Who were the many daughters of Edward the Elder who married into the ruling families in East and West Frankia?

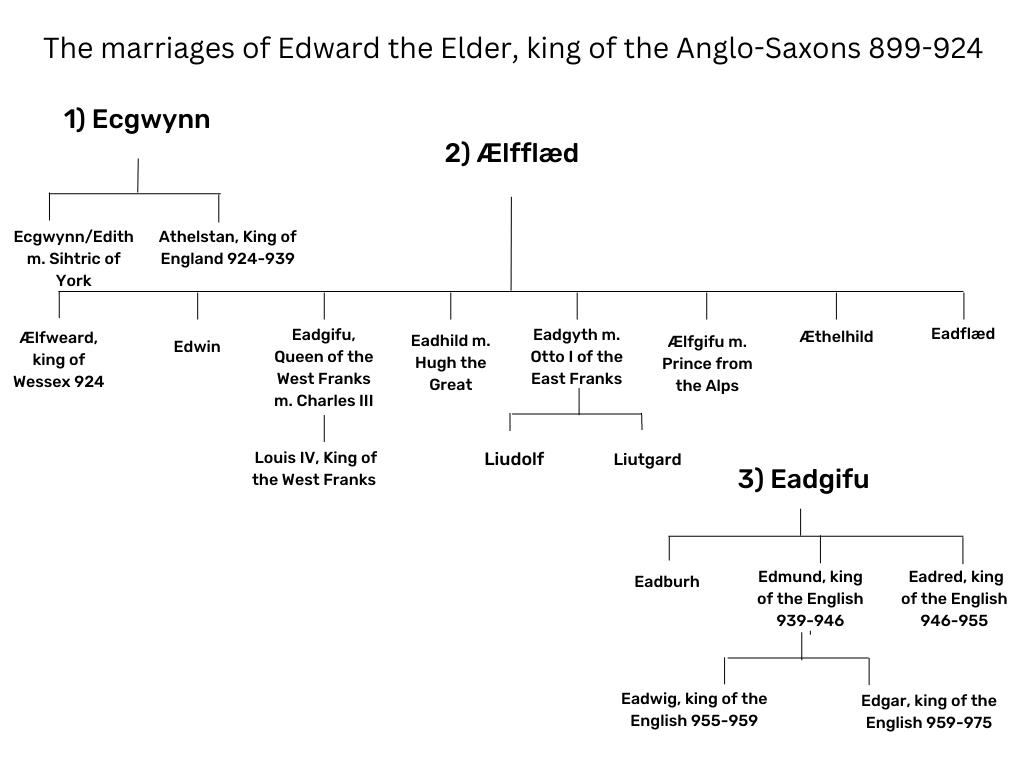

Edward the Elder was married three times, to an unknown woman- who was the mother of the future King Athelstan, to Lady Ælfflæd – who was the mother of the future, and short-lived King Ælfweard, and finally to Lady Eadgifu – who was the mother of the future kings Edmund and Eadred. But, while each woman was mother to a future kings, this story focuses on the daughters. And there were a lot of them, and their lives were either spent in making prestigious marriages, or as veiled women – whether professed religious, or merely lay women living in a nunnery or an isolated estate.

Eadgifu[i], was perhaps the oldest daughter of King Edward the Elder, and his second wife, Lady Ælfflæd. She was the first to marry, to Charles III, King of West Frankia (879-929), who ruled the kingdom from 898-922. This union is written about by the near-contemporary writer Æthelweard in the prologue to his Chronicon.

‘Eadgyfu [Eadgifu] was the name of the daughter of King Eadweard [Edward], the son of Ælfred…and she was your great-aunt and was sent into the country of Gaul to marry the younger Charles.’[ii]

This was a marriage of some prestige for the granddaughter of King Alfred and one which saw her become the Queen of the West Franks.

Charles was much her senior, and one with many illegitimate sons, born to Charles’ concubines,[iii] as well as six daughters with his first wife, Frederuna.[iv] But, on the death of his first wife in 917, Charles had no legitimate heir to rule after him.

Eadgifu isn’t mentioned in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but she does feature in The Annals of Flodoard of Reims 919-966. historian Sarah Foot maintains that as Eadgifu’s marriage isn’t mentioned in the work of Flodoard, it must have occurred before he began writing and, therefore before 919.[v]

Yet, Charles III didn’t rule a quiet kingdom, far from it, in fact. Louis, Eadgifu and Charles’ son was born in 921-922, and his birth seems to have coincided with Charles losing control of his kingdom to an overpowerful nobleman, who ruled as Robert, King of the West Franks from 922-923 when Charles III was briefly reinstated before being deposed once more and imprisoned, where he wound remain until his death in 929.

It is known that Louis was sent to the Wessex royal court, to be fostered firstly by her father and then by her half-brother, Athelstan.[vii] It’s likely that Louis was a similar age to Edward the Elder’s younger children. If Eadgifu returned to Wessex in 923 as well, she would have been in Wessex when her father died, her full-brother became king, albeit briefly, only for Athelstan, her half-brother, to become king.

On Charles’ death, in 929, Eadgifu was certainly once more living in England with her son Louis. And she would do so until 936 when Louis regained his kingship, and Eadgifu returned to West Frankia as the king’s mother.

Louis’ reinstatement does seem to have had much to do with his uncle by marriage, Hugh of the Franks (c.895-956), married to his aunt Eadhild.

We’re told by Flodoard,

‘Louis’s uncle, King Athelstan, sent him to Frankia along with bishops and others of his fideles after oaths had been given by the legates of the Franks. Hugh and the rest of the nobles of the Franks set out to meet Louis when he left the ship, and they committed themselves to him on the beach at Boulogne-sur-Mer just as both sides had previously agreed. They then conducted Louis to Laon and he was consecrated king, anointed and crowned by Lord Archbishop Artoldus (of Rheims) in the presence of the leading men of the kingdom and more than twenty bishops.’[viii]

But all might not be quite as bland as Flodoard states. Hugh might have been married to Eadhild, Louis’ aunt, but he was also an extremely powerful nobleman, brother to the previous king, Ralph. As McKitterick states, ‘No doubt Hugh calculated that he would be able to exert effective power within the kingdom as the young monarch’s uncle, chief advisor and supporter.’[ix]

Young Louis would only have been about sixteen when he was proclaimed king of West Frankia. He was also a virtual stranger to those he now ruled, having been fostered at the Wessex/English court since 923.

Louis was consecrated on 19th June 936. What happened during the early years of his rule is explored in The King’s Daughters, through the eyes of his mother.

(Read on below the references to find out about the other daughters).

[i] PASE Eadgifu (3)

[ii] Campbell, A. ed The Chronicle of Æthelweard: Chronicon Æthelweardi, (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1962), Prologue p.2

[iii] The matter of marriages, and concubinage is gathering increasing levels of interest. It is becoming apparent that the need for legitimate marriages was a matter laid down by the Church as a means to garner legitimacy. Before this, unions of concubinage may have held as firmly as church recognised marriages.

[iv] Details taken from McKitterick, R. The Frankish Kingdoms Under The Carolingians, 751-987, (Longman, 1983), p. 365 Genealogical table

[v] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.46

[vi] Bachrach, B.S. and Fanning, S ed and trans, The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916-966 (University of Toronto Press, 2004), 20A

[vii] William of Jumieges in his Gesta Normannorum Ducum III.4 (PASE)

[viii] Bachrach, B.S. and Fanning, S ed and trans, The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916-966 (University of Toronto Press, 2004), 18A (936). Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.168

[ix] McKitterick, R. The Frankish Kingdoms Under The Carolingians, 751-987, (Longman, 1983), p.315

[x] Van Houts, E. M. C., trans. The Gesta Normannorum Ducum of William of Jumieges, Orderic Vitalic, and Robert of Torigni, (Clarenden Press, Oxford, 1992) pp82-83 Book III.4

[xi] Bachrach, B.S. and Fanning, S ed and trans, The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916-966 (University of Toronto Press, 2004), 33G

[xii] PASE Greater Domesday Book 353 (Lincolnshire 18:25)

Eadhild[i], perhaps the second daughter of Edward the Elder and his second wife, Lady Ælfflæd, marriage Hugh the Great, later known as dux Francorum, in another continental dynastic marriage similar to that of her sister. Under 926, Flodoard of Reims states, ‘Hugh, son of Robert, married a daughter of Edward the Elder, the king of the English, and the sister of the wife of Charles.’[ii] This wasn’t Hugh’s first marriage, but that union was childless.

There’s no record of the marriage in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. However, once more, it is mentioned in Æthelweard’s Chronicon, ‘Eadhild, furthermore, was sent to be the wife of Hugo, son of Robert.’[iii] And also in Flodoard’s Annals, as mentioned above.

There is a later, really quite detailed account in the twelfth-century source of William of Malmesbury’s Gesta Regum Anglorum. He describes Eadhild as ‘in whom the whole mass of beauty, which other women have only a share, had flowed into one by nature,’ was demanded in marriage from her brother by Hugh of the Franks.’[v]

Hugh was a very wealthy individual. His family, ‘commanded the region corresponding to ancient Neustria between the Loire and the Seine, except for the portions ceded to the Vikings between 911 and 933. Hugh also possessed land in the Touraine, Orleanais, Berry, Autunois, Maine and north of the Seine as far as Meaux, and held the countships of Tours, Anjou and Paris. Many powerful viscounts and counts were his vassals and deputies…a number of wealthy monasteries were also in Robertian [the family named after his father] hands. Hugh himself was lay abbot of St Martin of Tours, Marmoutier, St Germain of Auxerre (after 937), St Denis, Morienval, St Riquier, St Valéry and possibly St Aignan of Orleans, St Germain-des-Pres and St Maur des Fosses.’[viii]

Eadhild, sadly died in 937, childless, and in The King’s Daughters her death sets in motion some quite catastophic family feuding.

(Read on below the references to learn more about The King’s Daughters)

[i] Eadhild (1) PASE

[ii] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.47. Bachrach, B.S. and Fanning, S ed and trans, The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916-966 (University of Toronto Press, 2004), 926

[iii] Campbell, A. ed The Chronicle of Æthelweard: Chronicon Æthelweardi, (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1962), Prologue p.2

[iv] Bachrach, B.S. and Fanning, S ed and trans, The Annals of Flodoard of Reims, 916-966 (University of Toronto Press, 2004), 8E

[v] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.47. Mynors, R.A.B. ed and trans, completed by Thomson, R.M. and Winterbottom, M. Gesta Regvm Anglorvm, The History of the English Kings, William of Malmesbury, (Clarendon Press, 1998),ii,135,pp218-9

[vi] McKitterick, R. The Frankish Kingdoms Under The Carolingians, 751-987, (Longman, 1983), p.314

[vii] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.47

[viii] McKitterick, R. The Frankish Kingdoms Under The Carolingians, 751-987, (Longman, 1983), p.314

Eadgyth,[i] has her marriage mentioned in the entry for the D text of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle under the year 924. Alongside Athelstan’s unnamed biological sister, she’s the only one of Edward’s daughters to be mentioned in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. ‘..and he gave his sister across the sea to the son of the King of the Old Saxons (Henry).’[ii]Sarah Foot notes that in the Mercian Register section of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, this sentence in 924 is unfinished. The D text chooses to complete this sentence differently, referencing the union of Eadgyth to Otto, as opposed to the union of Athelstan’s unnamed sister to Sihtric of York. This then explains why the reference occurs in the annal entry for 924, whereas the union took place in 929/30, following a Saxon military triumph over the Slavs in the late summer of 929.[iii]

Æthelweard’s Chronicon again adds to our knowledge by informing his readers that Athelstan sent two of his sisters for Otto to choose the one he found most agreeable to be his wife.

‘King Athelstan sent another two [of his sisters] to Otho, the plan being that he should choose as his wife the one who pleased him. He chose Eadgyth.’[v] This story is also told in Hrotsvitha’s Gesta Ottonis. ‘he bestowed great honour upon Otto, the loving son of the illustrious king, by sending two girls of eminent birth, that he might lawfully espouse whichever one of them he wished.’[vi]

Bishop Cenwald of Worcester accompanied both sisters to Saxony. The account of his visit can be witnessed in a confraternity book from St Galen, where he signed his name. Eadgyth was certainly the mother of a son and a daughter, Liudolf and Liudgar.

Read The King’s Daughters to discover more about her story.

[i] PASE Eadgyth (2)

[ii] Swanton, M. trans and edit The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (Orion Publishing Group, 2000), p105. And Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.49 n69

[iii] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.48

[iv] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.48

[v] Campbell, A. ed The Chronicle of Æthelweard: Chronicon Æthelweardi, (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1962), Prologue p.2

[vi] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.49, but Hrotsvitha, Gesta Ottonis, lines 79-82 and 95-8 ed. Berchin 278-9

[vii] Swanton, M. trans and edit The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (Orion Publishing Group, 2000), C p.124

King Athelstan is said to have sent two sisters to the court of Otto of Saxony, for him to determine which he would marry. This sister has vexed historians, even Æthelweard in his Chronion is unsure of her name,[i] and he wrote his text much earlier than other sources available, by c.978 at the latest. It would be hoped that a woman who left England only forty years earlier might have been remembered. Æthelweard believed she had married, ‘a certain king near the Alps, concerning whose family we have no information, because of both distance and the not inconsiderable lapse of time.’[ii] He held out hopes that Matilda, to whom he dedicated his work, might be able to tell him more.

‘Louis, brother of Rudolf of Burgundy, and his English wife were influential figures in that region when Rudolf died young, leaving only a child, Conrad, as heir.’[vi]

More than this, it is impossible to say. It is unsettling to realise that the daughter of one of the House of Wessex’s kings could so easily be ‘lost’ to our understanding today, and indeed, to that of her descendants only forty years later. This raises the awareness that if noble women could disappear from the written records, then so to could almost anyone.

[i] This sister may appear as Anonymous 921 on PASE

[ii] Campbell, A. ed The Chronicle of Æthelweard: Chronicon Æthelweardi, (Thomas Nelson and Sons Ltd, 1962), Prologue p.2

[iii] Mynors, R.A.B. ed and trans, completed by Thomson, R.M. and Winterbottom, M. Gesta Regvm Anglorvm, The History of the English Kings, William of Malmesbury, (Clarendon Press, 1998), pp.199-201

[iv] Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011) p.51

[v] Please see Foot, S Athelstan (Yale University Press, 2011), p.51 for this fascinating discussion in its entirety.

[vi] Foot, S ‘Dynastic Strategies: The West Saxon royal family in Europe,’ in England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876-1947) (Brepols, 2012), p.250

The King’s Daughter is the story of these women and their lives (mostly) in Continental Europe, and I hope you’ll enjoy it.

Check out The Tenth Century Royal Women page.

Interested in the real women? Please check out my non-fiction title, The Royal Women Who Made England.

Posts

Discover more from MJ Porter

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

6 thoughts on “Who were the daughters of Edward the Elder who married into the ruling families of East and West Frankia? #histfic #non-fiction”