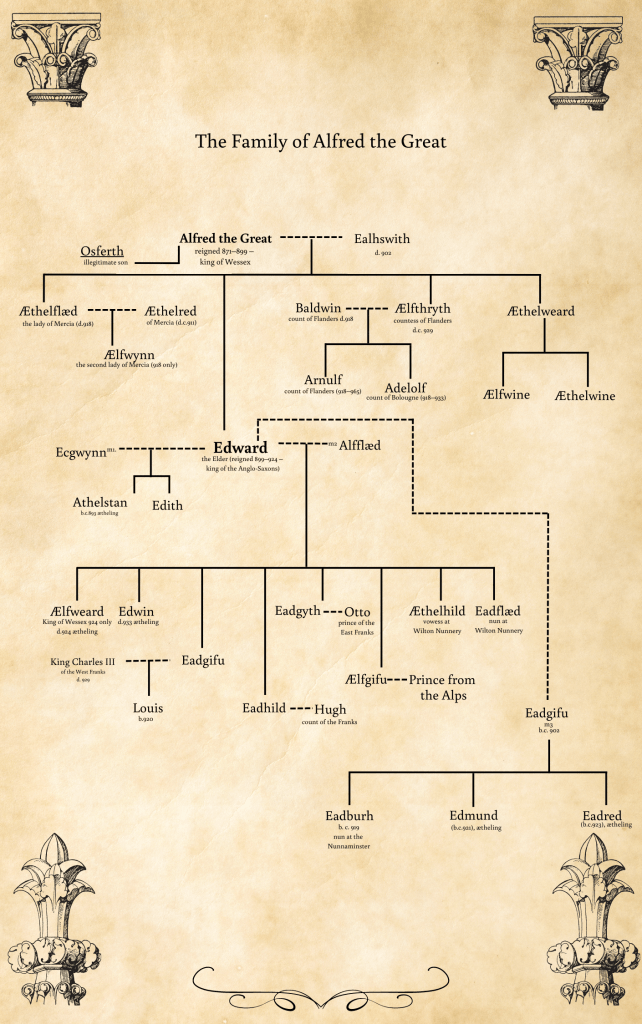

Ælfwynn, the daughter of Æthelflæd of Mercia and her husband, Æthelred was born at some point in the late 880s or early 890s. It’s believed that she was an only child, although it does appear (in the later accounts of William of Malmesbury – an Anglo-Norman writer from centuries later) that her cousins, Athelstan, and his unnamed sister, were sent to Mercia to be raised by their aunt when Edward remarried on becoming king in 899. There is a suggestion that it might have been Alfred’s decision to do this and that Athelstan was being groomed to become king of Mercia, not Wessex.

Ælfwynn is mentioned in three charters. S367, surviving in one manuscript, dates to 903, where she witnesses without a title. S1280, survives in two manuscripts, dates to 904 and reads in translation.

‘Wærferth, bishop, and the community at Worcester, to Æthelred and Æthelflæd, their lords; lease, for their lives and that of Ælfwynn, their daughter, of a messuage (haga) in Worcester and land at Barbourne in North Claines, Worcs., with reversion to the bishop. Bounds of appurtentant meadow west of the [River] Severn.’[i]

[i] Sawyer, P. H. (Ed.), Anglo-Saxon charters: An annotated list and bibliography, rev. Kelly, S. E., Rushforth, R., (2022). http://www.esawyer.org.uk/ S1280. See above for the full details under Æthelflæd

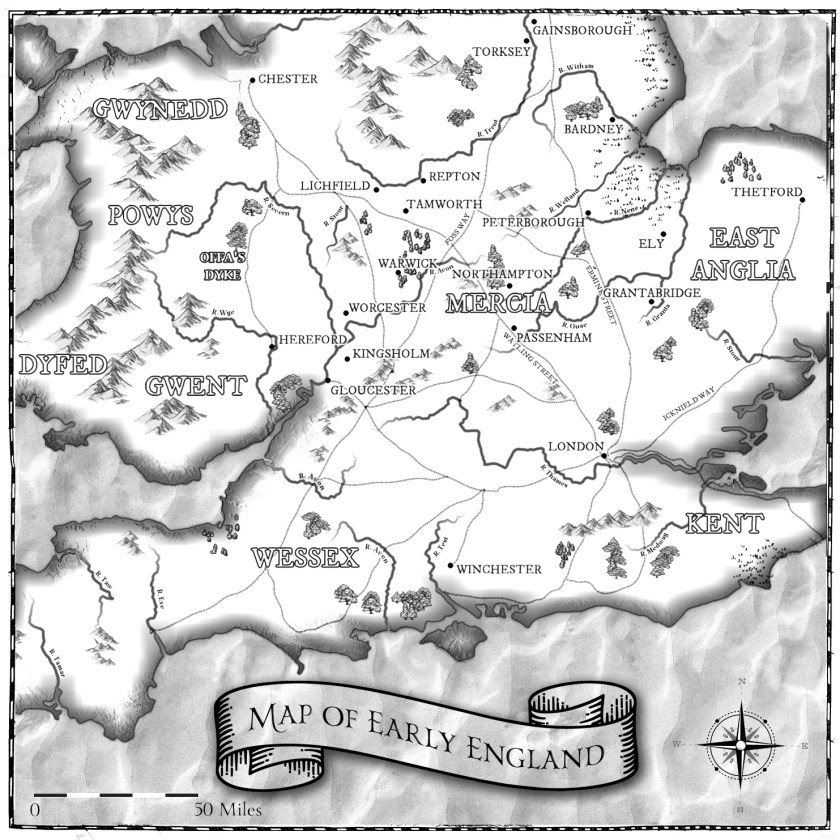

Historians have reconstructed this haga in Worcester in ‘The city of Worcester in the tenth century’ by N Baker and R Holt.

In S225, surviving in one manuscript, dated to 915, Ælfwynn witnesses below her mother. Hers is the second name on the document. This could be significant, as she would certainly have been an adult by now, was she already being prepared as the heir to Mercia on her mother’s death?

Ælfwynn is named in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the C text under 919. ‘Here also the daughter of Æthelred lord of the Mercians, was deprived of all control in Mercia, and was led into Wessex three weeks before Christmas; she was called Ælfwynn.’[i]

[i] Swanton, M. trans and edit The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (Orion Publishing Group, 2000), p.105

And from there, we hear nothing more of Lady Ælfwynn, the second lady of the Mercians. Even though this is the first record of a ruling woman being succeeded by her daughter.

There’s no further mention of Ælfwynn in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. It’s been assumed that she became a nun, and she might well be referenced in charter S535, surviving in one manuscript, and which Eadred granted at the request of his mother, dated to 948, reading,

‘King Eadred to Ælfwyn, a religious woman; grant of 6 hides (mansae), equated with 6 sulungs, at Wickhambreux, Kent, in return for 2 pounds of purest gold.’[i]

[i] Sawyer, P. H. (Ed.), Anglo-Saxon charters: An annotated list and bibliography, rev. Kelly, S. E., Rushforth, R., (2022). http://www.esawyer.org.uk/ S535

Bailey has suggested that, ‘In view of its close association with the women of the royal family, and of Eadgifu’s patronage of Ælfwynn (in S535), I would venture to suggest that it is possible she too may have ended her days at Wilton.’[i]

[i] Bailey. M, ‘Ælfwynn, Second Lady of the Mercians’, Edward the Elder, 899-924 Higham, N.J. and Hill, D. H. ed (Routledge, 2001), p.125

This would mean that rather than ruling as her mother would have wanted her to, Ælfwynn was overruled by her uncle, who essentially stole her right to rule Mercia as soon as he possibly could on her mother’s death. It must be said that he might have later paid for this with his life if he was indeed putting down a Mercian rebellion in Farndon when he died in 924.

Alternatively, there is another beguiling theory that Ælfwynn might not have become a nun but was, in fact, married to Athelstan, an ealdorman of East Anglia, known as the ‘Half-King,’ because of the vast control he had in East Anglia. It’s long been believed that this label might well have resulted from the fact that Athelstan was an extremely powerful and well-landed nobleman who was much beloved by the Wessex royal family and its kings. However, it might well be because he was indeed married to the king’s cousin (under Athelstan, Edmund and Eadred). If this is the case, and it’s impossible to prove, then Ælfwynn, as the wife of Ealdorman Athelstan, had four sons, Æthelwold, Æthelwine, Æthelsige and Ælfwold, and these sons would be friends and enemies of the kings of England in later years. She might also have been given the fostering of the orphaned, and future King Edgar, which would also have made these men the future king’s foster brothers.

‘he [Athelstan Half-King] bestowed marriage upon a wife, one Ælfwynn by name, suitable for his marriage bed as much as by the nobility of her birth as by the grace of her unchurlish appearance. Afterwards she nursed and brought up with maternal devotion the glorious King Edgar, a tender boy as yet in the cradle. When Edgar afterwards attained the rule of all England, which was due to him by hereditary destiny, he was not ungrateful for the benefits he had received from his nurse. He bestowed on her, with regal munificence, the manor of Weston, which her son, the Ealdorman, afterwards granted to the church of Ramsey in perpetual alms for her soul, when his mother was taken from our midst in the natural course of events.’

Edington, S and Others, Ramsey Abbey’s Book of Benefactors Part One: The Abbey’s Foundation, (Hakedes, 1998) pp.9-10

If this identification is correct, ‘This would explain why she was considered suitable to be a foster-mother to the ætheling Edgar. It may even explain why Edgar was considered in 957 suitable to rule Mercia.’[i]

[i] Jayakumar, S. ‘Eadwig and Edgar’, in Edgar, King of the English, 959-975, ed. D Scragg (Boydell Press, 2014), p.94

If Lady Ælfwynn did survive beyond the events of 919, it seems highly likely she would have continued her friendship with her cousin, Athelstan, when he became king of Mercia, and then Wessex and then England. It’s also highly likely that she might have rallied support for him in Mercia.

Certainly, the first known occurrence of a woman succeeding a woman in Saxon England ended in obscurity for Lady Ælfwynn.

So, who is my Lady Ælfwynn?

Well, she’s a warrior woman, reeling from the unexpected death of her mother. She is her mother’s daughter. She knows what’s expected of her, and she has no problem contending with the men of the witan, her uncle, Edward king of Wessex, or indeed, the Viking raiders. She and Rognvaldr Sigfrodrsson have a particularly intriguing relationship.

Here’s the beginning of The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter

‘The men of the witan stand before me in my hall at Tamworth, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Mercia. The aged oak beams bear the brunt of centuries of smoking fires. Some are hard men, glaring at me as though this predicament is of my making. They are the beleaguered Mercians, the men from the disputed borders to the north, the east, and the west, if not the south. They’re the men who know the cost of my mother’s unexpected death. And strangely, for all their hard stares and uncompromising attitudes, their crossed arms and tight shoulders, they’re the men I trust the most in this vast hall. It’s filled with people I know by name and reputation, if not by sight.

Those with sympathy etched onto their faces are my uncle’s allies. These men might once have understood the dangers that Mercia faces, but they’ve grown too comfortable hidden away in Wessex and Kent. Mercia has suffered the brunt of the continual encroachments while they’ve been safe from Viking attack for nearly twenty years. Some are too young to have been born when Wessex was almost extinguished under the onslaught of the northern warriors.

Even the clothes of the sympathetic are different from those with hard stares. Not for them, the warriors’ garb. There are no gaping spaces on warrior belts where seaxes and swords should hang, but don’t, as weapons must not be worn in my presence.

No, they wear the luxurious clothing of royalty, even if they’re not members of the House of Wessex. They have the time, and the wealth, to ensure their attire is as opulent as it can be. They don’t fear a middle-of-the-night call to arms. They don’t need to maintain vigilance or continuously be battle-ready. They don’t have to fight for their kingdom and their family at a moment’s notice or be ready to lose a loved one or face a fight to the death.’

(available with Kindle Unlimited)