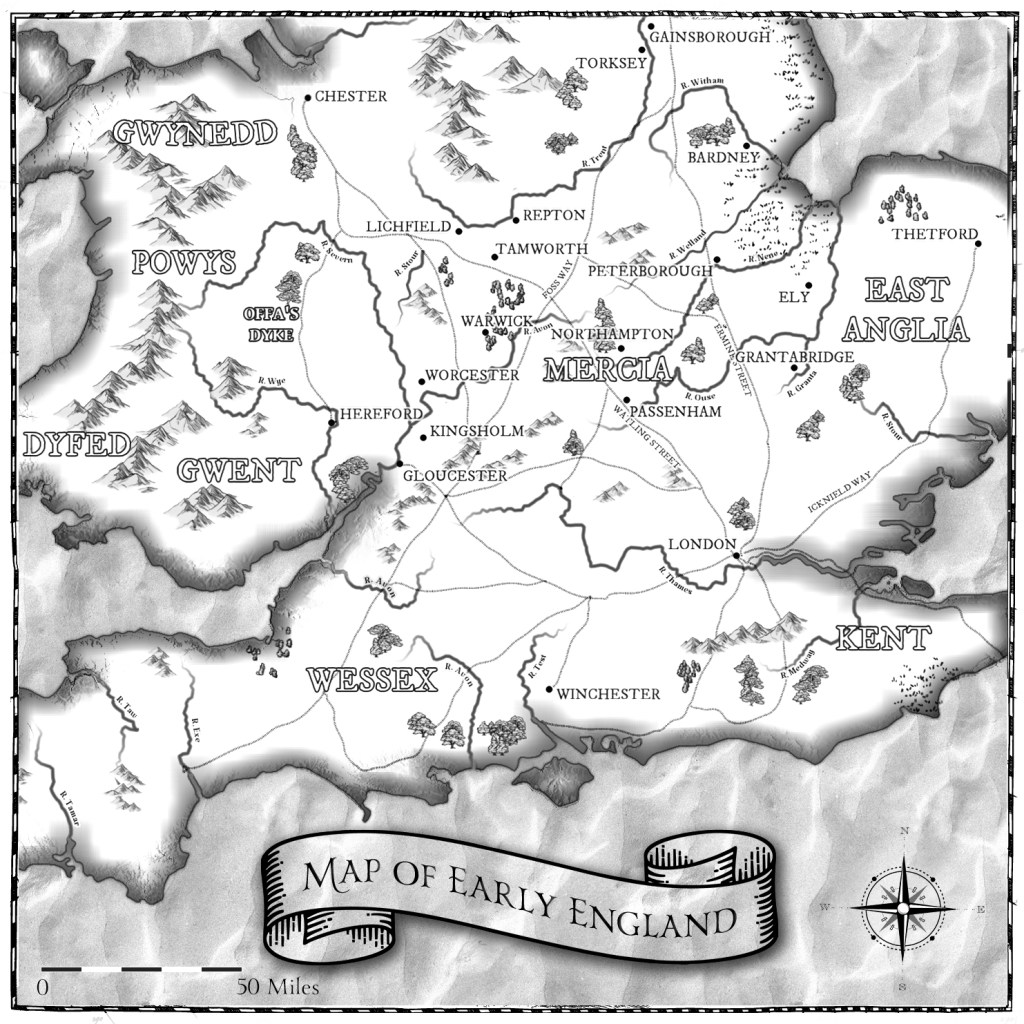

Where was Mercia?

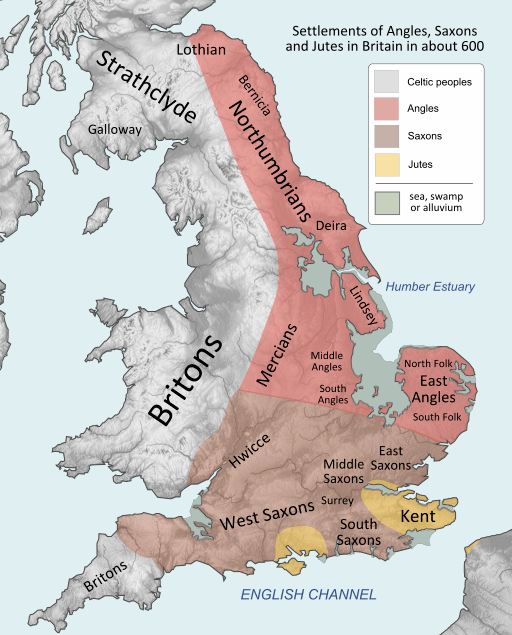

Simply put, the kingdom of Mercia, in existence from c.550 to about c.925 (and then continuing as an ealdordom, and then earldom) covered the area in the English Midlands, perhaps most easily described as the area north of the River Thames, and south of the Humber Estuary – indeed, nerdy historians, and Bede, call the area the kingdom of the Southumbrians, in contrast to the kingdom of the Northumbrians – do you see what Bede did there?

While it was not always that contained, and while it was not always that large, Mercia was essentially a land-locked state (if you ignore all the rivers that gave easy access to the sea), in the heartland of what we now know as England.

What was Mercia?

Mercia was one of the Heptarchy—the seven ancient kingdoms that came to dominate Saxon England – Mercia, Wessex (West Saxons), the East Angles, Essex (East Saxons), Sussex (South Saxons) and Kent.

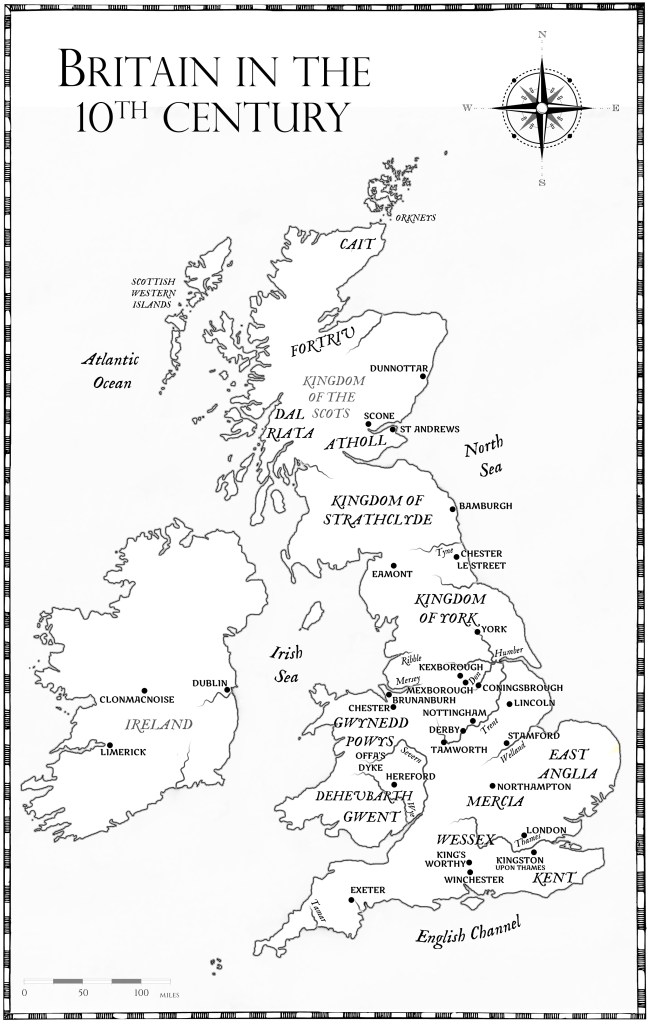

In time, it would be one of only four to survive the infighting and amalgamation of the smaller kingdoms, alongside Northumbria, the kingdom of the East Angles, Mercia, and Wessex (the West Saxons).

The End of Mercia?

Subsequently, it has traditionally been said to have been subsumed by the kingdom of Wessex, which then grew to become all of ‘England’ as we know it.

This argument is subject to some current debate, especially as the king credited with doing this, Athelstan, the first and only of his name, might well have been born into the West Saxon dynasty but was potentially raised in Mercia, by his aunt, Lady Æthelflæd, and was, indeed, declared king of Mercia on the death of his father, King Edward the Elder in July 924, and only subsequently became king of Wessex, and eventually, king of all England.

Mercia’s kings

But, before all that, Mercia had its own kings. One of the earliest, and perhaps most well-known, was Penda, in the mid-7th century, the alleged last great pagan king. (Penda features in my Gods and Kings trilogy). Throughout the eighth century, Mercia had two more powerful kings, Æthelbald and Offa (of Offa’s Dyke fame), and then the ninth century saw kings Wiglaf and Coelwulf II (both of whom feature as characters in my later series, The Eagle of Mercia Chronicles and the Mercian Ninth Century), before the events of the last 800s saw Æthelflæd, one of the most famous rulers, leading the kingdom against the Viking raiders.

The Earldom of Mercia

And even when the kingdom itself ceased to exist, it persisted in the ealdordom and earldom of Mercia, (sometimes subdivided further), and I’ve also written about the House of Leofwine, who were ealdormen and then earls of Mercia throughout the final century of Saxon England, a steadfast family not outmatched by any other family, even the ruling line of the House of Wessex.

In fact, Mercia, as I said above, persists as an idea today even though it’s been many years since the end of Saxon England. And indeed, my two Erdington Mysteries, are also set in a place that would have been part of Mercia a thousand years before:) (I may be a little bit obsessed with the place).