A Conspiracy of Kings – a little bit of history (may contain spoilers for my fictional recreation of Lady Ælfwynn

In the sequel to The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter, the story of Lady Ælfwynn continues. She is The Second Lady of Mercia, but everything isn’t as it seems. In the various recensions of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, an attempt can be made to piece together what befalls her.

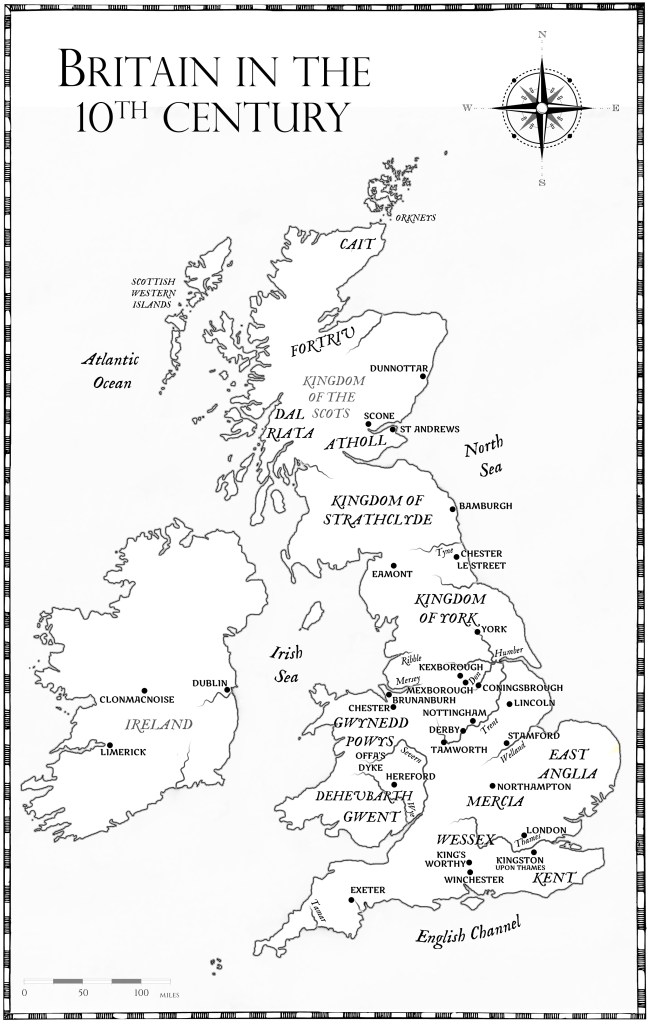

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle A version doesn’t mention Ælfwynn at all but instead has King Edward of Wessex/the Anglo-Saxons taking control of Tamworth as soon as his sister dies in June 918.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle E only mentions Lady Æthelflæd’s death in 918 and not what happens immediately after in Mercia. Lady Ælfwynn’s fate, however, is recorded in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle C. We’re told that she was deprived of all power and ‘led into Wessex three weeks before Christmas.’ This entry is dated 919, although it’s normally taken to mean 918 due to a disparity between the dating in this part of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle – known as the Mercian Register – where a new year starts in December as opposed to in the Winchester version of The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle where the new year starts in September.

These details are stark, offering nothing further. What then actually happened to Lady Ælfwynn? Was she deprived of her power? Was she deemed unsuitable to rule?

What adds to the confusion surrounding Lady Ælfwynn is that other than this reference in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, she doesn’t appear in any of the later sources. It’s as though she simply ceased to exist.

Two intriguing suggestions have been put forward to explain what happened to Lady Ælfwynn, both with some tenous corroboration.

Did she become a nun or, perhaps, a religious woman?

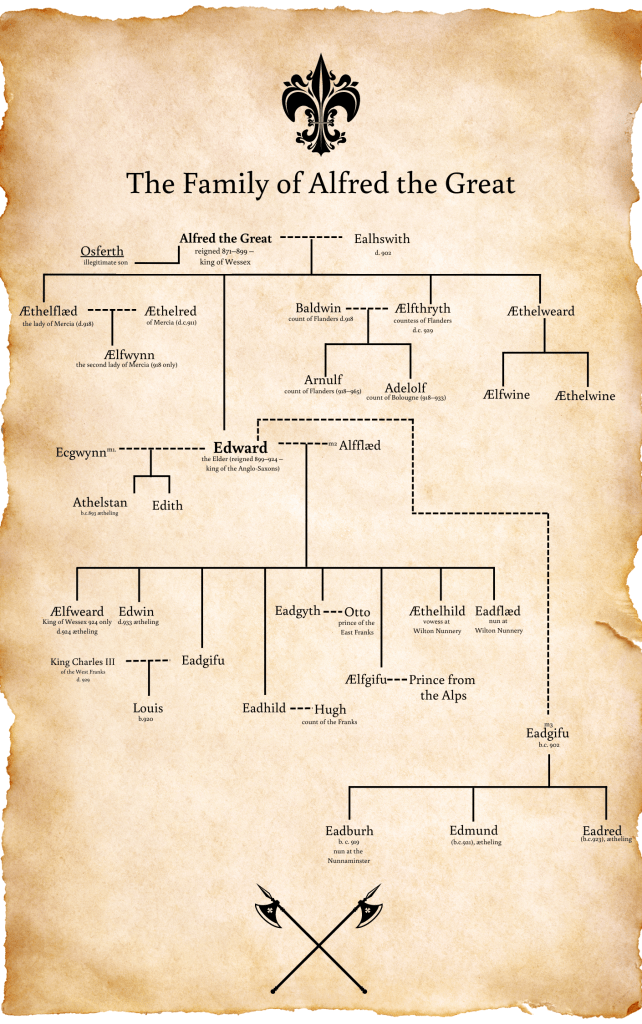

A later charter dated to 948 and promulgated by King Eadred is to an ‘Ælfwyn, a religious woman,’ and shows land being exchanged in Kent for two pounds of purest gold. (S535) There’s no indication that this Ælfwyn is related to our Ælfwynn or even to King Eadred. But, there remains the possibility that it might just have been the same woman, after all, Eadred would have been Ælfwynn’s cousin. Charter S535 survives in only one manuscript.

Alternatively, and based on a later source, Ramsey Abbey’s Book of Benefactors, we learn the following:

‘he [Athelstan Half-King] bestowed marriage upon a wife, one Ælfwynn by name, suitable for his marriage bed as much as by the nobility of her birth as by the grace of her unchurlish appearance. Afterwards she nursed and brought up with maternal devotion the glorious King Edgar, a tender boy as yet in the cradle. When Edgar afterwards attained the rule of all England, which was due to him by hereditary destiny, he was not ungrateful for the benefits he had received from his nurse. He bestowed on her, with regal munificence, the manor of Weston, which her son, the Ealdorman, afterwards granted to the church of Ramsey in perpetual alms for her soul, when his mother was taken from our midst in the natural course of events.’[i]

Which alternative is it?

There are only eight women named Ælfwynn listed in the Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England (PASE), a fabulous online database. Of these, one is certainly Ælfwynn, the second lady of the Mercians, and one is undoubtedly the religious woman named in the charter from 948. (When the identification is not guaranteed, multiple entries are made in this invaluable online database). The other five women were alive much later than the known years Ælfwynn lived. One of the entries might possibly relate to her, but that’s all the information known about her.

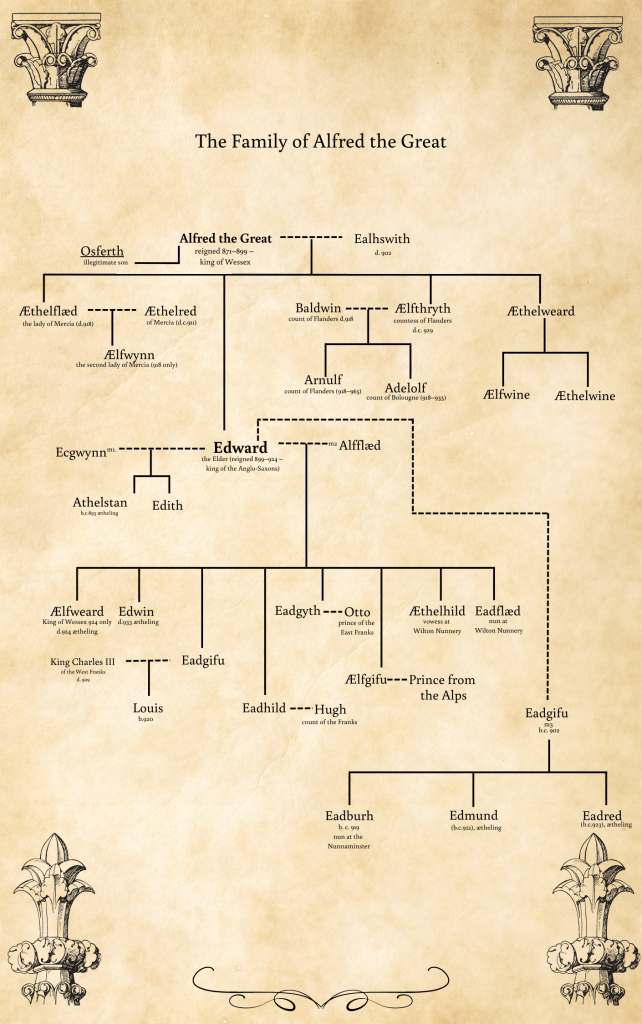

And this is far from unusual for many of the women of the House of Wessex. Some women are ‘lost’ on the Continent. Some are ‘lost’ in England.

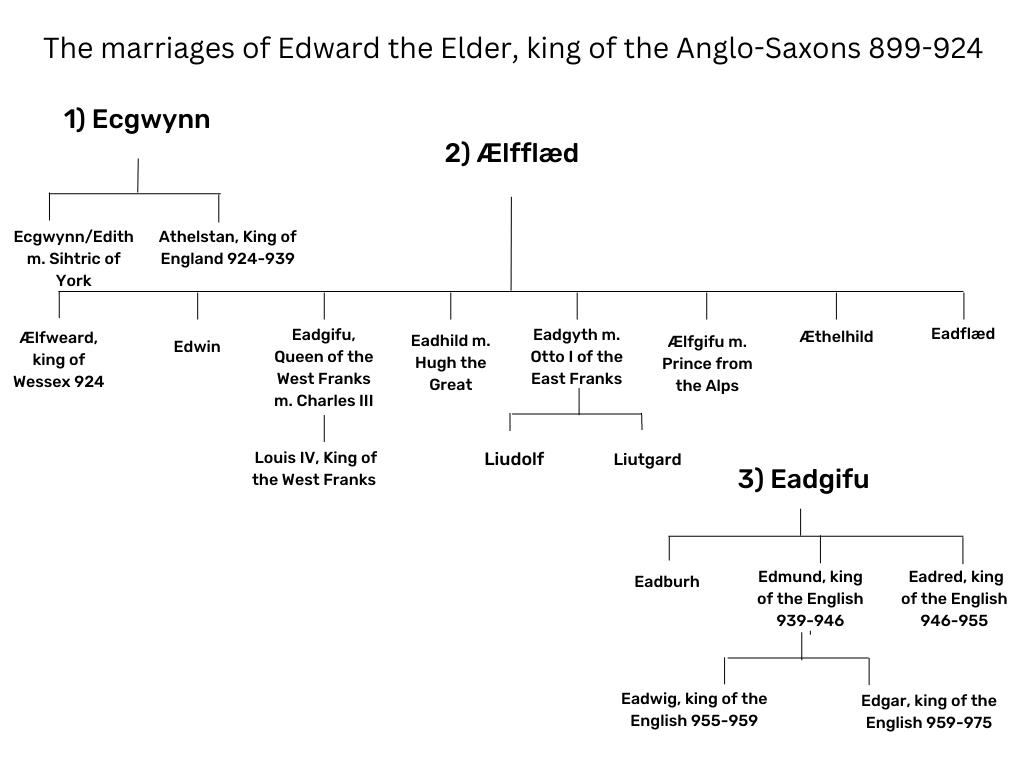

‘Were it not for the prologue to Æthelweard’s Latin translation of an Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, we would know of only six tenth-century royal daughters or sisters from early English sources and the names of only four of them. Three of these named ones are nuns or abbesses. Only Ælfwynn, the daughter of Æthelflæd and Æthelred of Mercia, and the two daughters of Edward/sisters of Athelstan who married Otto I and Sihtric of York, appear in the witness lists of charters, though Eadburh, daughter of Edward the Elder, is a grantee of a charter of her brother Athelstan.’[ii]

Reconstructing a ‘possible’ life for Lady Ælfwynn was the inspiration for both The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter and A Conspiracy of Kings, and the potential for family betrayal, politicking, and war with the Viking raiders was just too good an opportunity to miss.

[i] Edington, S and Others, Ramsey Abbey’s Book of Benefactors Part One: The Abbey’s Foundation, (Hakedes, 1998) pp.9-10

[ii] Stafford, P. Fathers and Daughters: The Case of Æthelred II in Writing, Kingship and Power in Anglo-Saxon England, (Cambridge University Press, 2018) p.142