I can never miss an opportunity to ask a fellow Saxon author questions about why they write about the same period as me. My thanks to Mercedes for answering them.

What drew you to the character of Godwine and his wife and children?

While I was writing my first book, Heir To A Prophecy, I introduced my protagonist Walter into London on the day Godwine came back from exile. It was a plot device to introduce him to Harold Godwineson (Walter took out one of the Normans fleeing through the crowd). I didn’t know who Godwine was, but I couldn’t shake him loose! I went back fifty years and discovered a great story.

Naturally, very little is known about these historical characters, and I had two challenges that dovetailed nicely. Both had to do with not wanting to fall into that old predictable trap concerning characters. First of all, the love interest. There are so many love stories that seem formulaic. I didn’t want that same old theme: disliking each other first, then falling in love (and all the variations thereof). On the other hand, I understand that there needs to be some kind of stress in the romance to make a good story. It was obvious that Godwine had a happy marriage (or at least a productive one) since they had so many children. I was really intrigued by the discrepancy of their social status. Godwine was a commoner, and Gytha was a noble (or the Danish equivalent). At the same time, I had a hard time figuring out why Swegn, the firstborn, turned into such a bad egg. I don’t believe a character should be all good or all bad. People just aren’t like that. Even wicked characters act that way for a reason; sometimes they have good qualities that get buried under their more powerful bad qualities. Finally I had an inspiration: if Godwine’s marriage started out in anger, or stress (Gytha was given to him in marriage, but she didn’t have to go willingly), perhaps the firstborn would be neglected and unloved. That would explain his subsequent behaviour. It took some doing to make that work, but I’m happy with the result.

What part of your research did you enjoy the most?

I love research; I actually prefer the research to the writing. I knew I was going to like Godwine. What surprised me was how fascinated I was with Canute. He was an incredibly complicated character. From the angry king-to-be that cut the noses off his 200 hostages after England rejected him in favour of Aethelred the Unready, he eventually became a very successful monarch. Most of all, I loved the single combat between him and Edmund Ironside, where he cleverly talked himself out of getting flattened by convincing Edmund to split the kingdom between them. This may well be apocryphal, but that’s the challenge of writing about events 1000 years ago. We have more legends than “history” to work with, and the legends are so good they stick.

Was there a resource that was invaluable?

I hate to admit this because it makes me sound so old, but when I was writing Godwine Kingmaker there was no internet. Back then, I was living in St. Louis, MO—a very nice town but far from the libraries I needed. If the book wasn’t in the card catalogue, it might as well not even exist. So, like any warm-blooded researcher who didn’t have a family to take care of, I pulled up stakes and moved to New York. The day I discovered the New York Public Library my life changed forever. I found authors I never knew about, and finally got my hands on my first copy of Edward A. Freeman’s “History of the Norman Conquest of England”. I thought I had gone to heaven! In six volumes he wrote about every aspect of Anglo-Saxon England I could possibly think of. (These days Freeman is somewhat out of fashion, but he’s still my go-to when I need to look something up; he has never failed me yet.) Copy machines were available for ten cents a page, but as much as I needed to copy, I’d be better off buying the books—if I could find them. No such luck until a couple of years later, when I went on a book-buying trip to England and discovered Hay-on-Wye. A breakthrough! Those were the days (the late ’80s) when old used hardbacks were still easy to find, and I discovered my very own set of Freeman which I gleefully brought home. That was the original basis of all my research. Those books are still my most precious possession, though now you can find them online (scanned, of course).

Did you learn anything that surprised you while writing the trilogy?

Back to Canute again. While delving into Harold’s relationship with Edith Swan-neck in THE SONS OF GODWINE, again I wanted to avoid the usual romantic formulas. First of all, I had to decide whether Edith was a luscious young thing or an attractive widow; both possibilities were referred to in the histories. By lucky chance, I stumbled across Canute’s Law Code of 1020, designed to smooth relations between the Danes and the Saxons. One section dealt with heriot (essentially an inheritance tax), not a new concept. But I found a reference to protecting widows. Canute gave a widow twelve months to pay her husband’s heriot. But she had to remain unmarried or she would lose both her morning-gift and all possessions from her former husband. If some unscrupulous man coveted her inheritance and forced her to marry him, all the possessions would pass on to the nearest kinsman. The king would lose the heriot tax if this were to happen, so it was also written into Canute’s law that a widow should never be forced to marry a man she dislikes. After all, the Crown had much to lose. So I decided to make Edith a recent widow trying to evade the attentions of an unwelcome suitor, while she and Harold conducted their relationship.

What is your personal opinion? Do you believe that William the Conqueror was justified in claiming England? Do you believe he had been promised it?

Apparently the whole justification came down to King Edward the Confessor’s promise to William when the duke visited England during Godwine’s exile. I think we can negate the assertion that Edward felt some sort of gratitude for having been sheltered there during his exile. When Edward left Normandy in 1041, William was only 13 years old and Edward was 38. With that age gap, it seems unlikely that the two of them would have developed a close relationship, so any alleged gratitude Edward might have owed probably belonged to William’s father Robert, dead by 1035.

Now, during Godwine’s exile in 1051, it’s far from certain that William even visited England. Some historians thought he would have been too busy putting down rebellions to leave his country even for a short time. If William did visit England and if Edward offered him the crown at this point, it’s curious why he would have done so. The king knew that it was up to the Witan to decide the succession. However, considering his antagonism toward the Godwines (he even put the queen in a nunnery while Godwine was in exile), perhaps he made this alleged promise out of spite.

However, it’s my belief that the blame can be placed upon Robert of Jumièges, former Archbishop of Canterbury and arch-enemy of Earl Godwine. Robert is one of the Normans who fled from London once it was clear that Godwine was back in control. He’s almost certainly the one who kidnapped the hostages, Godwine’s son Wulfnoth and grandson Hakon, and brought them to Normandy. In my interpretation, Jumièges acted on his own when he told William that Edward declared him heir to the English throne, and here are the hostages to guarantee his promise. What a great revenge on Godwine and all of England for kicking him out! Why wouldn’t William believe such an opportune offer?

Who is your personal favourite member of the House of Godwine?

When all is said and done, Earl Godwine still holds his place as my favourite. If it weren’t for him, there would be no Harold Godwineson Last Anglo-Saxon King. I think he helped smooth the relations between the conquering Danish king and his unhappy countrymen, then moved on to staunchly defend the Saxons against the hated Normans. His rise to power was unprecedented, and I think his fall was tragic, though not in the way we usually think of as a tragedy. Having sacrificed so much for the wrong son, he had nothing left to live for as he watched Harold take his place in the hearts of his people.

As you know, I write about the Earls of Mercia. What opinion did you form of the rivals to the House of Godwine while researching and writing your books?

I wondered if you’d ask that question! Of course, by the late Anglo-Saxon period, I think the Mercian earls had lost much of their lustre. Old Earl Leofric certainly held his own against Earl Godwine (with the help of Earl Siward of Northumbria). It seems the odds were against Leofric as Godwine’s sons were granted their own earldoms, shifting the balance of power in Godwine’s favour. At this stage, I always thought of them as bitter, unhappy competitors who could never regain their former glory. After King Edward died, Harold tried to join forces with the grandsons of Leofric, Edwin and Morcar, but I don’t think their association was ever successful. William the Conqueror certainly put an end to that.

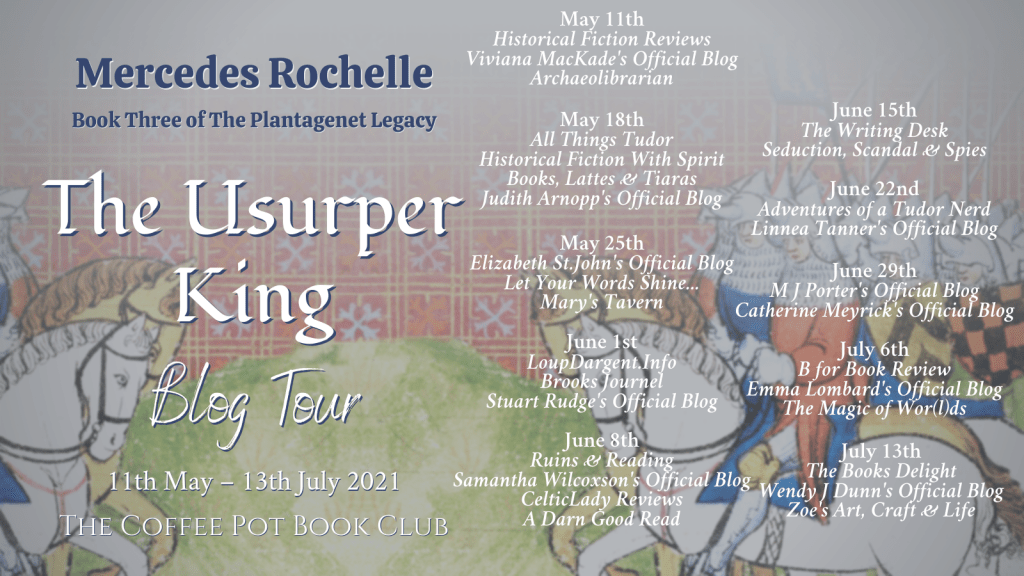

Thank you for answering my questions with such insight. I hope you enjoy the blog tour.

Here’s the blurb:

They showed so much promise. What happened to the Godwines? How did they lose their grip? Who was this Godwine anyway, first Earl of Wessex and known as the Kingmaker? Was he an unscrupulous schemer, using King and Witan to gain power? Or was he the greatest of all Saxon Earls, protector of the English against the hated Normans? The answer depends on who you ask.

He was befriended by the Danes, raised up by Canute the Great, given an Earldom and a wife from the highest Danish ranks. He sired nine children, among them four Earls, a Queen and a future King. Along with his power came a struggle to keep his enemies at bay, and Godwine’s best efforts were brought down by the misdeeds of his eldest son Swegn.

Although he became father-in-law to a reluctant Edward the Confessor, his fortunes dwindled as the Normans gained prominence at court. Driven into exile, Godwine regathered his forces and came back even stronger, only to discover that his second son Harold was destined to surpass him in renown and glory.

Buy Links:

This series is available on Kindle Unlimited

Amazon UK: Amazon US: Amazon CA: Amazon AU:

Meet Mercedes

Mercedes Rochelle is an ardent lover of medieval history, and has channeled this interest into fiction writing. She believes that good Historical Fiction, or Faction as it’s coming to be known, is an excellent way to introduce the subject to curious readers. She also writes a blog: HistoricalBritainBlog.com to explore the history behind the story.

Born in St. Louis, MO, she received by BA in Literature at the Univ. of Missouri St.Louis in 1979 then moved to New York in 1982 while in her mid-20s to “see the world”. The search hasn’t ended!

Today she lives in Sergeantsville, NJ with her husband in a log home they had built themselves.

Connect with Mercedes

Book Bub: Amazon Author Page: Goodreads: