Another book birthday

I feel like these are coming thick and fast this year, but then I suppose I’ve written a lot of books.

To celebrate The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter turning 8, yes 8, today, I thought I’d share why I wrote about Lady Ælfwynn, and not her more famous mother, Lady Æthelflæd.

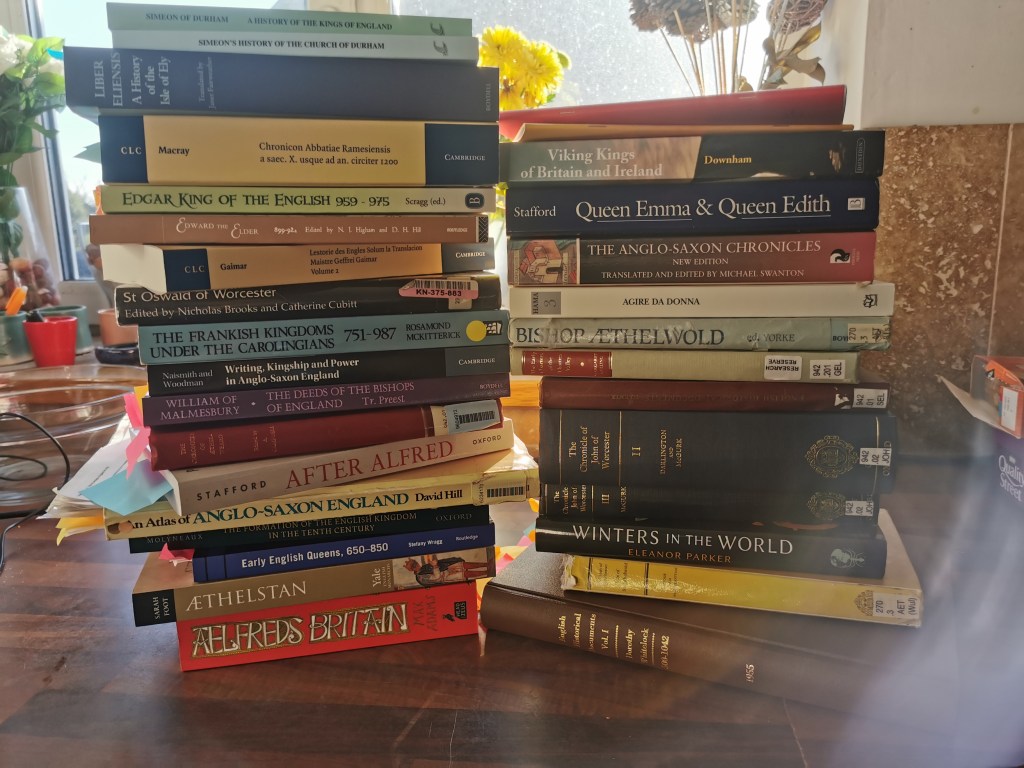

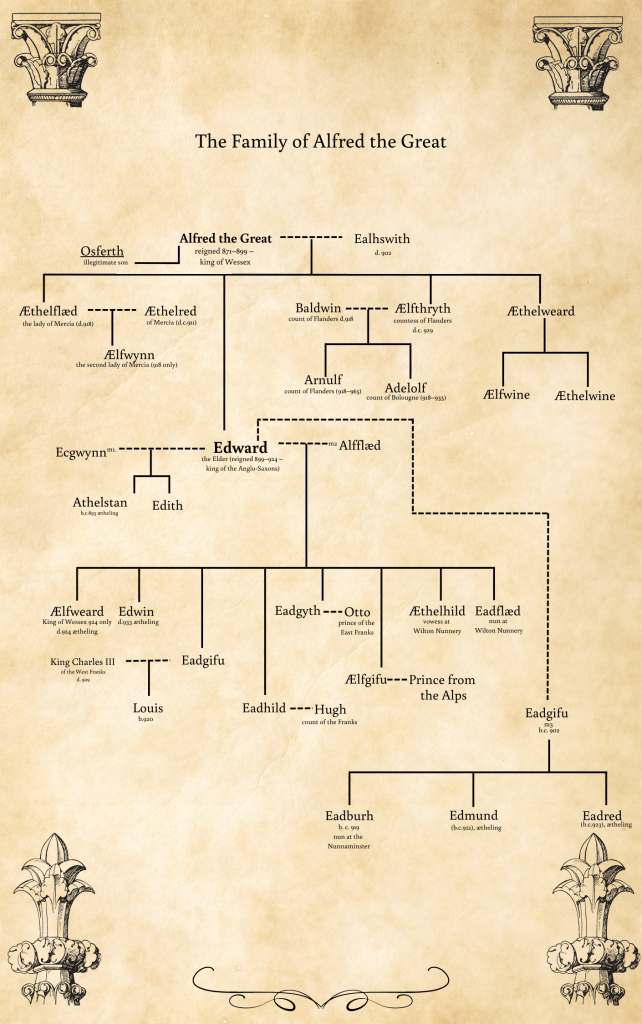

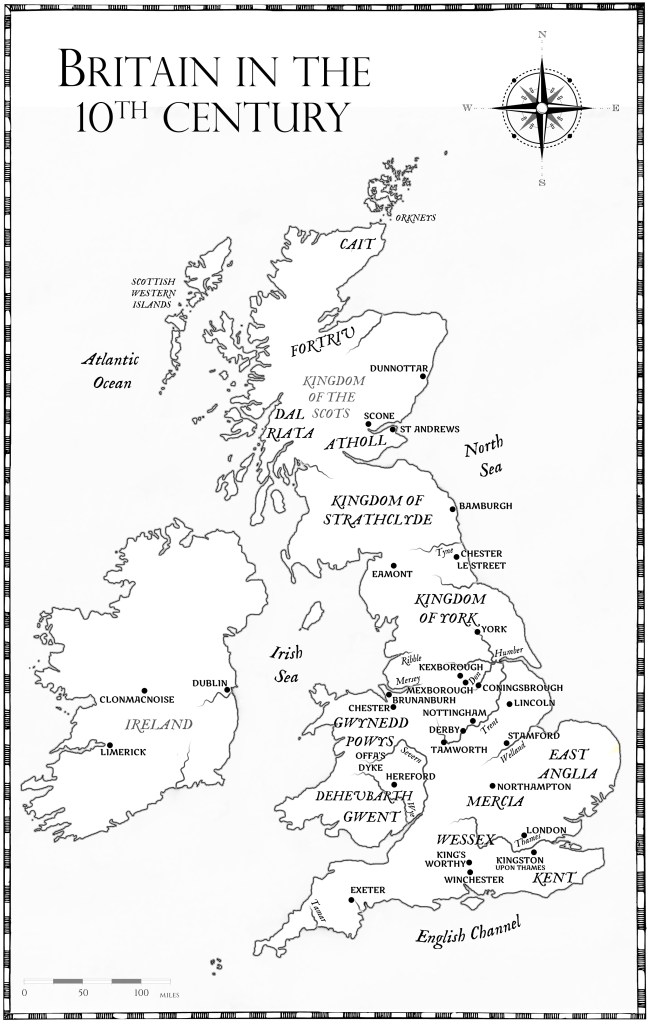

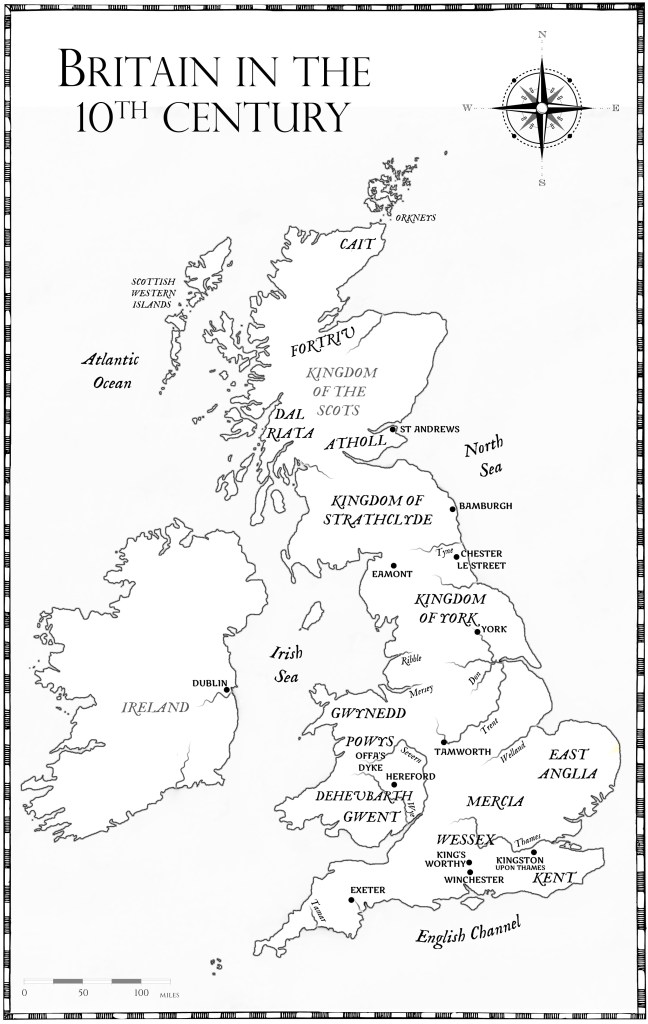

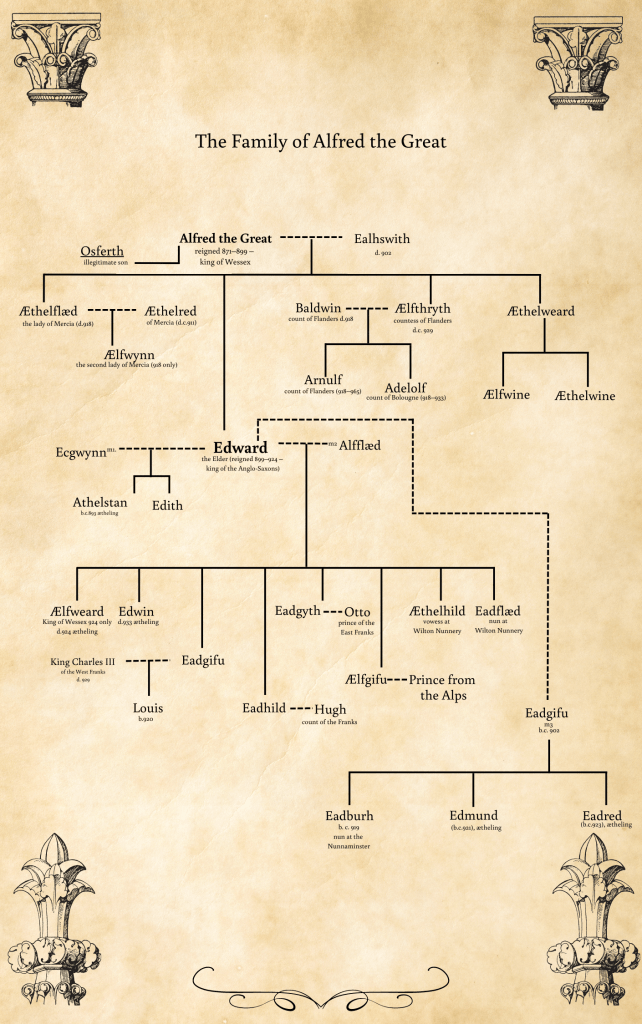

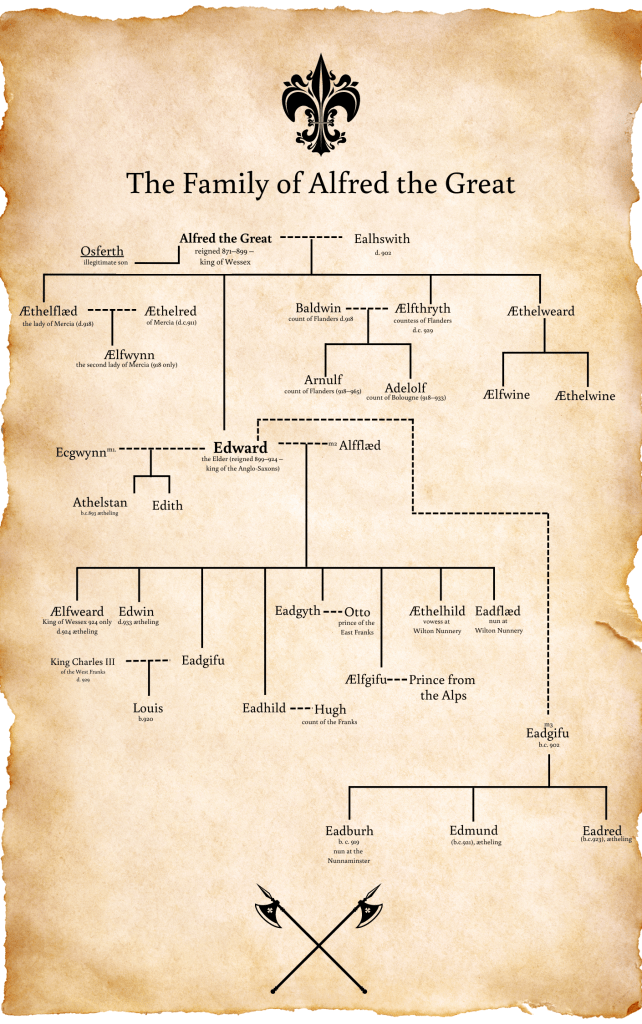

My first historical fiction story (that of Ealdorman Leofwine) was inspired by the fact that I realised he’d been almost written out of the history of the period. I’d read many, many books about the end of Saxon England, and few of them mentioned the Earls of Mercia at all, apart from his descendants, Edwin, Morcar and Eadgyth. This has often been the way. I find a character who’s been forgotten about (because most historical individuals have been forgotten about) and I reimagine their lives and endeavour to either rehabilitate them, or at least shine a light on them. The same can be said for Lady Ælfwynn, the Lady of Mercia’s Daughter, and the Second Lady of the Mercians in her own right.

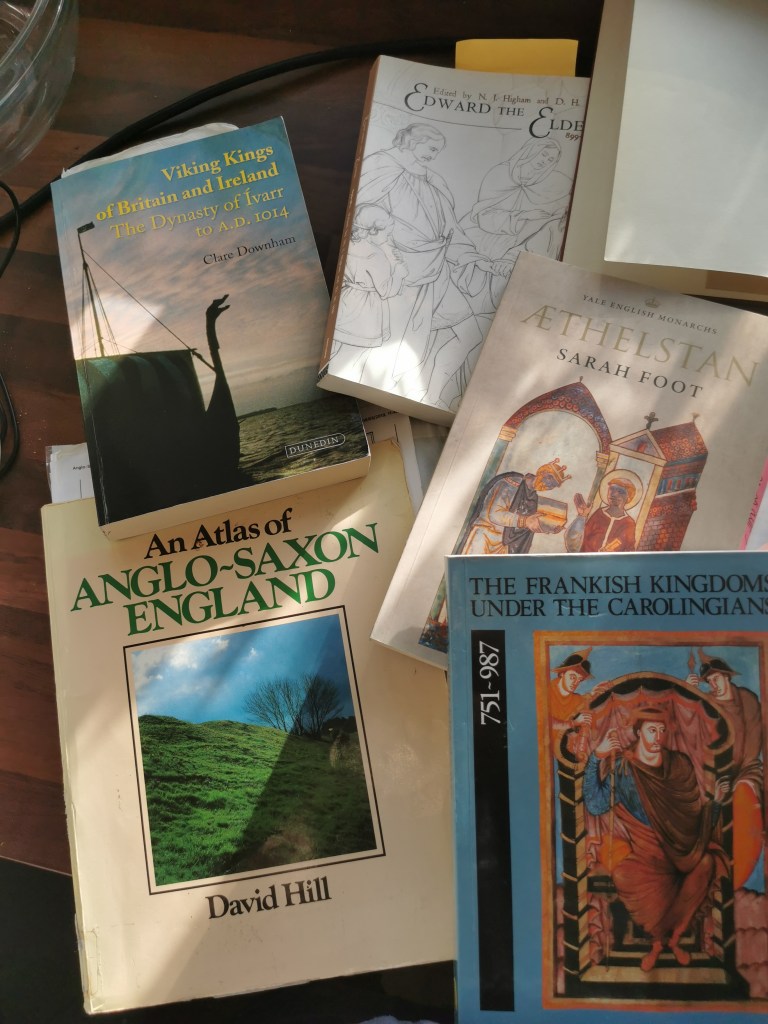

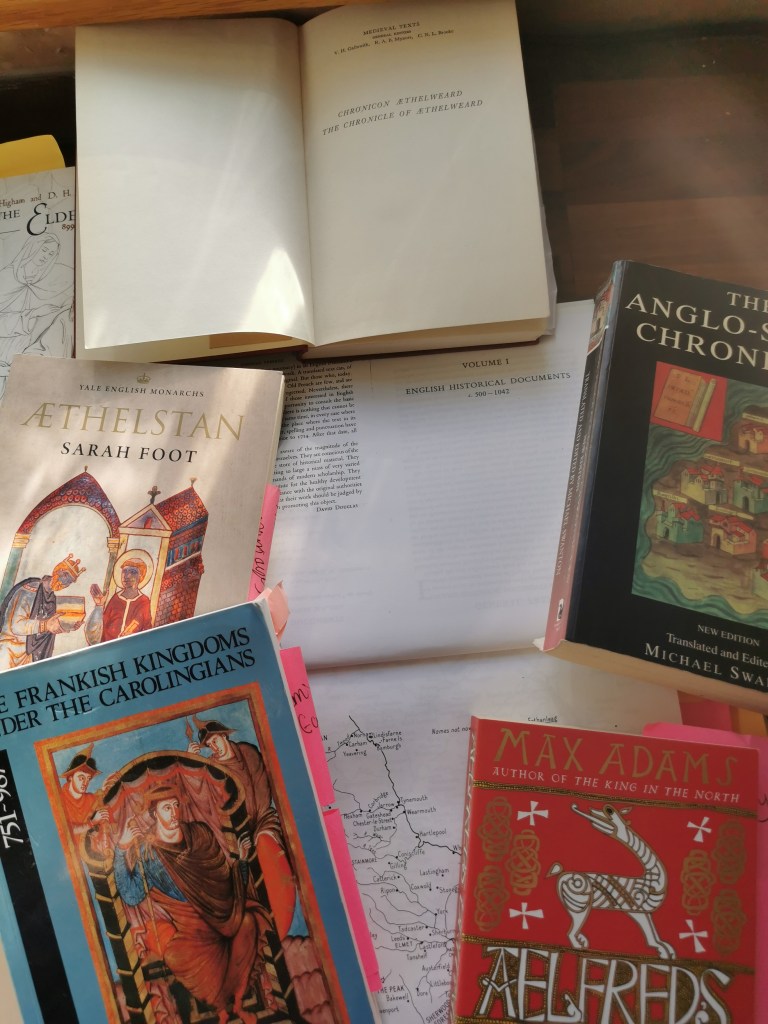

Even though she attests a number of charters, and is named in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (which is very rare for the women of the tenth century) no one had heard of her. I was determined to put that right, largely helped by an academic paper I read about her which got my brain firing with ideas.

Piecing together the scant information available (and possibly known) about her, I created The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter, and subsequently, the sequel, A Conspiracy of Kings. In doing so I don’t suggest at all that this is a recreation of the life she led, but it certainly presents a possible life for her, and one that is a little more exciting than the often cited ‘she became a nun,’ argument to explain why she disappears from the historical record so quickly. It also allowed me to try my hand at family politics, which so often came into play during the era. And, for fans of King Coelwulf II and The Last King books, I can certainly ‘see’ a lot of his later creation in the pages of The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter.

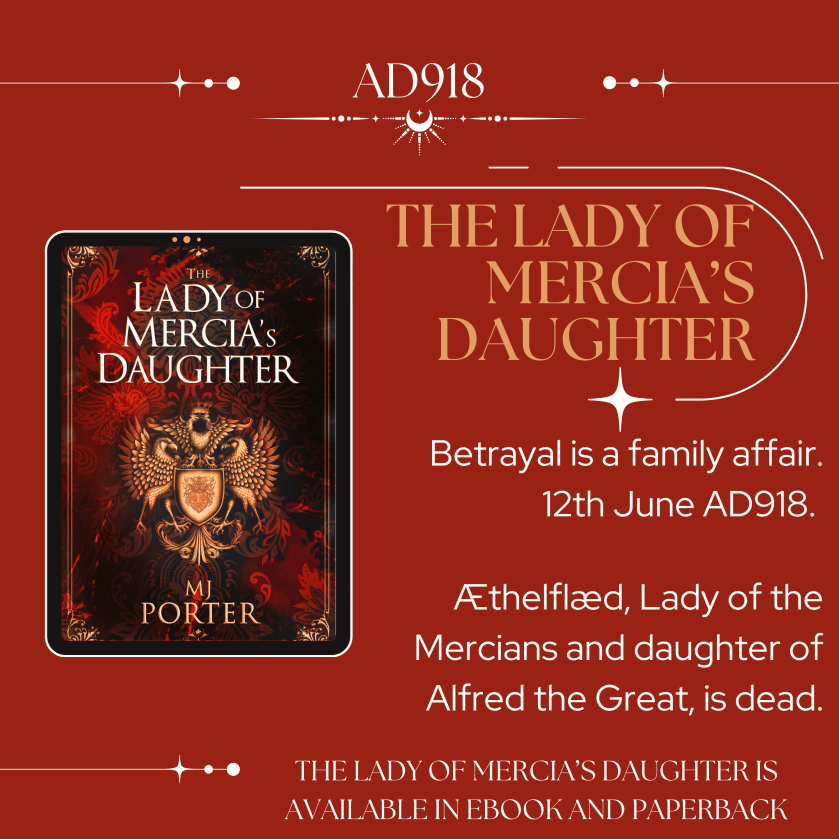

Here’s the blurb

Betrayal is a family affair.

12th June AD918.

Æthelflæd, Lady of the Mercians and daughter of Alfred the Great, is dead.

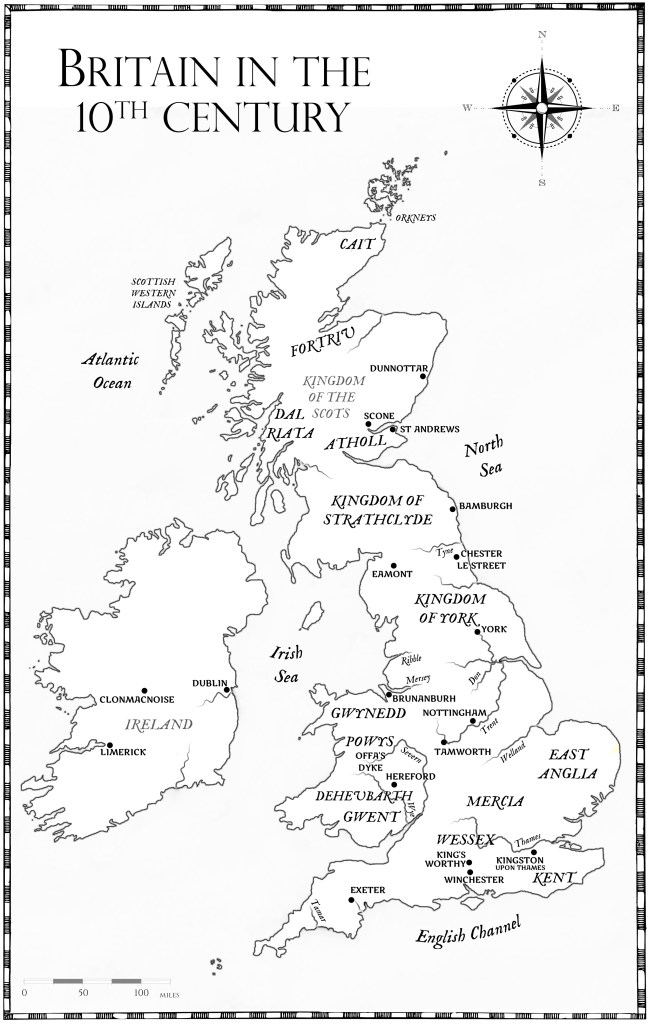

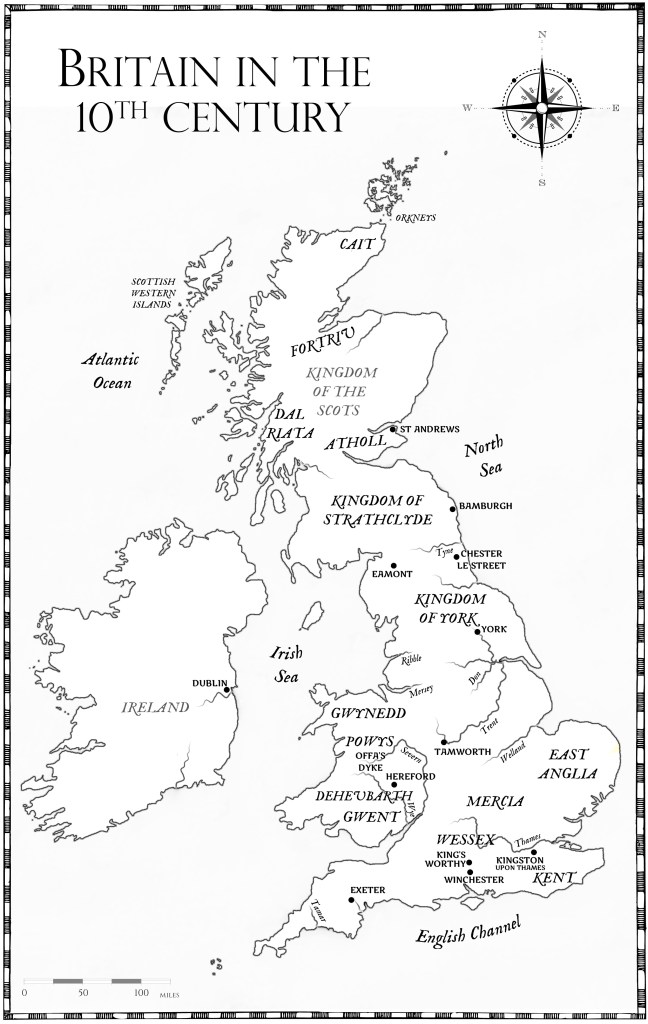

Ælfwynn, the niece of Edward, King of Wessex, has been bequeathed her mother’s power and status by the men of the Mercian witan. But she knows Mercia is vulnerable to the north, exposed to the retreating world of the Viking raiders from her mother’s generation.

With her cousin Athelstan, Ealdorman Æthelfrith and his sons, Archbishop Plegmund and her band of trusted warriors, Ælfwynn must act decisively to subvert the threat from the Norse. Led by Lord Rognavaldr, the grandson of the infamous Viking raider, Ivarr of Dublin, they’ve turned their gaze toward the desolate lands of northern Saxon England and the jewel of York.

Inexplicably she’s also exposed to the south, where her detested cousin, Ælfweard, and uncle, King Edward, eye her position covetously, their ambitions clear to see.

This is the unknown story of Ælfwynn, the daughter of the Lady of the Mercians and the startling events of late 918 when family loyalty and betrayal marched hand in hand across lands only recently reclaimed by the Mercians. Kingdoms could be won or lost through treachery and fidelity, and there was little love and even less honesty. And the words of a sword were heard far more loudly than those of a king or churchman, noble lady’s daughter or Viking raider.

You can now grab The Lady of Mercia’s Daughter duology, containing both books featuring Lady Ælfwynn

Check out the series page for The Tenth Century Royal Women.