Category: Pen and Sword Books

I’m delighted to share my review for Mary Tudor: The French Queen by Amy McElroy #non-fiction #TheTudors

Here’s the blurb

Mary Tudor, Henry VIII’s sister, lived a remarkable life. A princess, duchess and queen, she was known as the English Rose for her beauty. Mary Tudor, Queen of France, aims to explore the life of one of the few who stood up to Henry VIII and lived to tell the tale.

Henry VIII is well known, but his larger-than-life character often overshadows that of his sisters. Mary Tudor was born a princess, married a king and then a duke, and lived an extraordinary life. This book focuses on Mary’s life, her childhood, her relationship with Henry, her marriages and her relationship with her husbands.

Mary grew up in close proximity to Henry, becoming his favourite sister, and later, after her marriage to the French king, she married his best friend, Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk. The events impacting the siblings will be reviewed to examine how they may have changed and shaped their relationship.

Purchase Links

My Review

Mary Tudor by Amy McElroy is a fascinating biographical account of the life of Mary, Henry VIII’s sister, and not to be confused with his daughter.

The story is quite remarkable, and while I knew something about her, I didn’t know everything. The chapters, which follow her through the 3 marriage proposals she receives, which result in 2 marriages, are quite astounding. So much time and effort went into trying to wed her to Prince Charles (later Emperor Charles), and then all of a sudden, she married Louis XII of France. I found it most fascinating. If anything, her 2nd marriage seems almost anticlimatic, even though it evidently wasn’t at the time. And, with all we know about Henry and his marital difficulties, Mary appears to have been somewhat serene about everything. I imagine she perhaps had a happier life, if one often troubled by the terrible debt her brother placed upon her (families!).

I really appreciated the author’s desire to keep this narrative to Mary and not to her children and grandchildren. It seems fitting to have a title devoted exclusively to her.

A fine portrayal of Mary’s eventful, if short life, with a lovely writing style.

Meet the author

Amy was born and bred in Liverpool before moving to the Midlands to study criminal justice and eventually becoming a civil servant. She has long been interested in history, reading as much and as often as she could. Her writing journey began with her blog, sharing thoughts on books she had read before developing to writing reviews for Aspects of History. The Lives of Women in the Tudor Era is Amy’s second book. Her first, Educating the Tudors, focused on the educational opportunities of all classes, those who taught them and the pastimes enjoyed by all.

Mercia: Exploring the Heartland of Saxon England and Its Lasting Influence

Having written more books than I probably should about the Saxon kingdom of Mercia, and with more planned, I’ve somewhat belatedly realised I’ve never explained what Mercia actually was. I’m going to correct that now.

Having grown up within the ancient kingdom of Mercia, still referenced today in such titles as the West Mercia Police, I feel I’ve always been aware of the heritage of the Midlands of England. But that doesn’t mean everyone else is.

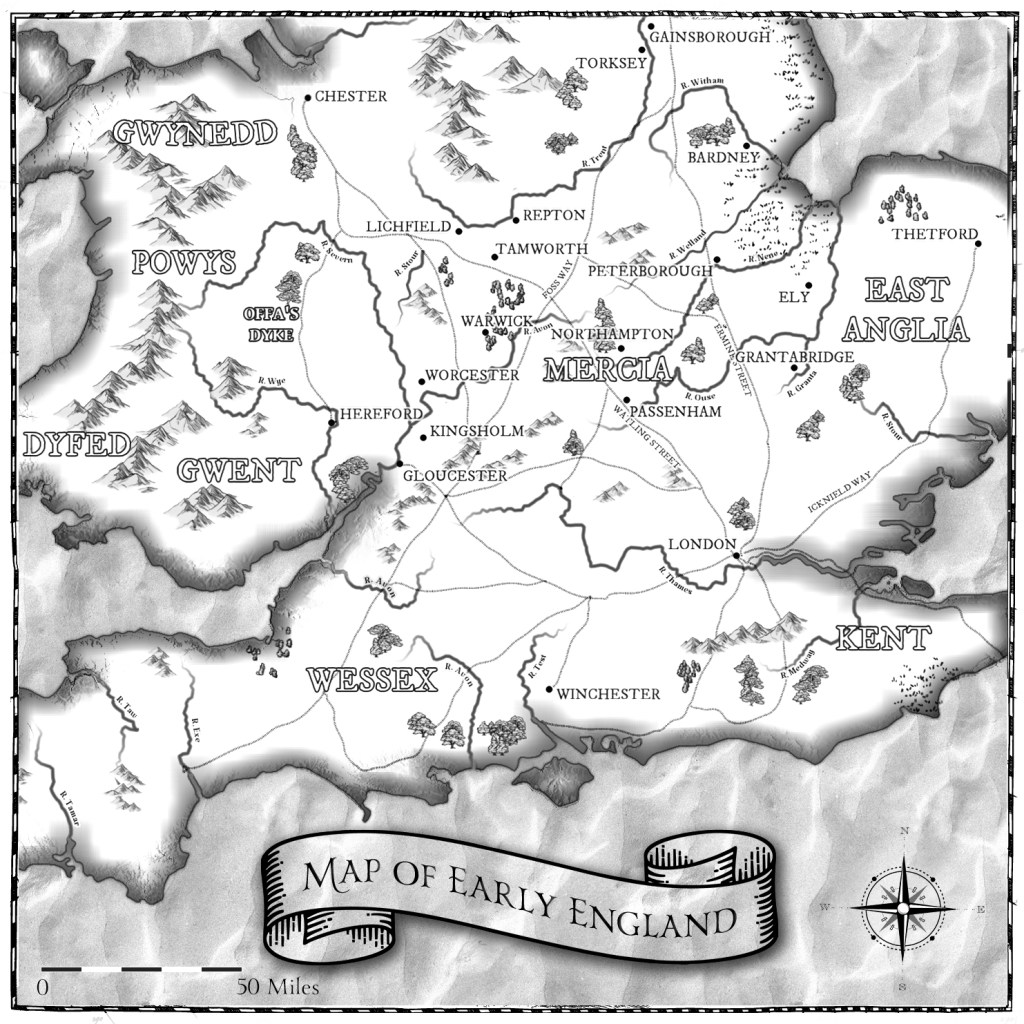

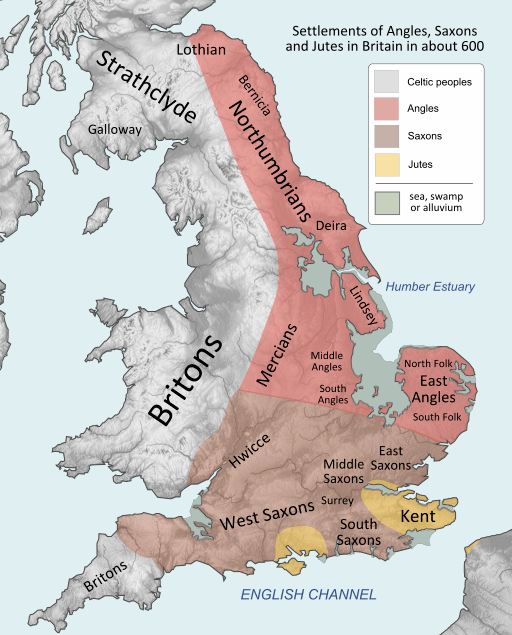

Where was Mercia?

Simply put, the kingdom of Mercia, in existence from c.550 to about c.925 (and then continuing as an ealdordom, and then earldom) covered the area in the English Midlands, perhaps most easily described as the area north of the River Thames, and south of the Humber Estuary – indeed, nerdy historians, and Bede, call the area the kingdom of the Southumbrians, in contrast to the kingdom of the Northumbrians – do you see what Bede did there?

While it was not always that contained, and while it was not always that large, Mercia was essentially a land-locked state (if you ignore all the rivers that gave easy access to the sea), in the heartland of what we now know as England.

What was Mercia?

Mercia was one of the Heptarchy—the seven ancient kingdoms that came to dominate Saxon England – Mercia, Wessex (West Saxons), the East Angles, Essex (East Saxons), Sussex (South Saxons) and Kent.

In time, it would be one of only four to survive the infighting and amalgamation of the smaller kingdoms, alongside Northumbria, the kingdom of the East Angles, Mercia, and Wessex (the West Saxons).

The End of Mercia?

Subsequently, it has traditionally been said to have been subsumed by the kingdom of Wessex, which then grew to become all of ‘England’ as we know it.

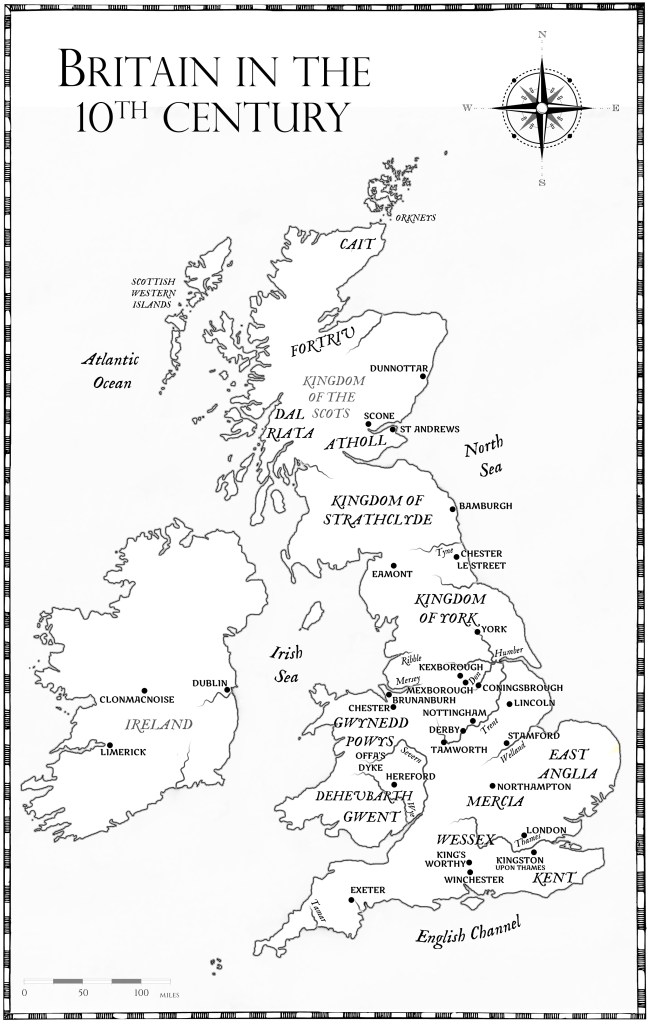

This argument is subject to some current debate, especially as the king credited with doing this, Athelstan, the first and only of his name, might well have been born into the West Saxon dynasty but was potentially raised in Mercia, by his aunt, Lady Æthelflæd, and was, indeed, declared king of Mercia on the death of his father, King Edward the Elder in July 924, and only subsequently became king of Wessex, and eventually, king of all England.

Mercia’s kings

But, before all that, Mercia had its own kings. One of the earliest, and perhaps most well-known, was Penda, in the mid-7th century, the alleged last great pagan king. (Penda features in my Gods and Kings trilogy). Throughout the eighth century, Mercia had two more powerful kings, Æthelbald and Offa (of Offa’s Dyke fame), and then the ninth century saw kings Wiglaf and Coelwulf II (both of whom feature as characters in my later series, The Eagle of Mercia Chronicles and the Mercian Ninth Century), before the events of the last 800s saw Æthelflæd, one of the most famous rulers, leading the kingdom against the Viking raiders.

The Earldom of Mercia

And even when the kingdom itself ceased to exist, it persisted in the ealdordom and earldom of Mercia, (sometimes subdivided further), and I’ve also written about the House of Leofwine, who were ealdormen and then earls of Mercia throughout the final century of Saxon England, a steadfast family not outmatched by any other family, even the ruling line of the House of Wessex.

In fact, Mercia, as I said above, persists as an idea today even though it’s been many years since the end of Saxon England. And indeed, my two Erdington Mysteries, are also set in a place that would have been part of Mercia a thousand years before:) (I may be a little bit obsessed with the place).

Posts

It’s International Women’s Day 2024. Here’s to the women of the tenth century in Saxon England.

I’ve made it somewhat of a passion to study the royal women of the tenth century. What drew me to them was a realisation that while much focus has rested on the eleventh century women, most notably Queen Emma and Queen Edith, their position rests very much on growing developments throughout the tenth century. It also helps that there is a surprising concurrence of women in the tenth century, the early years of Queen Elfrida, England’s first acknowledged crowned queen, find the ‘old guard’ from previous reigns, mixing with the ‘new guard’ – a delightful mix – it must be thought – of those experienced women trying to teach the younger, less experienced women, how to make their way at the royal court, perhaps with some unease from all involved.

Lady Elfrida, or Ælfthryth (I find it easier to name her as Elfrida) was the first of these women to catch my eye. Her story, which can be interpreted as a love story if you consult the ‘right’ sources, fascinated me. The wife of a king, mother of another king, and in time, grandmother, posthumously, to two more. But, it was her possible interactions with her husband’s paternal grandmother, the aging but long-lived Lady Eadgifu, and maternal grandmother, Lady Wynflæd, as well as probable unease with her second husband’s cast-off second wife, that really sparked my imagination. I could well imagine the conversations they might share, and the dismay they might feel around one another. Lady Elfrida replaced a wife who was not crowned as queen, and also replaced a grandmother who had never been crowned as queen but had long held a position of influence for over forty years at the Wessex court.

Equally, Elfrida’s husband had been surrounded by women from his earliest days. His mother had died, perhaps birthing him, but he had two grandmothers, a step-mother, a foster-mother and his (slightly) older brother’s wife, who would have been instrumental in his life, not to mention his first two wives. As such, it was the personal interactions of the women that called to me, and the tragedy and triumphs of their lives, and, I confess, an image of Dame Maggie Smith holding sway in Downton Abbey that drew me to the women of this period.

I’ve gone on to write fictionalised accounts of many of these women, and then, frustrated by the lack of a cohesive non-fiction account, I’ve also written a non-fiction guide detailing the scant information available for these women.

https://books2read.com/TheRoyalWomenWhoMadeEngland

You can read more about the royal women on the blog.

The daughters of Edward the Elder

The religious daughters of Edward the Elder

Did England’s first crowned queen murder her stepson?

Posts

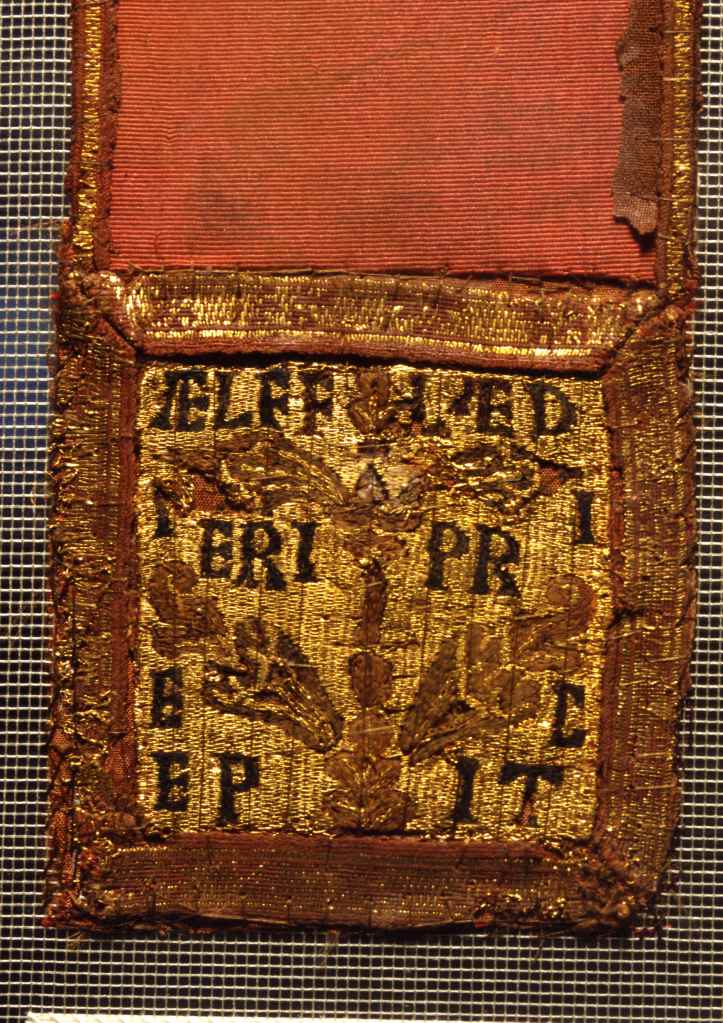

The Ælfflæd ‘stole’ from St Cuthbert’s tomb – The Royal Women Who Made England

When I was writing The Royal Women Who Made England, I discovered that there is potentially one surviving item that could be associated with these royal women. While the identification is not certain, it seems highly likely that some religious items, discovered in the tomb of St Cuthbert in Durham, when it was opened in 1827, could have either been stitched by Ælfflæd herself, or commissioned at her request. The item has the following words stitched on it Ælfflæd Fiere Precepit (Ælfflæd had [this] made) – translation from E Coatsworth The Embroideries from the Tomb of St Cuthbert.

Ælfflæd was the second wife of Edward the Elder (899-924). It’s believed they probably married AFTER he became king of Wessex on the death of his father in 899. She was the mother to at least six daughters, and two sons, one of whom became king after his father’s death, for a brief 16 days. Her stepson, Athelstan, then became king of Wessex. Two of her daughters married into the ruling families of East and West Frankia. Another two daughters married into influential families in Europe. Two others spent their adult lives in a nunnery, one as a lay sister, and one as a nun.

The embroideries consist of a stole, a maniple and a possible girdle, and are believed to have been made for Bishop Frithestan – indeed, the other end of the embroidery reads Pio Episcopo Fri∂estano (for the pious bishop Frithestan). So, together it reads Ælfflæd had this made for the pious bishop Frithestan. Frithestan was the bishop of Winchester in the early tenth century. It’s likely he never received them, for why else would they have found their way to Durham and the tomb of St Cuthberht?

There are two possible reasons for this. Firstly, Ælfflæd may have either died, or no longer been married to the king when they were completed. Edward the Elder remarried Eadgifu, his third wife sometime between 917-919. We don’t know if this was because his second wife had died, or merely because he wished to take a new wife. Secondly, Bishop Frithestan fell out with the House of Wessex at about this time. Indeed, he played no part in King Athelstan’s coronation. The expensive commissions, with gold thread, therefore never came into the hands of Bishop Frithestan. Where they might have been for the intervening period, would be interesting to know.

When King Athelstan (924-939) made his famous trip to Chester Le Street in c.934, it’s written that he gifted the community of St Cuthbert with a stole, a maniple and a girdle. It’s believed that it’s these items, made by, or commissioned by his stepmother, that he gave. (The religious house from Chester Le Street moved to Durham in 1104). St Cuthbert was a north-east saint, who lived on Lindisfarne/Holy Island in the 600s, and while it’s believed the religious house fled from Lindisfarne in the wake of the Viking raider invasions and were essentially ‘on the move’ for over a hundred years, this interpretation is now being questioned by Dr David Petts and the excavations taking place on Lindisfarne. Whatever happened to the community in that period, they were extremely influential in the north of England, and did eventually settle at Chester Le Street.

The survival of these items is astounding. There are only, according to E Coatsworth, three such ‘large’ items from the Saxon era, the Bayeaux tapestry, the Durham embroideries and those of St Catherine in Maaseik, Belgium. If these items were truly made by Ælfflæd, then they are unique. I can think of no other item that survives from the era and which the royal women may themselves have touched. When I saw this image, I was astonished by the vibrancy of the gold thread. I imagine I’m not alone in that.

You can read The Royal Women Who Made England: The Tenth Century in Saxon England now if you’re in the UK, or from March if you’re in the US. It can also be purchased in epub version direct from Pen and Sword.

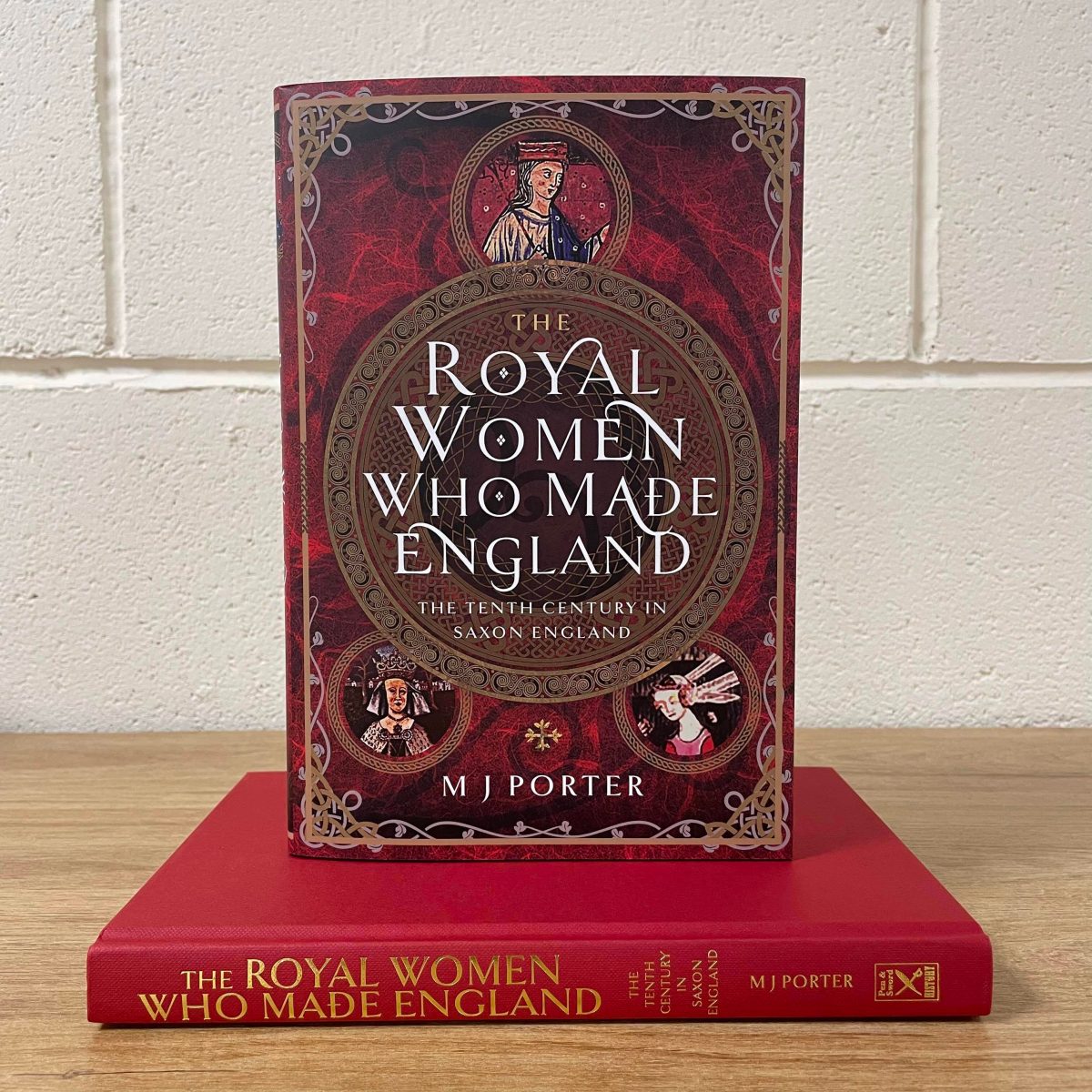

My first gold-lettered spine:) The Royal Women Who Made England

Here she is, and what a thing of beauty.

And the epub version is now saying it’s available direct from Pen and Sword using this link if you don’t want to wait for a hardback to be delivered.

https://www.pen-and-sword.co.uk/The-Royal-Women-Who-Made-England-ePub/p/50369

Reviews are starting to come in, and I’d like to thank all the reviewers for taking the time to have a look at The Royal Women Who Made England. You can check out the reviews over on the Pen and Sword website.

In the meantime, don’t forget to enter the combined competition between my two publishers for signed copies of The Royal Women and King of Kings (UK only. Closing date 6th Feb 2024). You can find the details here.

And, I have another little video to share with you below about one of the later Anglo-Norman sources I made use of while researching the book.