Sometimes, it seems to me, that fiction and non-fiction authors of the Saxon era believe the stories they’re told about Saxon England which are actually the result of much later sources. This of course, means that the later stories, more often than not the work of Norman pseudo-historians writing in the 1100s and later, grow in popularity while fewer people understand that the stories are not only not contemporary, they might have been written down hundreds of years after the events they allegedly describe and discuss.

I make no bones of the fact that understanding the sources of the Saxon period is complex and difficult. Much of it depends on what a scholar, or a reader, might take as the ‘level of credibility.’ Some people will take saints lives at face value, others will not. Some will find value in poems and some will not. Some, and I include myself in this, will misconstrue the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and realise they were reading it all wrong.

There are really very few sources available for the modern reader. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is very well known, but perhaps not the bones of how it was constructed (please see Pauline Stafford’s book After Alfred for a comprehensive, and frankly, mind-blowing discussion). The words of Bede are often cited. There are charters, wills, legal documents, some poetry and saints lives, as mentioned above. This is not a huge amount to build a narrative upon, and yet historians have done this for many years – to some the increasing amount of archaeological information (often contradictory) is an annoyance, but for others, it has made the merits of the surviving written word more questionable. We should be asking, ‘why do we know what we know,’ as opposed to lapping it up and assuming its authenticity.

Another problem is the scarcity of the surviving documents, and the fact that very, very few of them survive in contemporary formats. With the best will in the world, what is copied isn’t always correct and equally, the temptation to embellish mustn’t be ignored, and that’s before we return to the heart of the problem. What was written was written for a purpose. As today, everything contains bias, it exhibits their intentions (Bede wrote an ecclesiastical history – the clue is in the name), while the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle was a Wessex based endeavour, at least in the beginning. The surviving nine recensions changed hands on more than one occasion, and the bias subsequently changed with it. We imagine monks labouriously copying out the texts, letter by letter, but what if the words were written by female religious? Or not by the religious at all? What if they were a state-sponsored endeavour to present their patron in the best possible light? Who was that patron? Was that patron always the same one? We don’t, it appears, have the ‘original’ version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. The versions available to us are all copies – written out at various points from the tenth to the twelfth century, and then again, heavily annotated during the Tudor era.

And this is merely another step along the way. Few can read these precious sources in their original format or even in their original language. We rely on translations, which allow a fresh wave of bias, and also, understanding. Our world is different to the world the Saxons lived within. They had different contexts for some words. While researching for my non-fiction book, I was amazed to discover the work of Sarah Foot and the Veiled Women of England, and her assertion that the word ‘nonne‘ might not have meant a cloistered nun, as we assume from the similarity of the two words.

We don’t know far more than we do know. There is a temptation to ‘plug’ the gaps with any available knowledge. And that’s not a problem, providing the author confirms it is fiction, not non-fiction. I write fiction, but I know the non-fiction the stories are built upon (hopefully). I write extensive historical notes for all of my books. I play with the possibilities, and purposefully reinterpret the ‘gaps’ but I don’t pretend that what I write is factual.

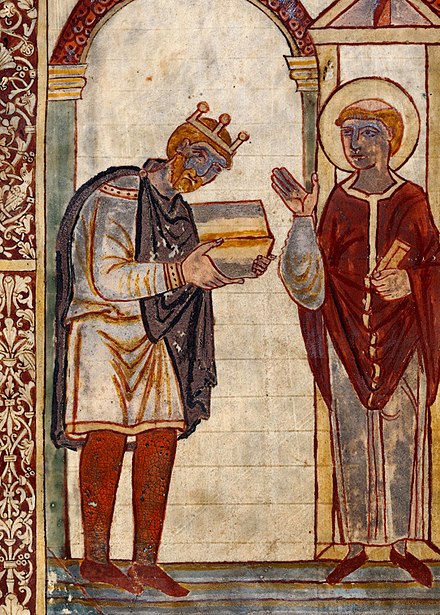

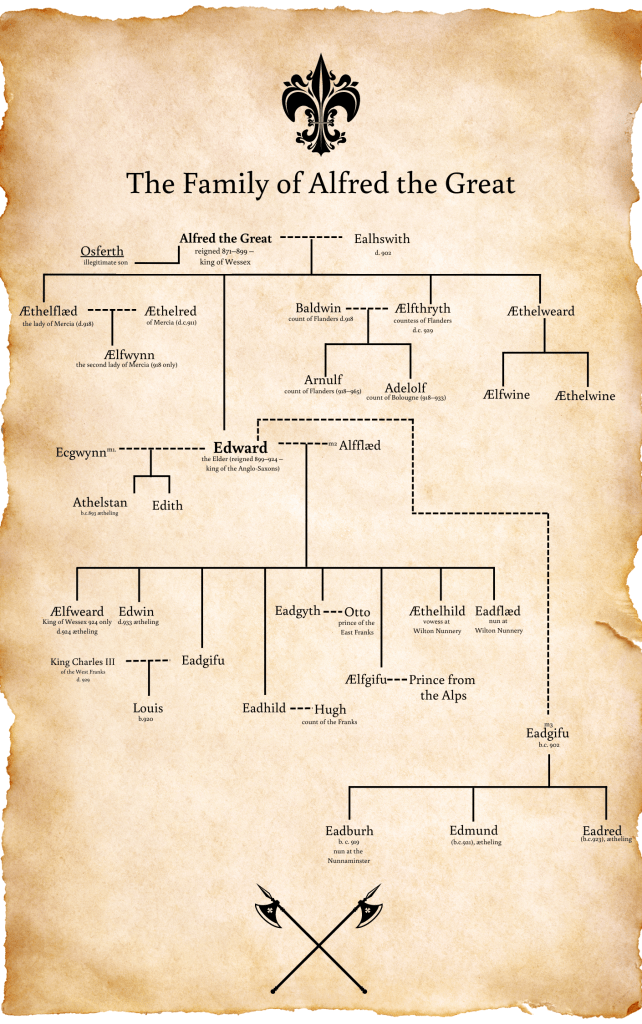

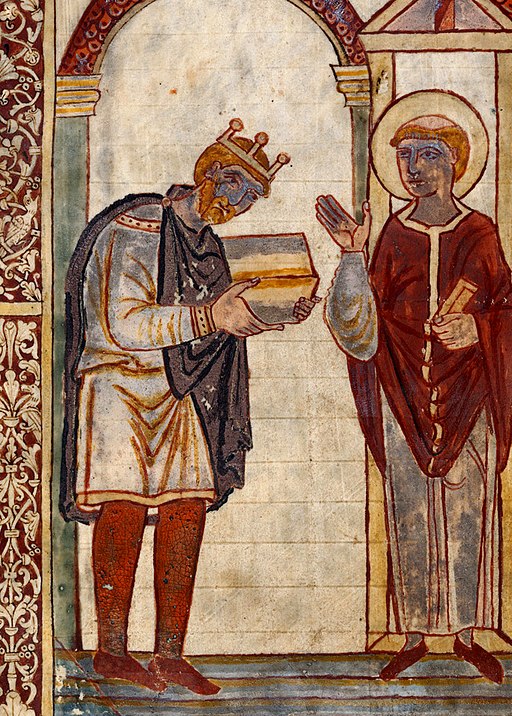

We have almost no images of anyone who lived in Saxon England. There are contemporary images of King Athelstan and his nephew, King Edgar. I can’t think of a single contemporary image of a woman. The Bayeuax Tapestry dates to after the end of Saxon England. We might have something which was held, or commissioned by a Saxon woman, and a queen, if the embroideries found in St Cuthbert’s tomb were indeed made by Lady Ælflæd, the second wife of King Edward the Elder.

We do have coins, more often than not from archaeological or metal-detecting finds. They do allow us a tangible hold on this part of history, and increasingly are adding to the need to rewrite the written words that have survived. We also have increasing archaeological finds, but again, and as no expert in archaeology, there is also a thin line. Archaeologists often set out to ‘find’ something. What they find often isn’t that ‘thing’ but in the past, the temptation to present only limited information has allowed certain narratives to stand, which are only now being understood, just as with increasing study on the written sources.

When writing about Saxon England, we must be wary of all of these things – we need to be aware that very rarely is something what we expect it to be, and equally, we must remember that the people of Saxon England were just that, people. They would have been irrational, selfish, violent, horrible, brutal, honest, religious, fervent, foolish, intelligent or not.

And so, writing Saxon England is far from a simple task. It is very rare to be able to categorically state that something is ‘wrong’. It is even rarer to be able to categorically state that something is ‘correct.’ The work of a fiction writer might be easier than that of a non-fiction writer, but the fiction writer has to recreate people as well as a coherent narrative, and there are always people who will be happy to argue with those interpretations. And that is all they are, interpretations – but so, if non-fiction writers are honest enough to admit – is much of their work as well.

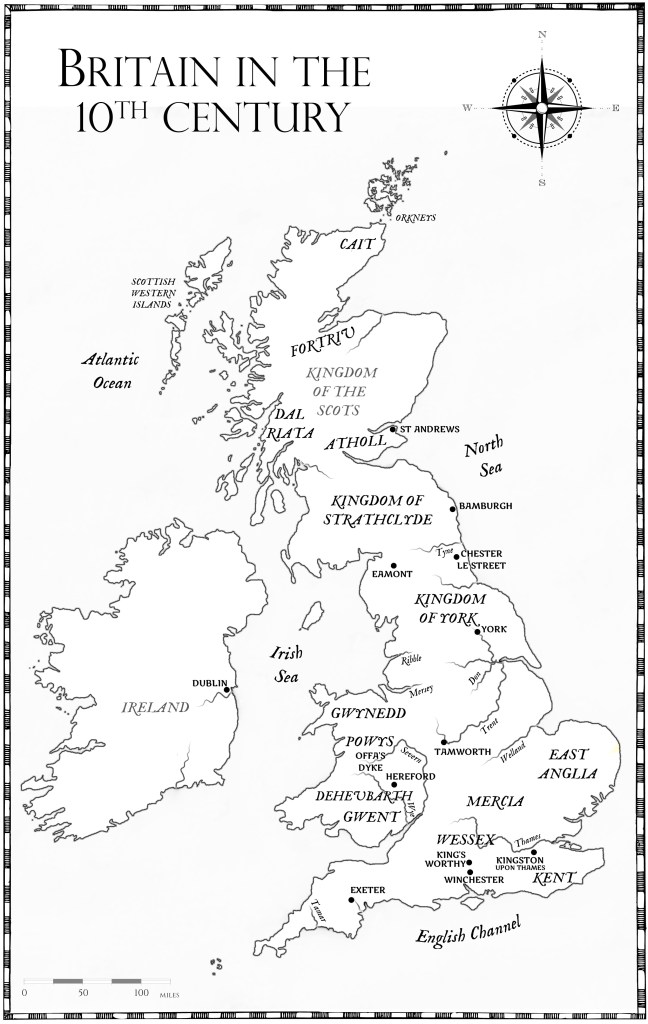

(I’ve not even discussed the problems of trying to write a coherent piece on the history of the British Isles at this time – contending with Old Norse, Old Irish, Old English, Old Welsh, Latin and no doubt, other languages that I’ve failed to mention).

That said, the era is fascinating. It’s worth investing in it, and taking the time to understand the complexities.

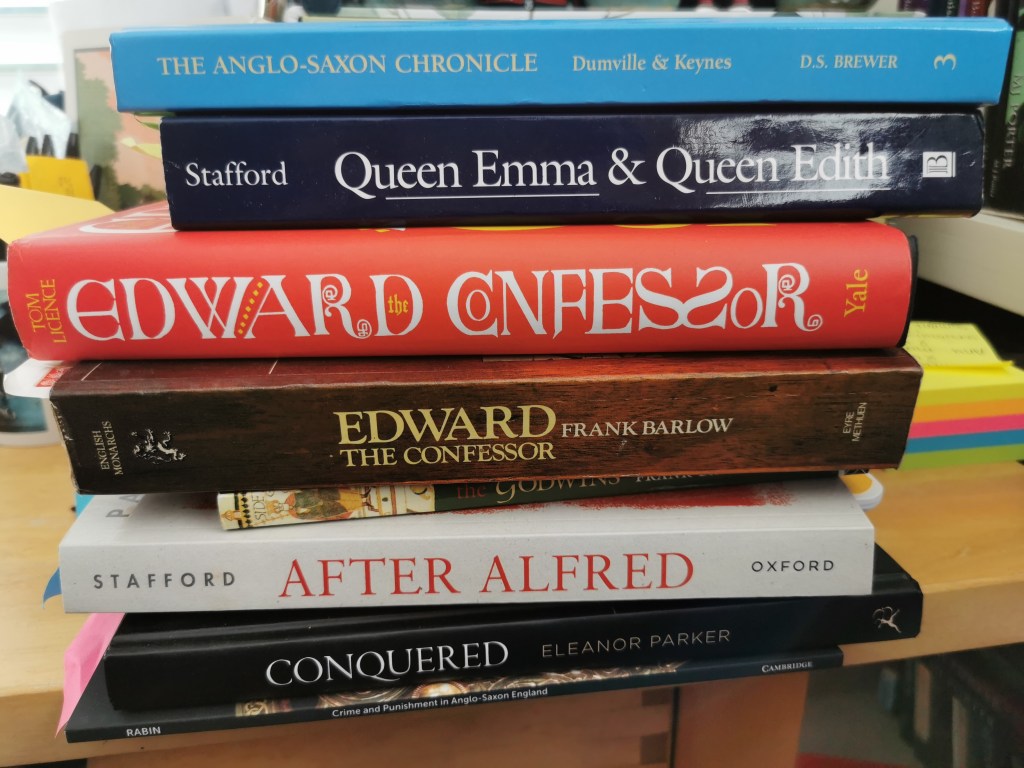

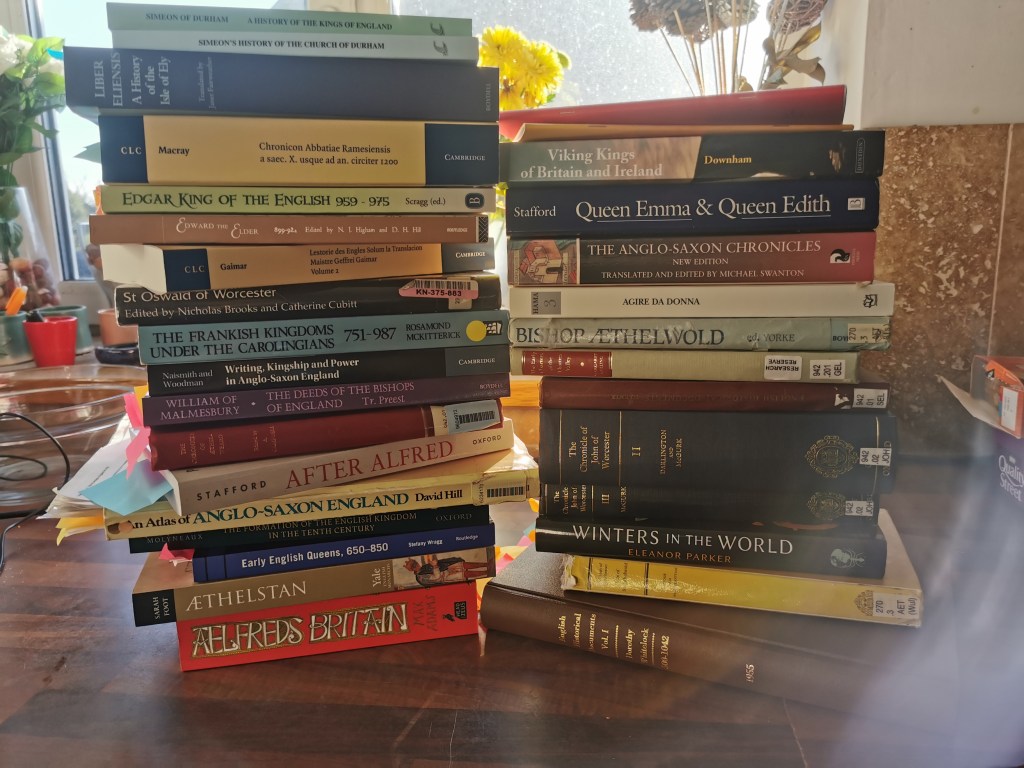

Looking to read about Saxon England? Here are some of the primary and secondary works that I highly recommend.

PRIMARY SOURCES

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles – translated and edited by Michael Swanton

English Historical Documents Vol 1 500-1042 – Dorothy Whitelock (a very expensive resource – perhaps best found in a library or online)

English Historical Documents Vol 2 1042-1189 – David C Douglas (as above. I was lucky to find some reasonably inexpensive copies but it took years)

An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon England – David Hill (It took me years but I eventually found a copy on Abebooks that didn’t break the bank)

The Electronic Sawyer – online catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters – an amazing resource once you feel confident to explore the primary sources. Used to be part of the KEMBLE online resource but this seems to have disappeared, which is a great shame.

The Prospography of Anglo Saxon England – this is a new one for me, but I wanted to share as it looks like it’s going to be extremely useful.

https://oepoetryfacsimile.org – Old English poetry collection, showing different translations, and reprints – fascinating – and revealing I’m not the only one with these concerns:)

SECONDARY SOURCES

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms by Claire Breay and Joanna Story

The First Kingdom by Max Adams

Aelfred’s Britain by Max Adams

After Alfred, Anglo-Saxon Chronicles and Chroniclers 900-1150 by Pauline Stafford, an absolute must to understand one of the most important sources for the period.

The Death of Anglo-Saxon England by N J Higham

The Diplomas of King Æthelred the Unready 978-1016 by Simon Keynes (if you can get a first edition do so, as the reprint doesn’t include the tables which is very frustrating).

Æthelred the Unready by Levi Roach

Æthelred the Unready, the ill-counselled king by Ann Williams

Cnut, England’s Viking King by M K Lawson

The Reign of Cnut: King of England, Denmark and Norway by Alexander Rumble

Cnut the Great by Timothy Bolton

Queen Emma and Queen Edith by Pauline Stafford

Edward the Confessor by Frank Barlow

Edward the Confessor by Tom Licence

Godwins: The Rise and Fall of a Noble Dynasty by Frank Barlow

Harold The Last Anglo Saxon King by Ian W Walker

Conquered: The Last Children of Anglo-Saxon England by Eleanor Parker

As a rule of thumb, and it’s not always right – the more expensive a resource- the more academic the contents.

I recommend anything written by Max Adams, Nick Higham (sometimes uses his initials), Pauline Stafford, Ann Williams, Levi Roach and Simon Keynes, amongst many others. Once you’ve got to grips with the period/person/event you’re interested in, start to dig a little deeper with more academic articles.

This post contains Amazon affiliate links.