Researching My Novel on the Brontë Sisters by Stephanie Cowell

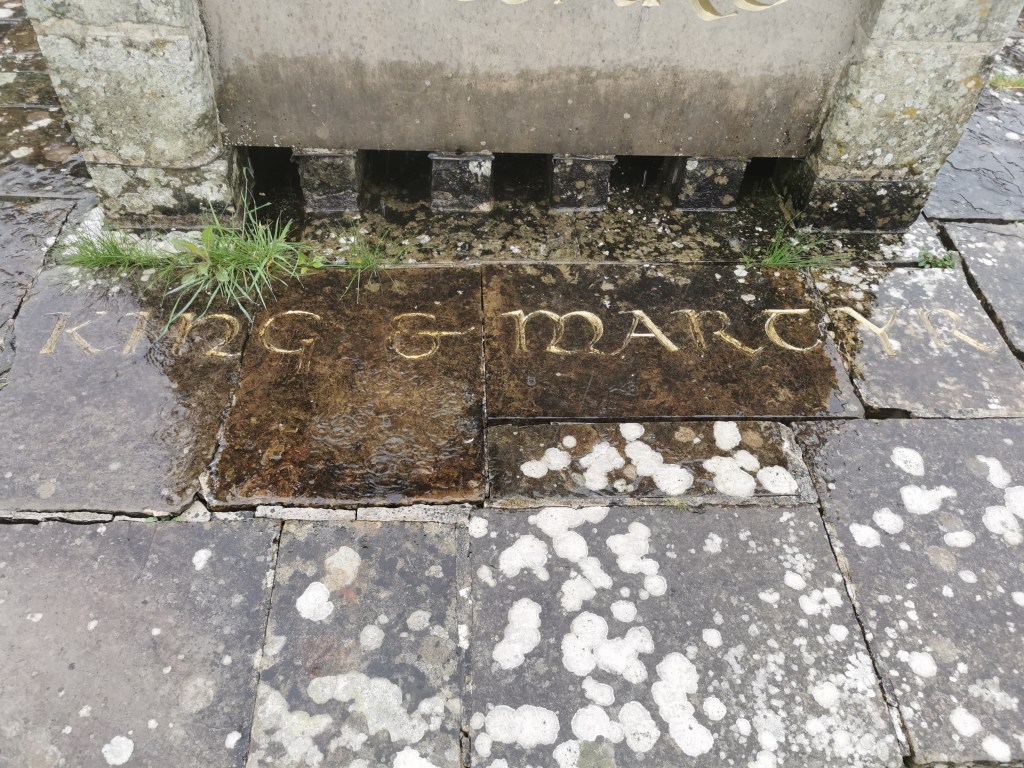

I simply love research. The opportunity to know more about my beloved historical characters and their surroundings and daily world is thrilling. Researching Charlotte, Anne and Emily Brontë, I had a chance to go to their village in Yorkshire (Haworth) and to the Parsonage where they lived with their clergyman father and wrote their books and what is more thrilling than that? I travelled there three times over many years.

In curated display cases, I could see the needles with which they sewed, the cup they drank from (imagine seeing Emily’s cup and knowing she might have paused in writing bits of Heathcliff to drink a sip of tea!), their clothing, their hand-written childhood magazines. I could walk around the house, climbing the steps they climbed every day. In the parlor/dining room, I marveled at the table where they wrote their books. (After a century or more of searching by scholars, the actual table was found in private hands and in 2015 it was brought back to the Parsonage. Someone has scratched “E” in the wood. Was it our Emily?)

So, my first research was going to the Parsonage, but a great deal of research of course was from biographies and household advice books and letters which describes event and feelings and hopes and fears. They describe loneliness.

Letters are the best! Charlotte wrote the most. She wrote hundreds to her best friend Ellen, pouring out her frustration about working in a teaching job at a boarding school until exhausted. She wrote about her family. She wrote to her publisher’s reader about her sadness over her alcoholic brother who could not keep a job. She wrote her married Belgium professor of her adoration of him. We have these letters almost two hundred years. They are from the writer who penned Jane Eyre’s passionate words, “Do you think, because I am poor, obscure, plain and little, I am soulless and heartless?”

Research! I have two bookshelves of biographies, literary analysis, life in Victorian England, books about the town of Haworth and the house, even a biography of the rather obscure man Charlotte eventually married. I just remembered that at one time my novel was not from the point of view of the two sisters, but only from his point of view. And like the larger part of stories I begin, it was not finished but eventually morphed into the final novel THE MAN IN THE STONE COTTAGE.

I try to keep my research books together also in certain shelves but some wander over the house. When I was a beginning writer and rather poor, I used the library for everything. Now I am afraid I mostly use the internet to buy obscure second-hand books.

It was however in an actual bookshop one day that I glanced at a shelf and found THE book I wanted, THE book I must have. This was in the days before the internet. I gasped so that I am fortunate the salesperson did not come rushing over to see if I was okay. Perhaps he was used to having people gasp over discovered books.

There is a problem with biographies. I went to a bookshop reading of one of Charlotte’s biographers, and someone asked her, “Have you written the definitive biography?” and she replied, “Oh no, I hope not. Every biographer sees her in a different way!” And that is true. Charlotte’s first biographer Mrs. Gaskell made Charlotte into a near saint. Others have emphasized the prickly side of her personality. Who would not be prickly with all her losses and griefs and hardships?

Emily and Anne have several biographies each, but less is known about them. These two sisters were more private and did not pour their heart out on paper, or perhaps fewer paper were kept.

Even when a novel is long finished and gone into the hands of readers, I love and long for the worlds where my beloved characters have walked. So, I go to wander in the streets of York or Paris or Florence, and if I wait, I will see one of my characters coming toward me. And likely he or she will smile and say, “There you are! Welcome back! We’ve been waiting for you!”

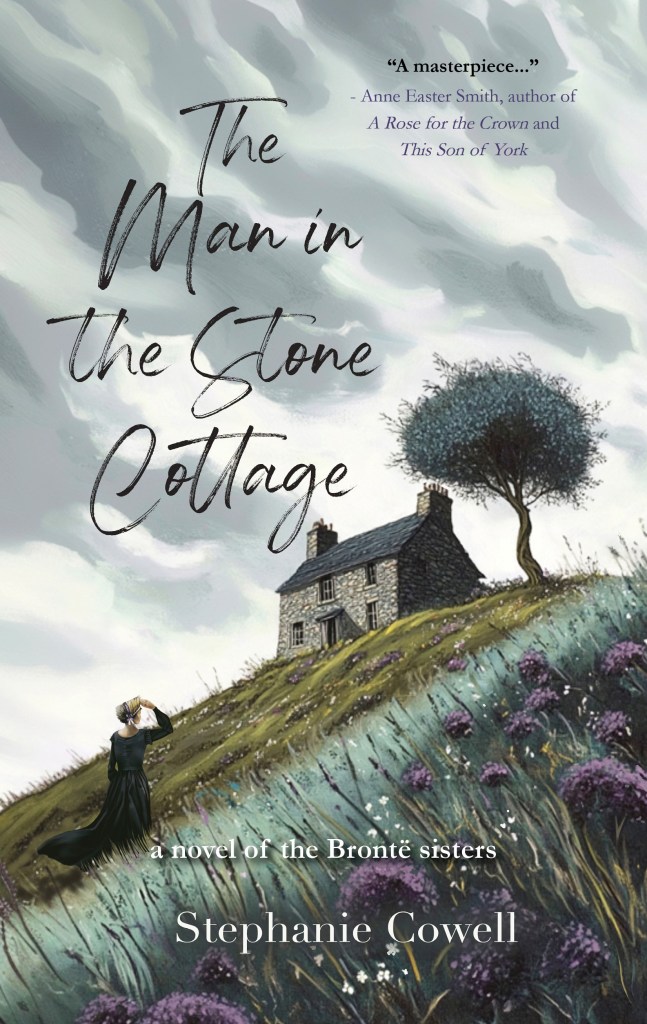

Here’s the blurb

“A haunting and atmospheric historical novel.” – Library Journal

In 1846 Yorkshire, the Brontë sisters— Charlotte, Anne, and Emily— navigate precarious lives marked by heartbreak and struggle.

Charlotte faces rejection from the man she loves, while their blind father and troubled brother add to their burdens. Despite their immense talent, no one will publish their poetry or novels.

Amidst this turmoil, Emily encounters a charming shepherd during her solitary walks on the moors, yet he remains unseen by anyone else.

After Emily’ s untimely death, Charlotte— now a successful author with Jane Eyre— stumbles upon hidden letters and a mysterious map. As she stands on the brink of her own marriage, Charlotte is determined to uncover the truth about her sister’ s secret relationship.

The Man in the Stone Cottage is a poignant exploration of sisterly bonds and the complexities of perception, asking whether what feels real to one person can truly be real to another.

Praise for The Man in the Stone Cottage:

“A mesmerizing and heartrending novel of sisterhood, love, and loss in Victorian England.” – Heather Webb, USA Today bestselling author of Queens of London

“Stephanie Cowell has written a masterpiece.” – Anne Easter Smith, author of This Son of York

“With The Man in the Stone Cottage, Stephanie Cowell asks what is real and what is imagined and then masterfully guides her readers on a journey of deciding for themselves.” – Cathy Marie Buchanan, author of The Painted Girls

“The Brontës come alive in this beautiful, poignant, elegant and so very readable tale. Just exquisite.” – NYT bestseller, M.J. Rose

“Cowell’s ability to take readers to time and place is truly wonderful and absorbing.” – Stephanie H. (Netgalley)

“Such a lovely, lovely book!” – Books by Dorothea (Netgalley)

Purchase Link

https://books2read.com/u/mqLV2d

Meet the author

Stephanie Cowell has been an opera singer, balladeer, founder of Strawberry Opera and other arts venues including a Renaissance festival in NYC.

She is the author of seven novels including Marrying Mozart, Claude & Camille: a novel of Monet, The Boy in the Rain and The Man in the Stone Cottage. Her work has been translated into several languages and adapted into an opera. Stephanie is the recipient of an American Book Award.

Connect with the author