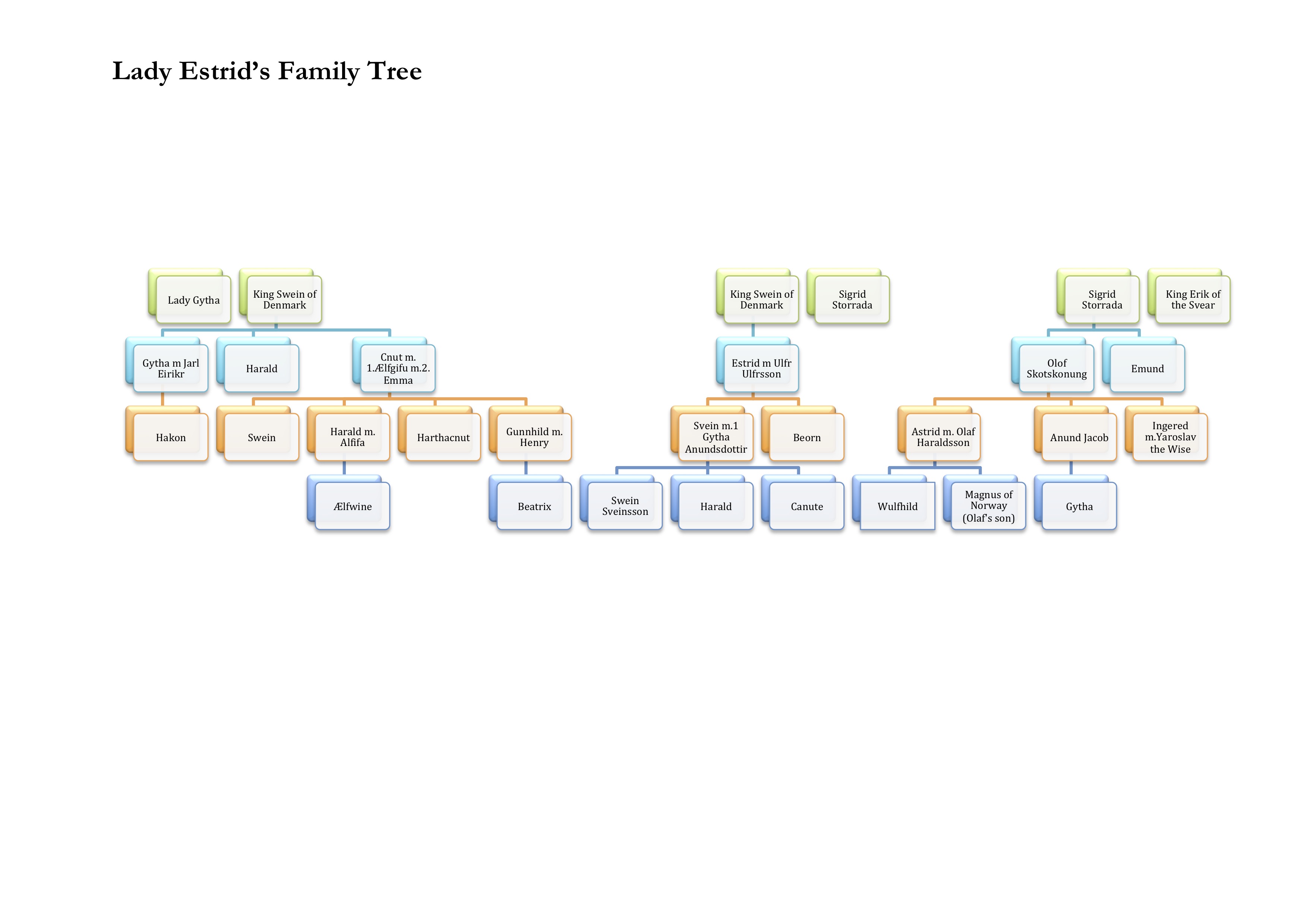

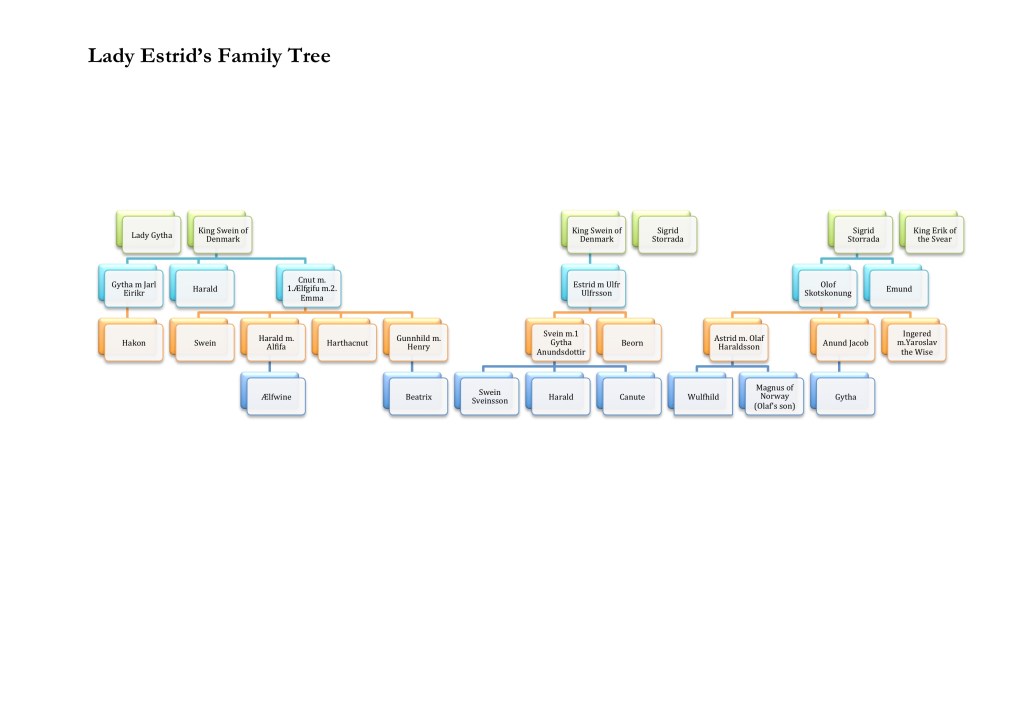

Lady Estrid was born into a large and illustrious family with far-reaching influence over Denmark, Sweden, Norway and England.

I’ve put together some genealogical tables of the main families to make easier to work out how everyone connected. (You can click on the images to make them bigger).

Due to a lack of information, I have made little mention of the rest of Estrid’s half-sisters, of which she had three or four. I feel it perhaps also helped the story a little – it was complicated enough as it was without giving them the capacity to meddle in affairs in Denmark.

To break it down into more palatable chunks, Lady Estrid’s mother was married twice, once to King Swein of Denmark (second) and also to King Erik of the Svear (first). King Swein was also married twice (in my story at least – as it is debated), to Lady Gytha (who I take to be his first wife) and then to Lady Sigrid (who I take to be his second wife.) Swein was king of Denmark, Erik, king of the Svear (which would become Sweden), and so Sigrid was twice a queen, and she would have expected her children to rule as well, and her grandchildren after her. Sigrid was truly the matriarch of a vast dynasty.

She would have grandchildren who lived their lives in the kingdom of the Rus, in Norway, in England, and Denmark.

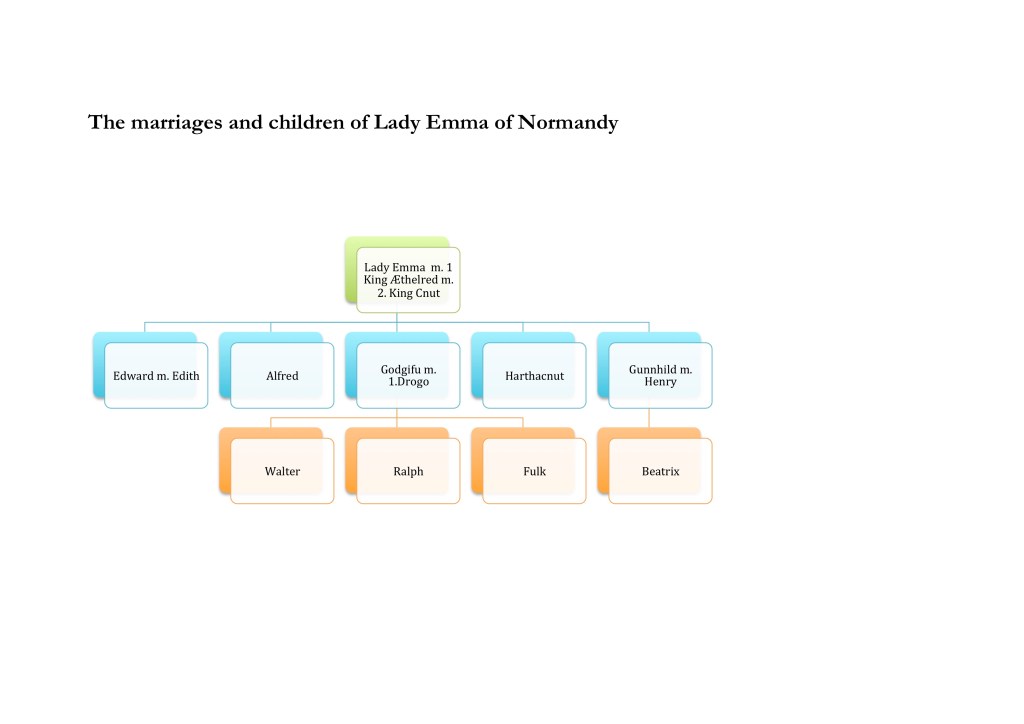

And Sigrid wasn’t the only ‘double queen.’ Lady Emma, twice queen of England, was first married to King Æthelred and then to King Cnut, Estrid’s brother.

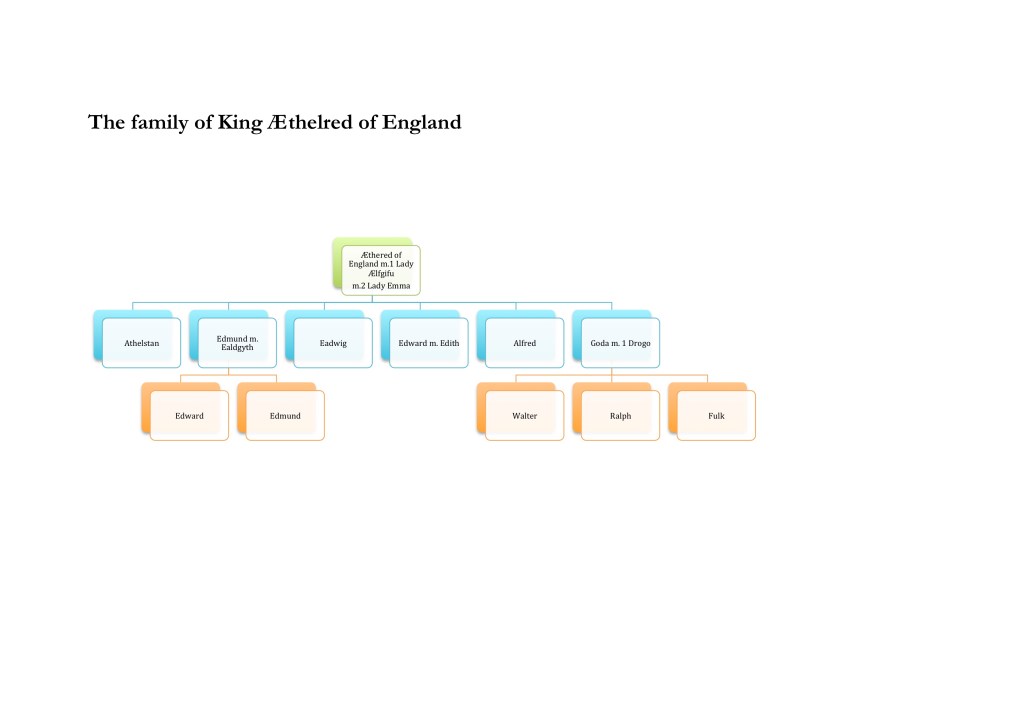

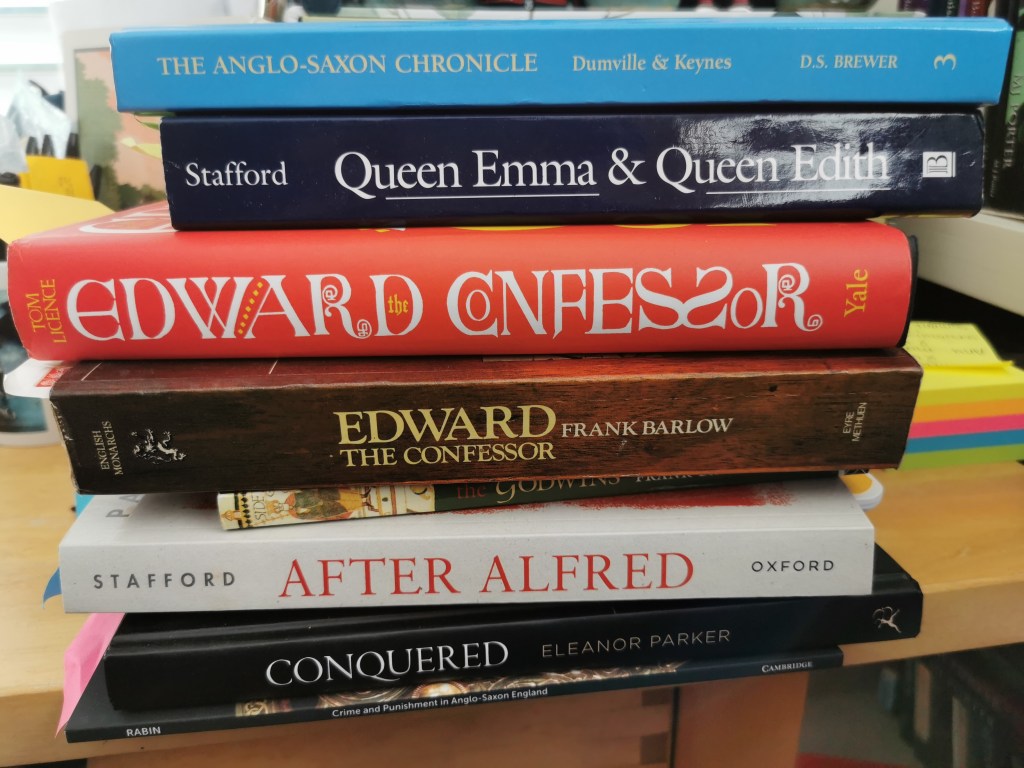

Not that it’s possible to speak of Lady Emma’s children from her two marriages, without considering the children of her first husband’s first marriage. King Æthelred had many children with his first wife, perhaps as many as nine (again, a matter for debate), the below only shows the children mentioned in Lady Estrid. Readers of The Earls of Mercia series, and the Lady Elfrida books, will have encountered the many daughters, as well as sons.

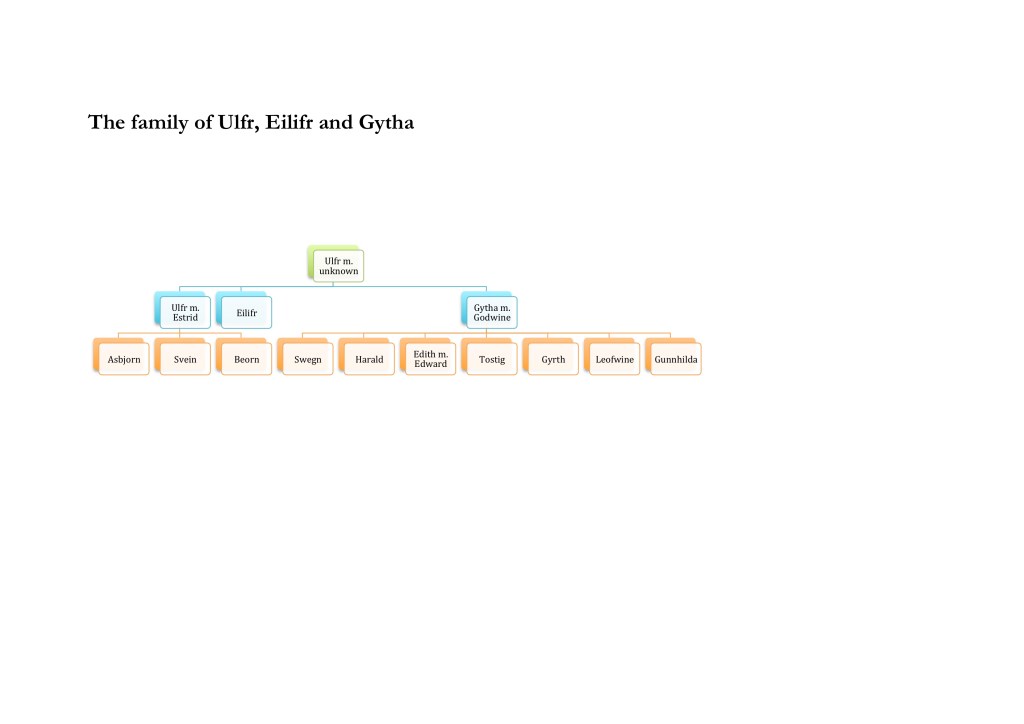

One of the other family’s that had the most impact on Lady Estrid, was that of her third husband, and father of her two sons, Jarl Ulfr.

Ulfr had a brother and a sister, and while little is known about the brother, it is his sister who birthed an extremely illustrious family, through her marriage to Earl Godwine of Wessex. (The family tree doesn’t include all of her children.)

Four such powerful families, all intermarried, make for a heady mix.

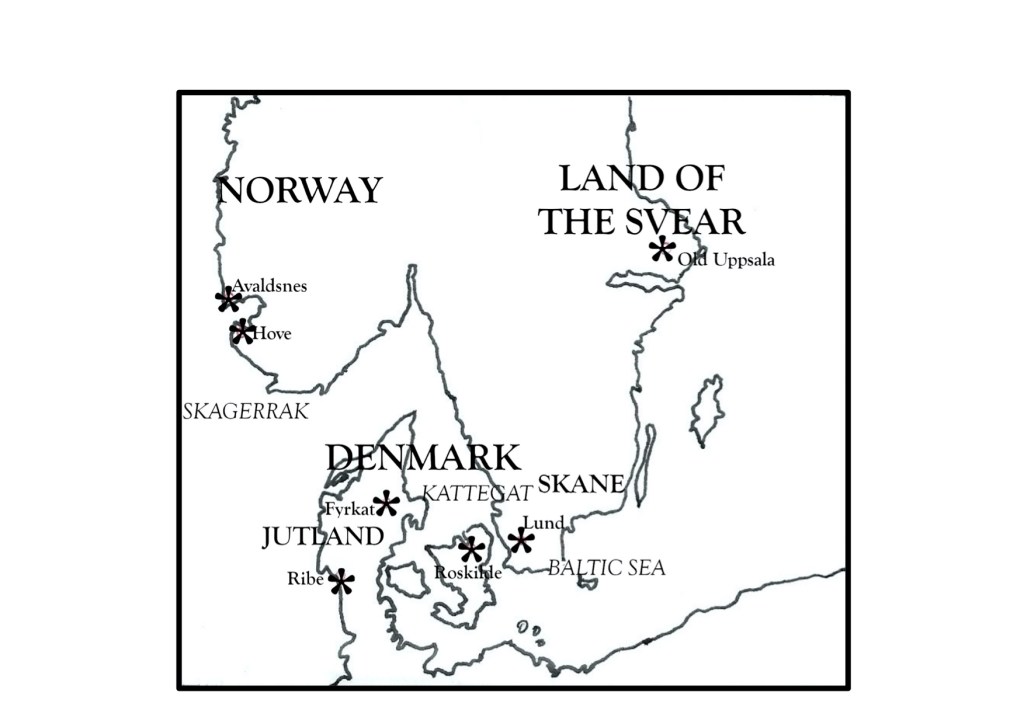

For the modern reader, not only are the family dynamics complicated to understand, but so too is the geography. Sweden was not Sweden as it is today, and the reason I’ve insisted on calling it the Land of the Svear. But equally, Denmark was larger than it’s current geographical extent, covering Skåne, (in modern day Sweden) as well. The map below attempts to make it a little clearer. Norway is perhaps the most recognisable to a modern reader, but even there, there are important difference. King Swein claimed rulership over parts of Norway during his rule, and so too did King Cnut. But, Denmark isn’t the only aggressor, there were rulers in all three kingdoms who wished to increase the land they could control, King Cnut of Denmark, England, Skåne and part of Norway, is merely the most well-known (to an English-speaking historian.)

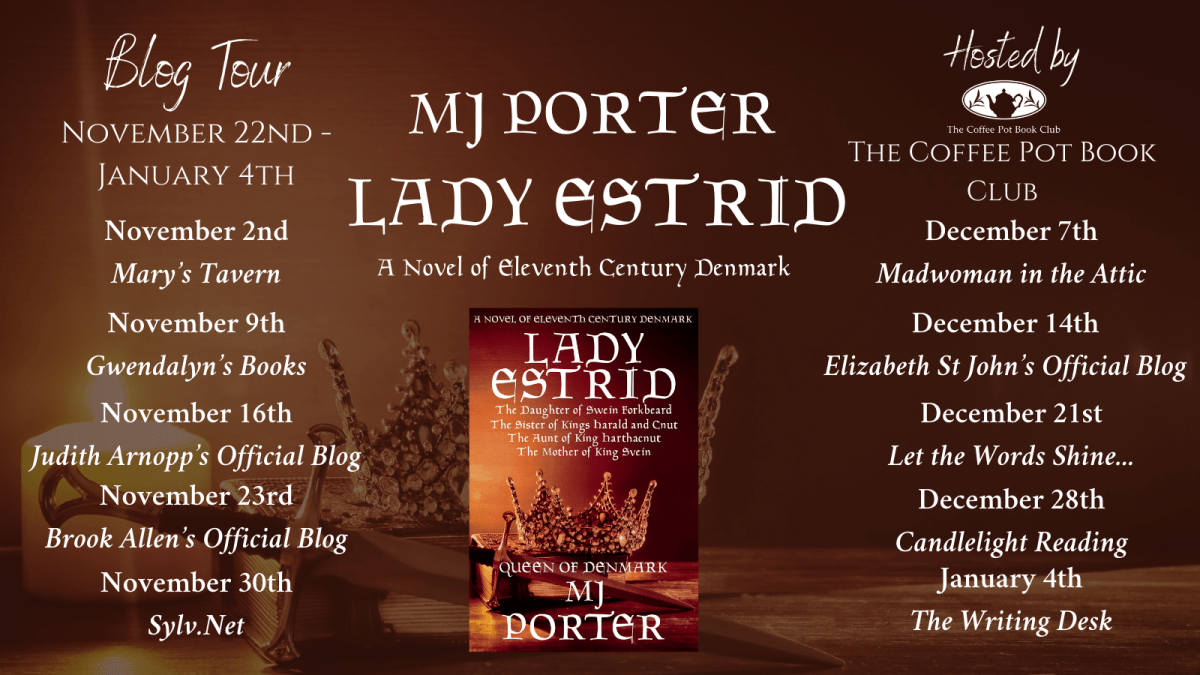

Lady Estrid is available now

Lady Estrid is a standalone novel, but it does incorporate characters and events from The Earls of Mercia series. So, if you’ve not yet read The King’s Brother, it might contain some spoilers, and vice versa.

I have also written about Lady Estrid’s brother, Cnut, and her father, Swein. I classify the books as side stories to the main Earls of Mercia series, but they can all be read as standalones, or as a trilogy about the powerful family.

Interested in the unknown women of the tenth and the eleventh century? I’ve written about quite a few of them now. Check out The Tenth Century Series, featuring Lady Ælfwynn, Lady Eadgifu and the daughters of Edward the Elder, and the stories of Lady Elfrida as well as The Royal Women Who Made England.