Here’s the blurb

A King in crisis, a Queen on trial, a Kingdom’s survival hangs in the balance.

Londonia, AD835

The deadly conspiracy against the children of Ealdorman Coenwulf is to be resolved. Those involved have been unmasked and arrested. But will justice prevail?

While the court convenes to determine the conspirator’s fate, King Wiglaf’s position is precarious. His wife, Queen Cynethryth, has been implicated in the plot and while Wiglaf must remain impartial, enemies of the Mercia still conspire to prevent the full truth from ever being known.

As Merica weeps from the betrayal of those close to the King, the greedy eyes of Lord Æthelwulf, King Ecgberht of Wessex’s son, pivot once more towards Mercia. He will stop at nothing to accomplish his goal of ending Mercia’s ruling bloodline.

Mercia once more stands poised to be invaded, but this time not by the Viking raiders they so fear.

Can Icel and his fellow warriors’ triumph as Mercia once more faces betrayal from within?

An action packed, thrilling historical adventure perfect for the fans of Bernard Cornwell and Matthew Harffy

Here’s the purchase link (ebook, paperback, hardback and audio)

books2read.com/BetrayalofMercia

Crime and Punishment in Saxon England

In Betrayal of Mercia, the seventh book in the Eagle of Mercia Chronicles featuring young Icel, I’ve done something that I don’t ‘think’ anyone else has done before. I’ve staged a criminal trial, making Betrayal part court-room drama and part action-thriller (you know Icel is always going to end up in a fight at some point). However, there are odd things about Saxon England that we have no information about – one of them is how often people actually went to church once Christianised, another is exactly how the law was enacted.

This might seem like an odd thing to say. Everyone knows there are surviving law codes from the era, especially from the eleventh century, with the inspiring names of Æthelred I or Cnut II, and indeed, the earliest law code dates back to Ine, in the seventh century, from which we can glean such titles as Wealas or foreigner, but applied to the Welsh, who had different wergild payments and punishment from the Saxons. But, there has long been an argument about how much these law codes reflect practise as opposed to an ideal. And some of the elements we ‘think we know’ turn out to be on much less steady ground. And, at the heart of all this is a problem with our current perceptions of ‘right,’ ‘wrong,’ and ‘justice.’ We ‘appear’ to look at these elements of our current legal system in a way very different to the era.

When studying what records we do have, we’re greeted with some interesting terms. ‘Thereafter there would be no friendship,’ appears in a charter detailing a land dispute in the later tenth century – between Wynflæd and Leofwine (S1454 from 990 to 992). In this, despite whoever was in the wrong or the right, the decision was made which was something of a compromise – both injured parties had to make concessions. No one truly ‘won’, even though Wynflæd had many who would speak on her behalf, including the king’s mother, and the Archbishop of York, and had appealed directly to the king, Æthelred II, for assistance, only for Leofwine to refuse to attend his summons saying that royal appeals couldn’t precede a regional judgement on the matter.

In the famous case of Lady Eadgifu of Wessex (recorded in charter S1211), the mother of Kings Edmund and Eadwig (who features in the Brunanburh series), her landholdings at Cooling required the intervention of her husband, stepson, son and grandson, in a long-running debacle which was never really resolved until her grandson intervened close to the end of her life. Even though she appears to have held the ‘landboc’ – the title deed for the land – and was a highly regarded member of the royal family, this wasn’t enough to stop counterclaims. In the end, she assigned the land to the Christ Church religious community, and that way, no one actually benefitted apart from the church.

These cases both refer to land disputes, which are one of the larger areas of document survival, along with wills. But what about crimes visited against the king’s mund (both his physical person and his physical kingdom)? Here, we’re again confronted with little knowledge. We know of ealdormen being banished (under Æthelred II) and this attests to another element of the practise of law which is perhaps surprising. There does seem to have been an aversion to capital punishment (as Rabin details in his book mentioned below). And there was also a concern that the right sentence was handed to individuals – it was as bad to incorrectly punish as it was to have committed the crime.

In trying to stage a trial set in the Saxon period (which I now realise was a bit bonkers), I’ve relied heavily on a very short book, Crime and Punishment in Anglo-Saxon England by Andrew Rabin, and also his translations of the Old English Legal Writings by (Archbishop) Wulfstan (from the 1000s), from which I’ve determined how many oath-helpers people must have based on the Mercian Wergild listed within the source documents. This suggests the value placed on individuals – the king, of course, being at the top. Each individual had a wergild value and equally, each individual had a required value for the number of oath-helpers who would stand as surety for them if asked to detail what they had ‘seen and heard’ in a trial situation. The implication being that those who needed the least oath-helpers were more trustworthy than those who needed many – so a king might need no one, after all, he was the king, whereas a warrior might need a few, and a ‘normal’ person might need many.

This feels like a very different world to the one we ‘know,’ where transgressions are punished by custodial sentences and fines and where the burden of proof rests on the shoulders of those prosecuting the alleged offenders.

It has certainly been an interesting experiment, and one I hope readers will enjoy, and more importantly, one which I’ve managed to convey largely ‘correctly.’

I’ll also be sharing more posts, including one on Mercia’s ‘Bad Queens,’ and one on the maps in the books.

Not started the series yet? Check out the series page on my blog.

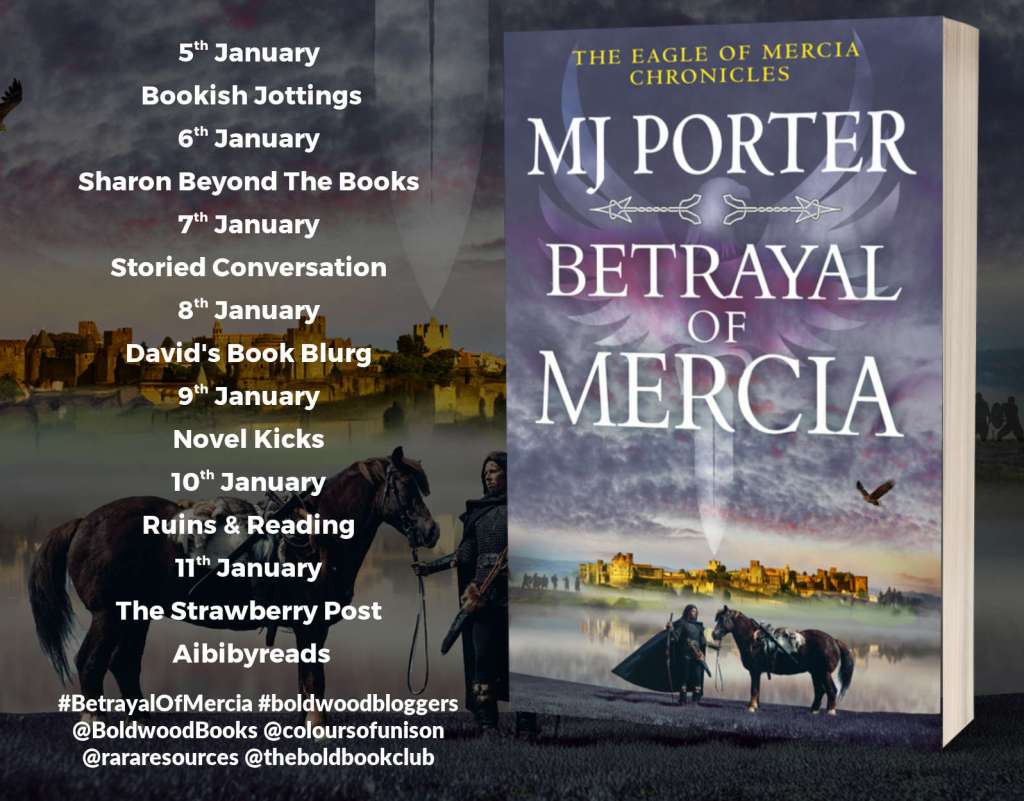

Check out the blog tour for Betrayal of Mercia

A huge thank you to all the book bloggers and Rachel at Rachel’s Random Resources for organising.

Discover more from MJ Porter

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 thoughts on “It’s happy release day to Betrayal of Mercia, so I’m sharing a post about Crime and Punishment in Saxon England”