Why Brunanburh?

In 2014, I had the ‘amazing’ idea to write a novel about the events that led to the famous battle of Brunanburh in 937 – the greatest battle on British soil that few people have ever heard about (Or certainly hadn’t heard about back then – who knew Uhtred of Bebbanburg would be taking part in it).

My reasons were two-fold. I’d just read Sarah Foot’s monograph on Athelstan, and the UK was in the grip of a vote for Scottish Independence. It made me consider the union of the kingdoms of Wales, Scotland, England and Northern Ireland and the history behind it. But, it also stemmed from my own frustration with the way we’re taught history in the UK. ‘United’ it might say but if you go to school in England, Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland you will be taught the ‘history’ of those kingdoms (and only those kingdoms)- that was when I was a kid, and I think it’s still true – very little ‘joined up’ thinking, and this is something that continues to cause problems today, and not just in the UK, but everywhere. Country-specific agendas fall down when looking at periods before these kingdoms actually existed – and the desire to see the ‘march’ towards unity as simple also misses the naunces.

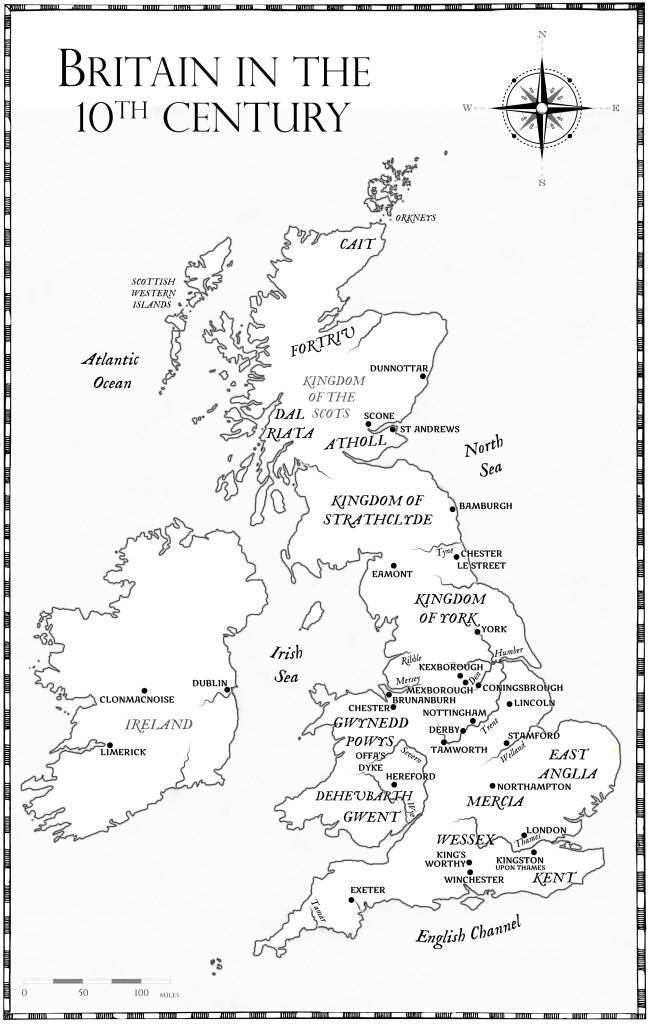

In the first book in what became the Brunanburh Series, I wanted to examine these kingdoms – to unpick the seeming ‘inevitability’ of it all – and it massively helped that despite what might come before, and after, and as little as it may seem – we do know a surprising amount about the kings who fought at Brunanburh. What we don’t know (although the Wirral is now almost ‘accepted’ as the correct location) is where Brunanburh took place, and what actually led to it. It was time for me to get writing.

1100th Anniversary of Athelstan becoming king of Mercia

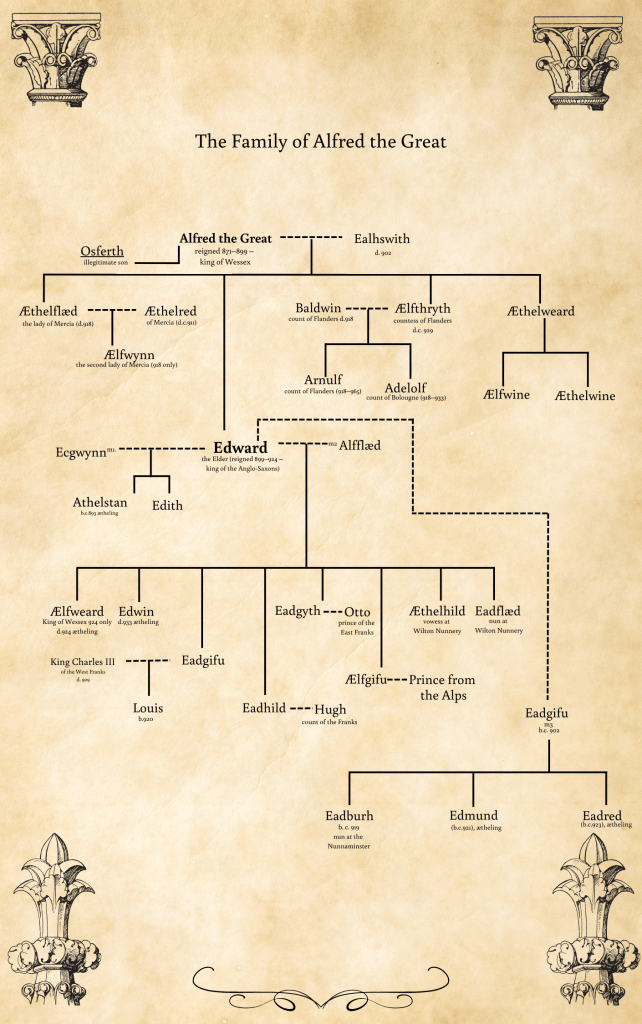

2024 marks the 1100th anniversary of King Athelstan becoming king of Mercia (although his coronation as king of the English took place in 925 – so a year later (read my post about this period here). While he has been often overlooked between the alleged ‘greatness’ of King Alfred (871-899), and the alleged ‘failure’ of King Æthelred II (978-1033/1013-1016), Alfred’s great great grandson, more and more historical investigation is being undertaken on Athelstan, and indeed, his half-brother, Edmund, who is one of the other characters in the series. (It might also have helped that Athelstan features in Bernard Cornwell’s The Last Kingdom series). A spotlight is being shone on all Athelstan accomplished, and the move is also encompassing Edmund, (as well as Eadred, and Eadwig – these three often overlooked).

Non-fiction books to read

And this investigation is also looking at events in what would be Scotland, Ireland and Wales, as well as the Norse kings of Jorvik. The approach I’ve taken, is one that historians are examining – Alex Woolf’s From Pictland to Alba and Claire Downham’s Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland (they did it before me – but their books have helped me massively), as well as Max Adams’ Ælfred’s Britain which focused on much more than just Alfred.

My conclusions from writing about this period?

What then can I say after four books considering this period? Quite simply, nothing is as easy to explain or account for as might be hoped. The sources that have survived come with so many explanations about translation (they are not written in English – and indeed we have Old English, Latin, Old Irish, Old Welsh etc) bias, survival, manipulation, and corroboration (one source is often used to corroborate another) that sometimes it feels easier to hold my hands up and say ‘who knows?’

Attempts to draw together a cohesive narrative are constantly thwarted. One historian may argue for one thing, another for another. Every person who studies the period will have their own levels of ‘acceptable’ when looking at the sources. I am always wary of Saints Lives – they were not intended, and can not be, accepted as historical ‘fact’ but they do tell us a lot about reputation – another interesting facet to consider. The Icelandic Sagas must also come with a host of caveats. I also have to rely on translations and therefore remove myself from the original intention of the scribe once more.

The joy of this period is in the nuances that can be exploited – it is also where most people are likely to argue. And indeed, readers may fail to comprehend these nuances – hence the ‘it’s too predicatable’ complaint- I imagine all of ‘my’ kings would have welcomed the preditability of knowing the eventual outcome.

Trying to explain concepts such as ‘this is the first king of the English,’ ‘Hywel’s a king of all the Welsh’ falter because my audience expect these places to be united and under one king – but alas, were rarely that. The other England-specific failure to teach history before ‘1066’ also adds to these problems. The Saxon period is deemed as ‘weird,’ (the names, oh the names). There is so much going on, that even I have fallen down and made mistakes, and only with a sort of ‘doh’ moment made the connection between the name Brunanburh and the element of most interest ‘burh.’ (Thank you Bernard Cornwell for that moment of understanding – I still feel very, very stupid about it – not his fault).

Team Norse, Team England, Team Wales or Team Scots?

To tell a story such as this involves standing on the shoulders of giants. I am indebted to them – and sometimes, a bit narked that they won’t give me any definites either – what I will say is this – I understand a lot more now. I hope others do as well. And whether you’re Team England, Team Norse, Team land of the Scots, or Team what would be Wales, I hope you enjoyed meeting these long-dead men and women and realising that they were just as shifty, ambitious and perhaps, blood-thirsty, as people are today. I really can’t ask for more than that, other than you read the non-fiction for the period as well, and hopefully, enjoy it.

books2read.com/KingsOfConflict10th

Check out the Brunanburh Series page for more information and lots more links to blog posts.

Discover more from MJ Porter

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.