And here are some of my favourite moments in the novel, as Icel marvels at what’s been left behind by those who came before him.

And then we come to a stop. In front of me, there’s a structure I can hardly comprehend. All around it are smaller piles of stones, no doubt the remains of other buildings. Beneath my feet, I walk on gravel and tufted grasses. Lifting my feet to peer down, I question whether the whole place was once laid with stone upon which to walk? I pause, gaze around me. In the distance, almost further than the entire settlement of Tamworth, are hints of more walls, more random pieces of white stone, discarded and abandoned. I don’t see any crops or greenery, only shrivelled weeds and little else. If I were to live here, where would I grow my food? Where would Wynflæd harvest her herbs from? The place is dusty and barren, just as Wulfheard told me.

There’s a forest of stone plinths guiding us towards the smell of campfires, with some immobile figures on them, all missing arms, or legs, or feet or even heads, their whiteness attesting to being made from some sort of priceless stone. To me, they look so similar to the bodies of the dead that, for a moment, I can’t quite decipher the intent behind them. And Brihtwold is no help. I can hardly ask what this place is because I should already know.

‘They’re in the centre of the settlement, in a stone-built building, one of the few that still stands to two levels. We head towards the east, and it’s in the centre. It’s difficult to miss it during the daytime, what with the ruined columns that still stand, and the statues that guide our steps towards it, but in the darkness of night, it might be a little more tricky.’

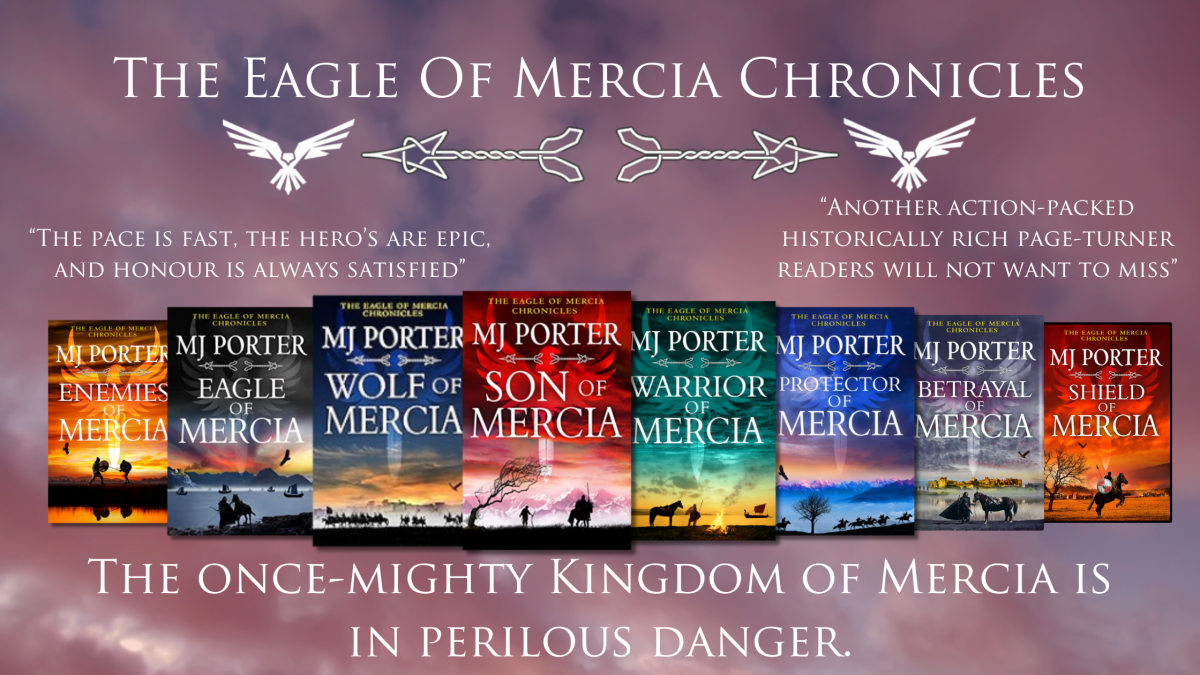

Wolf of Mercia is book 2 in The Eagle of Mercia Chronicles, and I had a lot of fun thinking about what the settlement might have looked like in the 830s, hundreds of years after Londinium was abandoned.

You can read all about Londonia below.

Londonia, the setting for Wolf Of Mercia

I’ve been avoiding taking my Saxon characters to London for quite some time. Bernard Cornwell, I feel, has done a fine job of explaining London to readers of his The Last Kingdom books. I wasn’t sure I had a great deal more to offer. But how wrong I was.

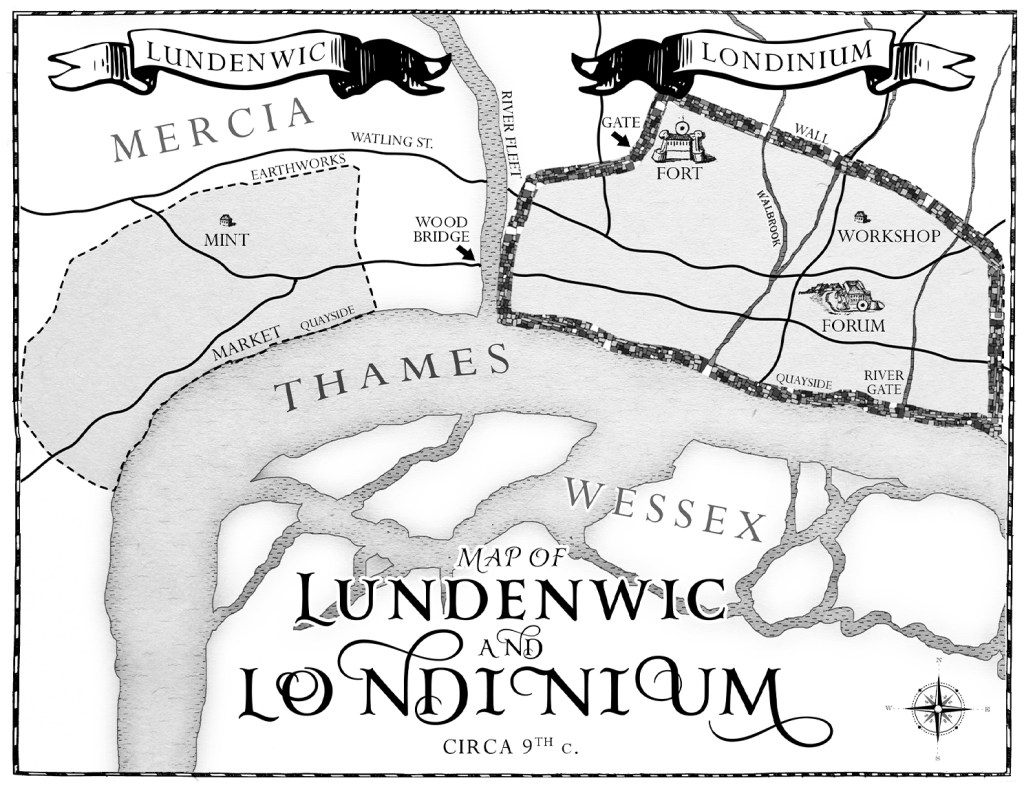

Londonia, the name suggested by Rory Naismith in his Citadel of the Saxons, for the combined settlement of the seventh century, seems a neat and tidy way of referencing both settlements, the Roman Londinium, and the Saxon Lundenwic. And yet, both settlements were so very different, it seems wrong to try and make them appear unified, at a time when they really weren’t. The ‘wic’ element of the name means it refers to a market site, somewhere where trade took place.

The River Fleet, now a lost river of London, once divided these two settlements, the one built of stone with high walls that may have been as tall as six metres, and the other, built of wattle and daub, and entirely open to the River Thames. It’s believed the lost River Fleet might have been substantial enough over 1200 years ago that a bridge was built over it. And this reminds travellers to the past of the mistake of assuming landscapes haven’t altered. It’s often easy to remember that buildings and roads might have changed, even that rivers might have changed course, and that sea levels might have risen or fallen, but an entirely lost river is a new one for me.

Neither should we consider Londinium, the Roman fort, to always have appeared as we imagine it. A brief look through the archaeological details for Roman Londinium, reveal that it changed dramatically over time. Most obviously, the walls for which it’s so famous, were not part of the original structure, they weren’t built until AD180-220. The earliest timbers so far found on the site date to nearly one hundred and fifty years earlier.

The number of inhabitants inside those stone walls seems to have waxed and waned throughout the period of Roman Britain, and there is some suggestion that it might have been abandoned as early as the fourth century, and therefore, much before the acknowledged ‘end of Roman Britain’ came in the early years of the fifth century. The bridge crossing from Londinium to Southwark, on the southern shore, may also have disappeared by the fourth century. There is therefore, a great deal to unpick. And for my characters, in the ninth century, just what would they have walked through? It’s an intriguing question. Would there have been abandoned statues, half-collapsed buildings, an eerie quiet, or would much of that have already disappeared, perhaps even been ‘robbed out’ as we know happened in other places, most notably along Hadrian’s Wall where stone often appears in the fabric of later churches.

As to Lundenwic? Are we to truly believe that it was little more than a boggy riverfront site? In fact, the location was chosen precisely to miss the boggy area from where the River Fleet would have joined the River Thames. But why move from behind those stone walls? The huge area of Londinium, was simply too vast for a much diminished population to attempt to control. The settlement that developed in Lundenwic was half as big as that of the Roman site, with a population of around 7000 (compared to an estimated 25,000-30,000 in Londinium at its peak). It consisted of small buildings, tightly packed together with small alleyways leading off from a few main roads. But, these main roads were fitted with wooden drainage ditches. While it might not have been the majestic sweep of a huge walled city, it wasn’t quite the hovel it’s often been betrayed as.

And, these two separate settlements, didn’t last for that long individually. But, in the year AD830, it’s just possible that young Icel may have walked through a serviceable, if abandoned Roman settlement when he visited Londinium, and that was too good an opportunity not to incorporate into the new book, Wolf of Mercia.