I don’t really know when I became a fan of historical fiction but I can take a good guess at who, and what, was to blame.

William Shakespeare and Macbeth.

When I was at school, we didn’t get ‘bogged’ down with grammar and spelling in English lessons, oh no, we studied stories, plays, words, and also the ‘motivation’ behind the use of those stories and those words. And it was Macbeth that first opened my eyes to the world of historical fiction.

Yes, Macbeth is a blood thirsty play, and it might be cursed, but more importantly, it’s based on Holinshed’s Chronicle of England, Scotland and Ireland.

Macbeth is nothing better than the first work of historical fiction that I truly read, and understood to be as such. And what a delight it was.

I remember less the story of Macbeth as presented by Shakespeare (aside from the three witches – “when shall we three meet again?” “well I can do next Wednesday,’ (thank you Terry Pratchett for that addition), than working out ‘fact’ from ‘fiction’ in his retelling of the story. And hence, my love of historical fiction was slowly born, and from that, stems my love of telling stories about ‘real’ people and the way that they lived their lives, looking at the wider events taking place, and trying to decide how these might, or might not, have influenced these people.

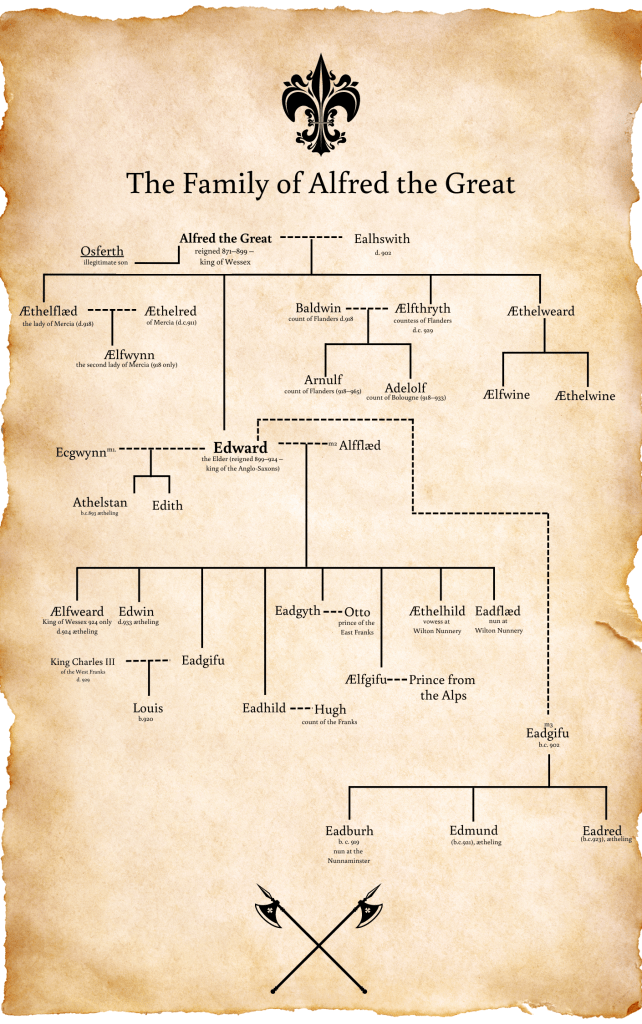

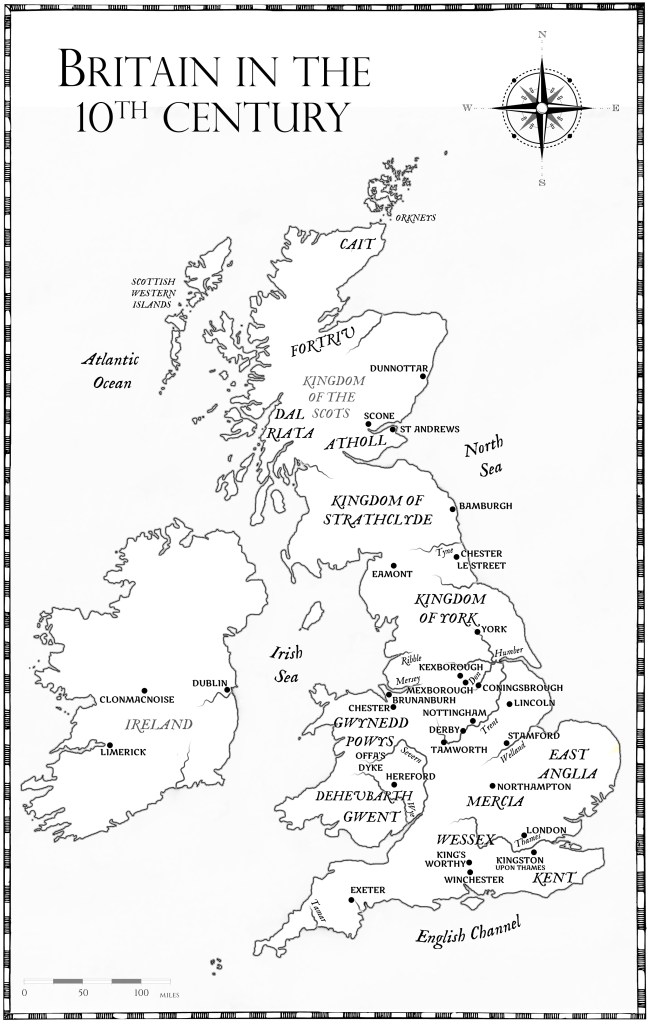

Shakespeare chose the story of a little-known ‘Scottish’ monarch for his historical fiction; my latest subject is the third wife of King Edward the Elder, again someone that few people have heard of, but whose relative, many years in the future, would have interacted with Macbeth, or rather with Mac Bethad mac Findlaích.

Lady Eadgifu, the Lady of Wessex, lived through a tumultuous time.

Many people studying Saxon England know of King Alfred (died AD899), and they know of his grandson, Æthelred II (born c.AD 968), known as ‘the unready’. But the intervening period is little known about, and that is a true shame.

Lady Eadgifu, just about singlehandedly fills this gap. Born sometime before c.AD903 (at the latest), her death occurred in c.AD964/6. As such, she probably missed Alfred by up to 4 years, and her grandson, King Æthelred by about the same margin.

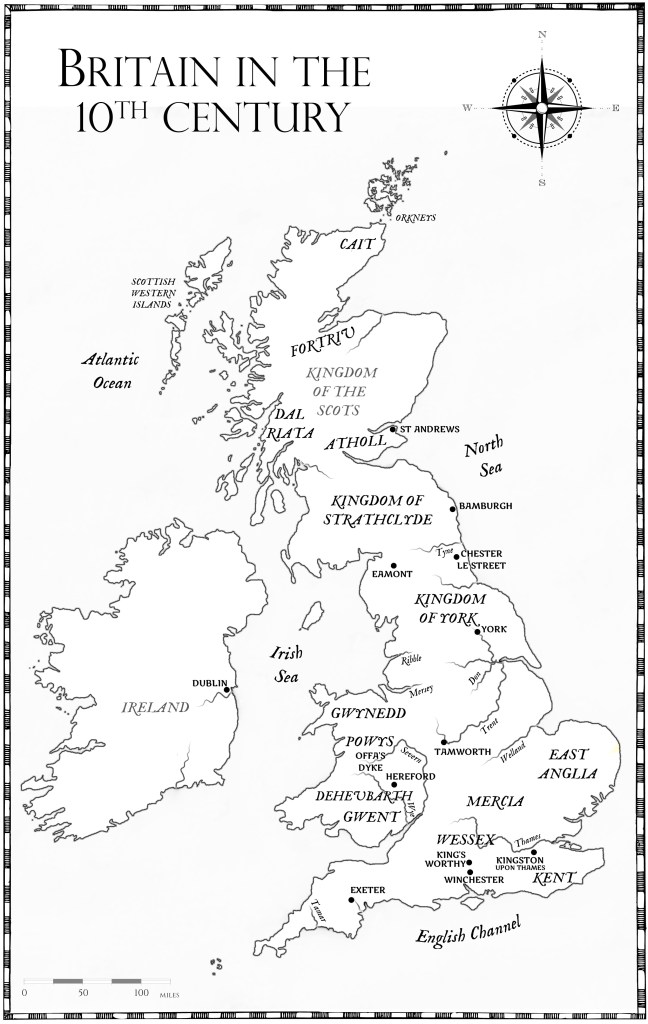

But what she did witness was the emergence of ‘England’ and the ‘kingdom of the English’ as we know it. And it wasn’t a smooth process, and it was not always assured, and it was certainly never, at any point, guaranteed that England would emerge ‘whole’ from the First Viking Age.

And more importantly, rather than being one of the kings who ruled during this period, Lady Eadgifu was the king’s wife, the king’s mother, or even the king’s grandmother. She would have witnessed England as it expanded and contracted, she would have known what went before, and she would have hoped for what would come after her life. (I think in this, I was very much aware of my great-grandmother who lived throughout almost the entire twentieth century – just think what she would have witnessed).

Lady Eadgifu was simply too good a character to allow to lie dormant under the one event that might well be known about from the tenth century – the battle of Brunanburh. She does also appear in my Brunanburh Series.

So, for those fans of Bernard Cornwell’s ‘Uhtred’ and for those fans of Lady Elfrida at the end of the tenth century, I hope you will enjoy Lady Eadgifu. She was a woman, in a man’s world, and because she was a woman, she survived when men did not.