On the 27th October 939, the death of Athelstan, the first king of the English, at Gloucester. The symmetry of the death of King Athelstan and King Alfred, his grandfather, is noted in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle A text, ‘40 years all but a day after King Alfred passed away’.[i]

[i] Swanton, M. ed. and trans. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (Orion Publishing Group, 2000), p.110

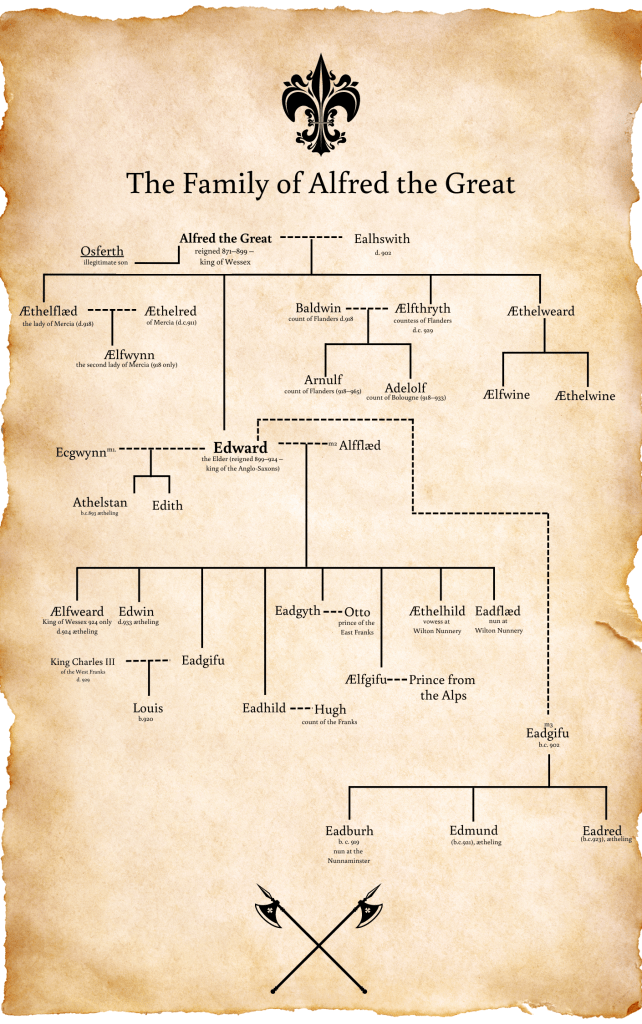

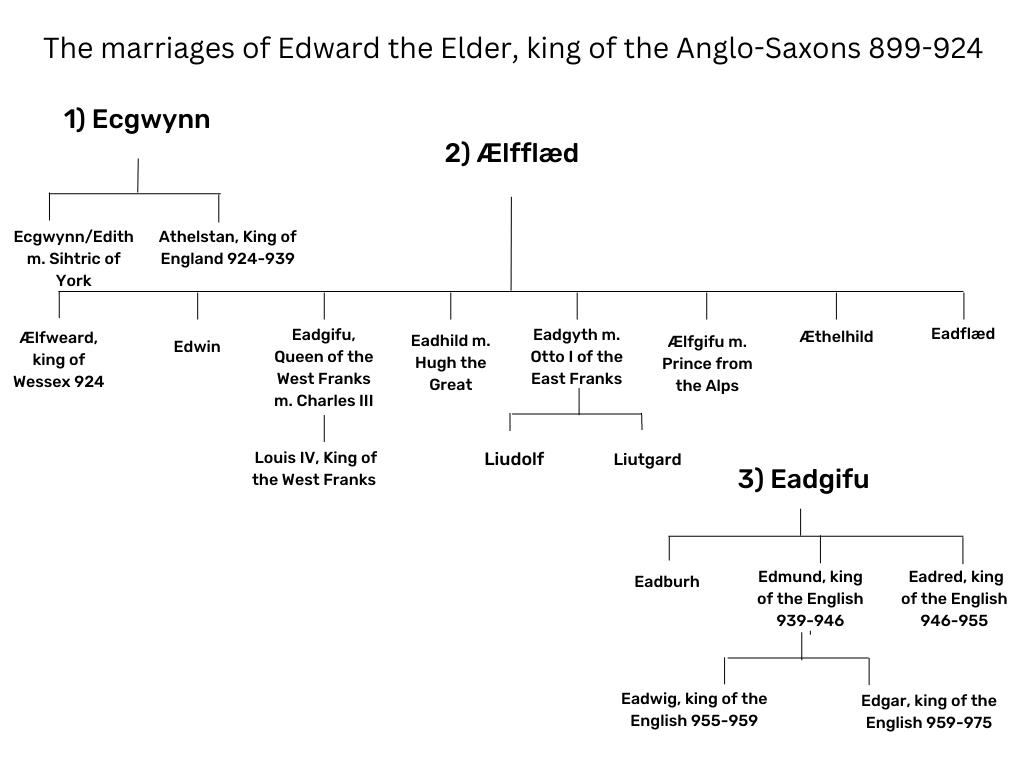

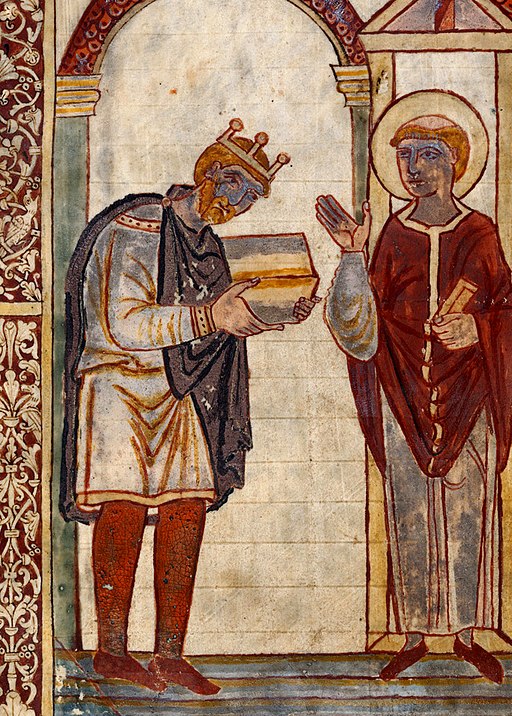

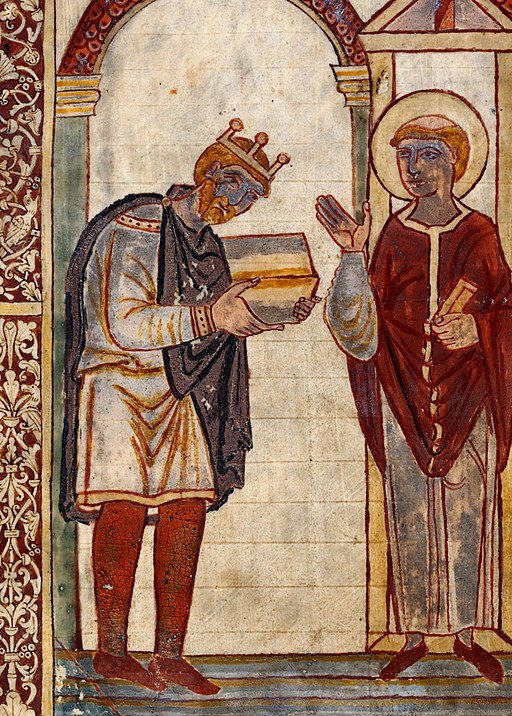

We don’t know for sure who Athelstan’s mother was, it’s believed she might have been called Ecgwynn. We don’t know, for certain, the name of his full sister, but it’s believed she might have been named Edith or Ecgwynn after her mother. What is known is that his father was Edward, the son of King Alfred, and known to us today as Edward the Elder. Athelstan is rare in that he is one of only two Saxon kings for whom a contemporary image is available. (The other is Edgar, who would have been his nephew)

It must be supposed that Athelstan was born sometime in the late 890s. And according to a later source written by William of Malmesbury in the 1100s (so over two hundred years later), was raised at the court of his aunt, Æthelflæd of Mercia. David Dumville has questioned the truth of this, but to many, this has simply become accepted as fact.

‘he [Alfred] arranged for the boy’s education at the court of his daughter, Æthelflæd and Æthelred his son in law, where he was brought up with great care by his aunt and the eminent ealdorman for the throne that seemed to await him.’[i]

[i] Mynors, R.A.B. ed and trans, completed by Thomson, R.M. and Winterbottom, M. Gesta Regvm Anglorvm, The History of the English Kings, William of Malmesbury, (Clarendon Press, 1998), p.211 Book II.133

Why then might this have happened? Edward became king on the death of his father, Alfred, and either remarried at that time, or just before. Edward’s second wife (if indeed, he was actually married to Athelstan’s mother, which again, some doubt), Lady Ælfflæd is believed to have been the daughter of an ealdorman and produced a hefty number of children for Edward. Perhaps then, Athelstan and his unnamed sister, were an unwelcome reminder of the king’s first wife, or perhaps, as has been suggested, Alfred intended for Athelstan to succeed in Mercia after the death of Æthelflæd, and her husband, Æthelred, for that union produced one child, a daughter named Ælfwynn.

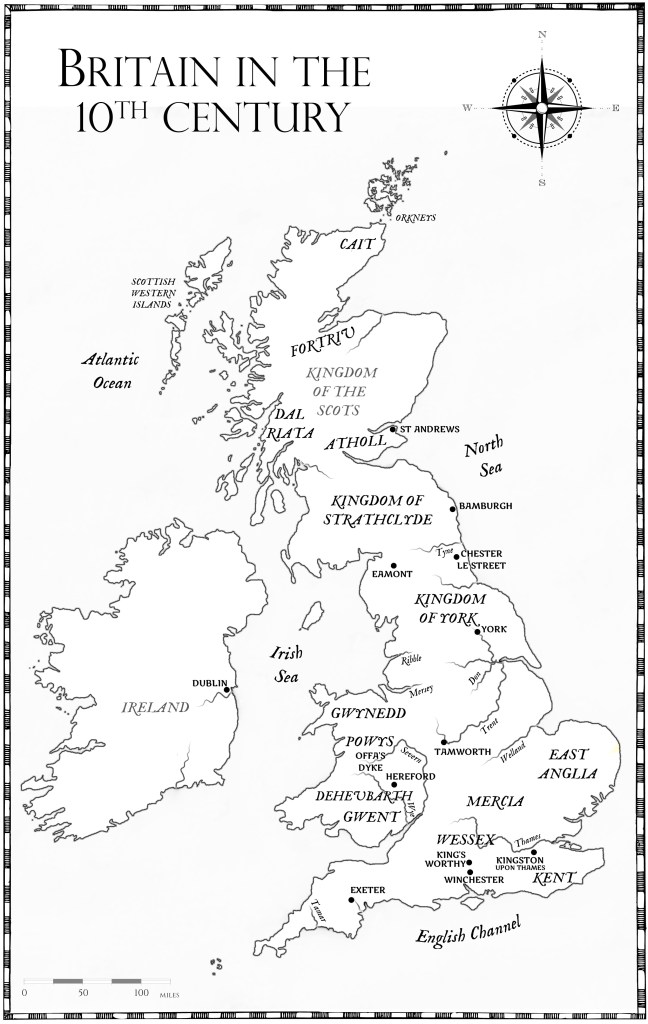

What is known is that following the death of King Edward in 924, Athelstan was acknowledged as the king of Mercia; his half-brother, Ælfweard was proclaimed king in Wessex for a very short period.

‘Here King Edward died at Farndon in Mercia; and very soon, 16 days after, his son Ælfweard died at Oxford; and their bodies lie at Winchester. And Athelstan was chosen as king by the Mercians and consecrated at Kingston.’[i]

[i] Swanton, M. trans and edit The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, (Orion Publishing Group, 2000), D text p.105

But Ælfweard’s reign was short-lived and Athelstan was eventually proclaimed king of Wessex, as well as Mercia, and then, in time, as the king of the English, although his acceptance by the Wessex witan has been seen as very grudgingly given.

Whatever the exact details of the beginning of his kingship, Athelstan was consecrated in September 925, and the words of the ceremony are believed to survive (there is an argument as to whether the ceremony was written for his father or for him), and during the ceremony Athelstan was proclaimed as king not with the placement of a warrior helm on his head, but instead, with a crown, the first known occurrence of this in England.

Here’s my reimagining of the ceremony in King of Kings,

Athelstan, Kingston upon Thames, September AD925

‘This means that only a year after my father’s untimely death, the kingdoms of Mercia, those parts of the East Anglian kingdom that my father lately reclaimed, Wessex and Kent, are reunited again under one ruler. The Saxons, or rather, the English, have just one king. And this is my moment of divine glory, when, before the men and women of the Mercian and Wessex witan, I’ll be proclaimed as king over all.

A prayer is intoned by the archbishop of Canterbury, Athelm, appealing to God to endow me with the qualities of the Old Testament kings: Abraham, Moses, Joshua, David and Solomon. As such, I must be faithful, meek, and full of fortitude and humility while also possessing wisdom. I hope I’ll live up to these lofty expectations.

I’m anointed with the holy oil and then given a thick gold ring with a flashing ruby to prove that I accept my role as protector of the one true faith. A finely balanced sword is placed in my hands, the work of a master blacksmith, with which I’m to defend widows and orphans and through which I can restore things left desolated by my foes, and my foes are the Norse.

Further, I’m given a golden sceptre, fashioned from gold as mellow as the sunset, with which to protect the Holy Church, and a silver rod to help me understand how to soothe the righteous and terrify the reprobate, help any who stray from the Church’s teachings and welcome back any who have fallen outside the laws of the Church.

With each item added to my person, I feel the weight of kingship settle on me more fully. I may have been the king of Mercia for over a year now, the king of Wessex and Kent for slightly less time, but this is the confirmation of all I’ve done before and all I’ll be in the future.

It’s a responsibility I’m gratified to take, but a responsibility all the same. From this day forward, every decision I make, no matter how trivial, will impact someone I now rule over.

*******

And I? I’m the king, as my archbishop, Athelm of Canterbury, proclaims to rousing cheers from all within the heavily decorated church at Kingston upon Thames, a place just inside the boundaries of Wessex but not far from Mercia. It’s festooned with bright flowers and all the wealth this church owns. Gold and silver glitter from every recess, reflecting the glow of the hundreds of candles.

I’m more than my father, Edward, was and I’m more than my grandfather, Alfred, was. I’m the king of a people, not a petty kingdom, or two petty kingdoms, with Kent and the kingdom of the East Angles attached.

It’s done. I’m the anointed king of the English, the first to own such a title. I’ll protect my united kingdom, and with God’s wishes, I’ll extend its boundaries yet further, clawing back the land from the Five Boroughs and bringing the kingdom of the Northumbrians, and even the independent realm of Bamburgh, under my command.’

And Athelstan’s life is one of vast events. His reach extended far beyond the confines of England, or even the British Isles, his step-sisters making political unions in East and West Frankia, and his nephew becoming king of the West Franks. But he is perhaps best known for his victory at Brunanburh, over a coalition of the Scots and the Dublin Norse, and it is the tale of this great battle, and the events both before and afterwards, that I retell in the Brunanburh Series.

His death, on 27th October 939, can arguably be stated to have reset the gains made after Brunanburh, and set the creation of ‘England’ back, as his much younger step-brother battled to hold onto his brother’s gains, but for now, it is Athelstan and his triumphs which much be remembered, and not what happened after his untimely death.

Check out my Brunanburh series page for more information about Athelstan, and his fellow kings.