I’m delighted to welcome Catherine Kullmann to the blog with a post about her historical fiction research.

Writing Historical Fiction—The Research

Whether we talk about fictionalised history or fictional biography where the story of real-life characters is told, or genre fiction such as historical romance or historical mystery where fictional characters are placed in an historical setting, the onus is on the author to transport the reader to an unfamiliar society recreated partly from familiar facts and partly from a myriad of tiny, new details so that it seems as real as the world of today. The setting must ring true and the characters’ actions must be determined by the laws, mores and ethics of their time, not ours. Sometimes this may horrify us; at other times we find it liberating and long for more romantic, more adventurous, perhaps simpler bygone days.

Except where a real-life character such as one of the patronesses of Almack’s is introduced for authenticity, my Regency novels are pure fiction. I create the characters and the story arc but to make them and their world come to life, I must know the period inside out; not only the main facts and important dates but also the minor ones and the trivia of daily life. It is essential that I know the social structures, ethics, mores and beliefs of the period, constraints which add conflict and tension to the story and enable readers to step into the setting as easily as they step out of their front doors,

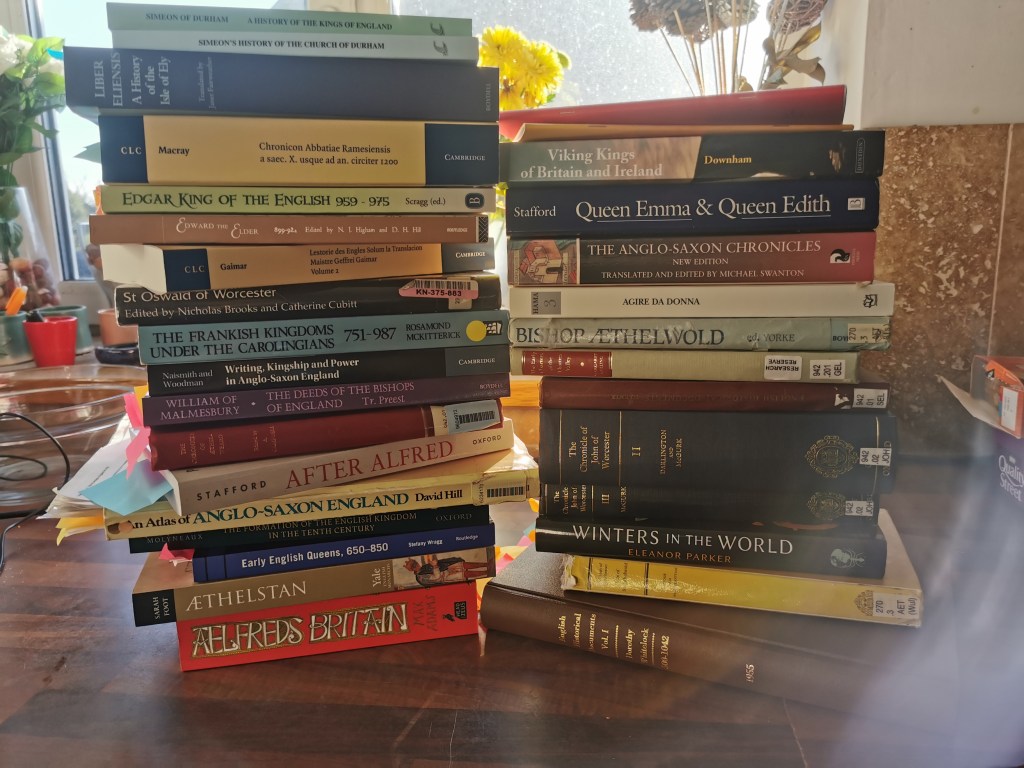

But where do I get this information? Primarily by reading. I have a large research library and a huge database of historical facts and trivia. Everything is grist to my mill—contemporary memoirs, diaries, letters, novels, plays, poetry, newspapers and magazines, etiquette and letter-writing manuals, cookery books, etc. etc. These all help me absorb peoples’ thoughts, attitudes, vocabulary and phrasing, as well as informing me first-hand about the way they lived.

Apart from the written legacy, the Regency has left us a rich legacy of images—paintings, portraits, engravings, cartoons, caricatures, fashion prints, book illustrations. I was amazed at the wealth of contemporary, hand-coloured engravings that can still be purchased at reasonable prices and that show rather than tell what Regency society was like. And finally, buildings, furniture and fittings, sculptures, gravestones and church and other monuments bear living witness to the past.

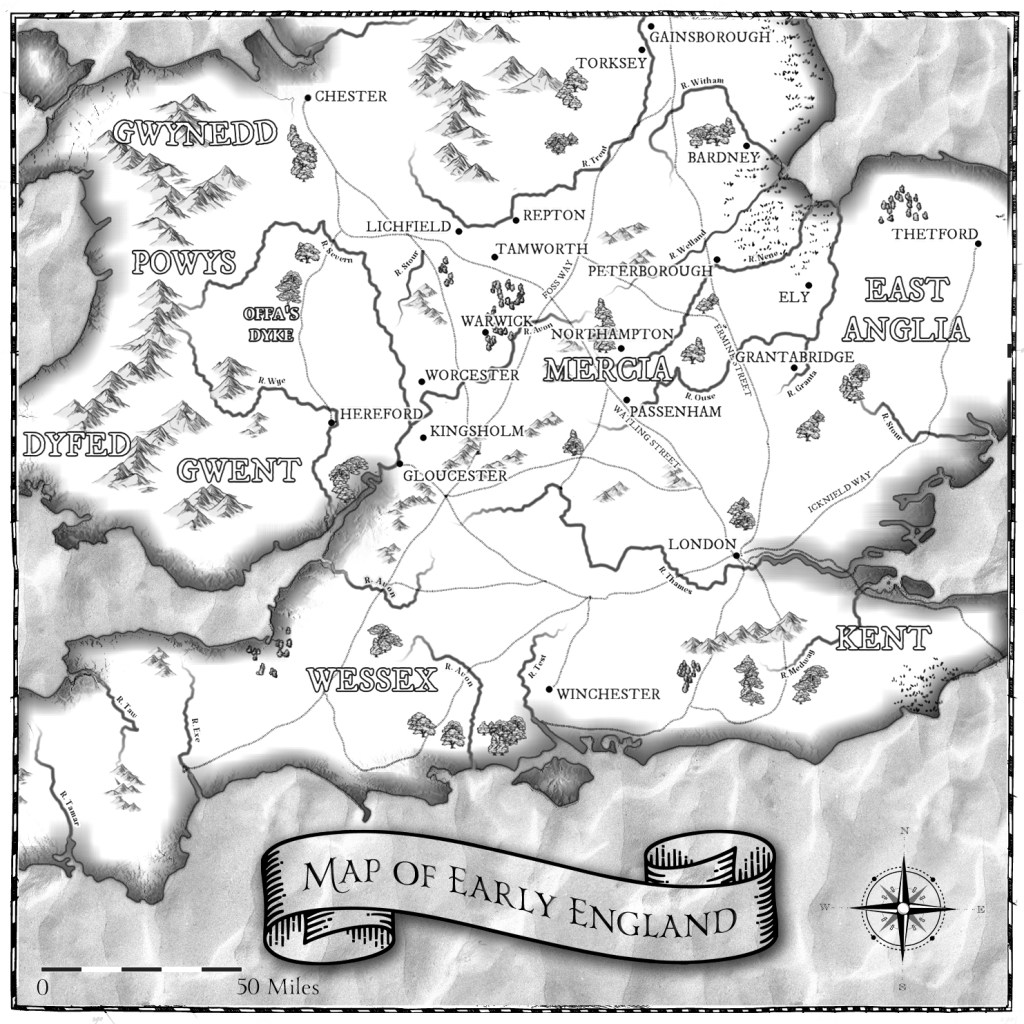

As an author, you must ask yourself constantly, if we do it this way today, how was it done in the past? You must read widely, covering every aspect of life at the time and take every opportunity to visit museums and period houses. Keep your eyes open everywhere you go to identify what was there then. I live in Dublin which is very much a Georgian city; I went to school in Georgian houses and later worked in many of them so you could say the city architecture of the time is in my bones. Remember too that then as now, older buildings will have co-existed with new one. Guidebooks from the period are very useful as they describe places as your characters will have seen them, and frequently have maps and other illustrations that will help you plan your character’s journeys.

All this is general research that feeds into your descriptive writing without your really being aware of it. Over and above this, there is the particular research that every new work calls for. The very first thing I do is create a public time-line for the years in which a new book is set. Here I enter every date and event I find including those of Easter, university, school and law terms, parliamentary sessions, the queen’s drawing-rooms, theatre and concert dates, publication dates of new works, and any notable public events, scandals or anything else newsworthy. These are the things that shape my characters’ lives, that they talk about. They help add verisimilitude and also frequently inspire plot twists.

I start this research on the internet. Frequently I get the information I want there and sometimes it points me in the right direction e.g. to little known diaries that help me flesh out my narrative. In Lady Loring’s Dilemma, I wanted to base my main characters in Paris and Nice in 1814/15 and was delighted to discover the Diary of the Times of George the Fourth, published in 1838 by an anonymous lady who had been in Paris and Nice at just those times. Lady Loring’s Dilemma opens in Harrogate, a well-known spa at the time, and I was thrilled to find a contemporary guide to taking the waters there which included a description of the sights in the surrounding area.

Don’t be afraid to ask the experts. For The Husband Criteria, I discovered that the Royal Academy provides a lot of information online about the years the Academy was based at Somerset House where its annual exhibition was a highlight of the Season. When I needed further information, I emailed the RA and received a prompt and helpful reply from the librarian. Similarly, when I need details of the laws of Cricket in 1814 for A Suggestion of Scandal, a query to the Marylebone Cricket Club was answered immediately and in detail by their Research Officer.

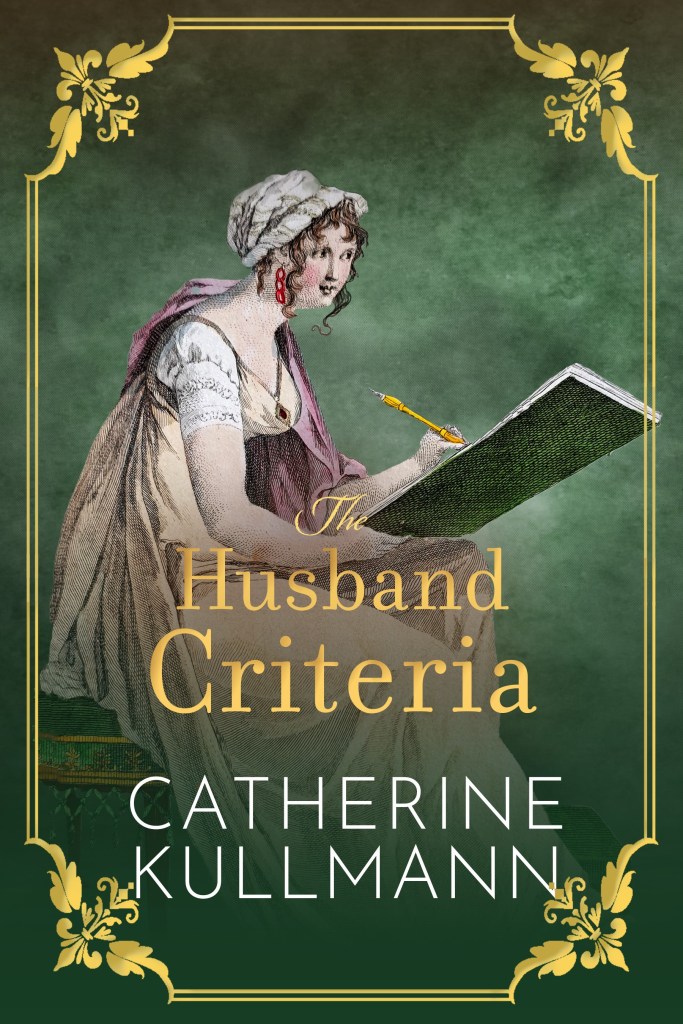

I trawl antique fairs, charity shops, second-hand book sales and flea markets for research material, whether it is books, newspapers, or old prints and engravings. As well as being a source of inspiration, I use antique prints and engravings from my collection for the covers of my books. This is generally cheaper than paying a licence fee for a stock image, it saves me hours of searching for just the right one and I have the freedom to use the image without restrictions.

All this sounds like a lot of work, but I love it. I started writing about the Regency because the period fascinates me and it still does. There is still so much to learn, I love the thrill of the hunt when I find just the right piece of trivia to spur me on.

© Catherine Kullmann 2023

Thank you so much for sharing. Good luck with your new book.

Here’s the blurb

London 1817

The primary aim of every young lady embarking on the Spring frenzy that is the Season must be to make a good match. Or must it? And what is a good match? For cousins Cynthia, Chloe and Ann, well aware that the society preux chevalier may prove to be a domestic tyrant, these are vital questions. How can they discover their suitors’ true character when all their encounters must be confined to the highly ritualised round of balls, parties and drives in the park?

As they define and refine their Husband Criteria, Cynthia finds herself unwillingly attracted to aloof Rafe Marfield, heir to an earldom, while Chloe is pleased to find that Thomas Musgrave, the vicar’s son from home, is also in London. And Ann must decide what is more important to her, music or marriage.

And what of the gentlemen who consider the marriage mart to be their hunting grounds? How will they react if they realise how rigorously they are being assessed?

A light-hearted, entertaining look behind the scenes of a Season that takes a different course with unexpected consequences for all concerned.

Buy Links:

Meet the author

Catherine Kullmann was born and educated in Dublin. Following a three-year courtship conducted mostly by letter, she moved to Germany where she lived for twenty-five years before returning to Ireland. She has worked in the Irish and New Zealand public services and in the private sector. Widowed, she has three adult sons and two grandchildren.

Catherine has always been interested in the extended Regency period, a time when the foundations of our modern world were laid. She loves writing and is particularly interested in what happens after the first happy end—how life goes on for the protagonists and sometimes catches up with them. Her books are set against a background of the offstage, Napoleonic wars and consider in particular the situation of women trapped in a patriarchal society.

She is the author of The Murmur of Masks, Perception & Illusion, A Suggestion of Scandal, The Duke’s Regret, The Potential for Love, A Comfortable Alliance and Lady Loring’s Dilemma.

Catherine also blogs about historical facts and trivia related to this era. You can find out more about her books and read her blog (My Scrap Album) at her website. You can contact her via her Facebook page or on Twitter.

Author Links

Book Bub: Amazon Author Page: Goodreads: