Today, I’m welcoming Jane Davis to the blog with a fascinating post about her new book, Small Eden.

In England’s Green and Pleasant Land

In Victorian England, Carshalton and nearby Mitcham were known for their physic gardens, where plants were grown for medicinal and cosmetic use. Peppermint, lavender, camomile, aniseed, rhubarb, and liquorice were stable crops but today the name Carshalton is best associated with lavender growing. Of the many lavender farms that used to exist, only two remain. Mayfield Lavender is the larger of the two. In the summer months, people come a long way to see it. https://www.mayfieldlavender.com/

At a time when few women ran their own businesses, I was delighted to stumble across the story of Sarah Sprules. Sarah had worked alongside her father in his physic garden and took over his business after he died. Her produce was known worldwide. Her lavender water won medals at exhibitions in Jamaica and Chicago, but the highest accolade she held was her Royal Warrant to supply lavender oil to Queen Victoria, bestowed on her after the Queen and Princess Louise visited her during August 1886. The royal connection proved especially beneficial as Queen Victoria had so many European relatives.

But that wasn’t all. it was the discovery that Mitcham was once the opium-growing capital of the UK that made me decide my leading man, Robert Cooke, should be a physic gardener. This chapter has been written out of the history books, but in the nineteenth century, far from having a seedy reputation, opium use was respectable. Queen Victoria’s household ordered opium from the royal apothecary, and Prime Minister William Gladstone is said to have drunk opium tea before important speeches. It was used an anaesthetic, in sedatives, for the relief of headaches, migraines, sciatica, as a cough suppressant, to treat pneumonia, and for the relief of abdominal complaints and women’s cramps.

Mrs Beeton’s famous Book of Household Management recommended that no household should be without a supply of powdered opium and laudanum, and she included a recipe for laudanum. But awareness of its dangers was beginning to spread.

Short Matching Excerpt from Small Eden

It was Freya who first showed him Dr Bull’s Hints to Mothers, a pamphlet highlighting the dangers of opiates in the nursery. Of course he doesn’t agree with the practice of dosing up babies so that they sleep all day, he told his wife, but yes, he’s aware it goes on. Working mothers have little choice but to leave children for hours at a time, so they doctor their gripe-water. And it’s not just the poor. Mothers read the labels that say Infant Preservative and Soothing Syrup. They think that ‘purely herbal’ and ‘natural ingredients’ means that products are safe. Though it was chilling to read about case after case of infant deaths linked to over-use.

As many as a third of infant deaths in industrial cities.

And he, who has buried two sons.

But even Dr Bull didn’t condemn the use of opiates outright. They are medicines, he wrote, and like any medicine, ought to be prepared by pharmacists. The trouble is, Robert told Freya, that until recently any Tom, Dick or Harry could operate a pharmacy. And hasn’t he been vocal in his support for an overhaul of the system?

***

Why did it take so long for opium to be banned?

In the 19th Century, Great Britain fought two wars to crush Chinese efforts to restrict its importation. Why? Because opium was vital to the British economy. And then there was the thorny issue of class. The upper and middle classes saw the heavy use of laudanum among the lower classes as ‘misuse’; however they saw their own use of opiates was seen as necessary, and certainly no more than a ‘habit’. Addiction wasn’t yet recognised. That would come later.

The anti-opium movement

In 1874, a group of Quaker businessmen formed The Society for the Suppression of the Opium Trade. Then in 1888 Benjamin Broomhall formed the Christian Union for the Severance of the British Empire with the Opium Traffic. Together, their efforts ensured that the British public were aware of the anti-opium campaign.

Short Matching Excerpt from Small Eden

“Indulge me if you will while I explain how the Indian trade operates – a system that the House of Commons condemned this April last. The East India Company – with whom I’m sure you are familiar – created the Opium Agency. Two thousand five hundred clerks working from one hundred offices administer the trade. The Agency offers farmers interest-free advances, in return for which they must deliver strict quotas. What’s so wrong with that? you may ask. What is wrong, my friends, is that the very same Agency sets the price farmers are paid for raw opium, and it isn’t enough to cover the cost of rent, manure and irrigation, let alone any labour the farmer needs to hire. And Indian producers don’t have the option of selling to higher bidders. Fail to deliver their allocated quota and they face the destruction of their crops, prosecution and imprisonment. What we have is two thousand five hundred quill-pushers forcing millions of peasants into growing a crop they would be better off without. And this, this, is the Indian Government’s second largest source of revenue. Only land tax brings in more.”

More muttering, louder. The shaking of heads and jowls.

“I propose a motion. That in the opinion of this meeting, traffic in opium is a bountiful source of degradation and a hindrance to the spread of the gospel.” Quakers are not the types to be whipped up into a frenzy of moral indignation, but their agreement is enthusiastic. “Furthermore, I contend that the Indian Government should cease to derive income from its production and sale.”

Robert looks about. Surely he can’t be the only one to wonder what is to replace the income the colonial government derives from opium? Ignoring this – and from a purely selfish perspective, provided discussion is limited to Indian production – his business will be unaffected. Seeing his neighbours raise their hands to vote, Robert lifts his own to half-mast. Beside him, Smithers does likewise.

***

The time comes when Robert Cooke must make a choice. He can either diversify, or he can gamble that the government will ban cheap foreign imports and that the price of domestic produce will rise. Robert Cooke is a risk-taker. He decides to specialise, and that decision will cost him dearly. It may even cost him his family.

Thank you so much for such a fascinating post. Good luck with your new book.

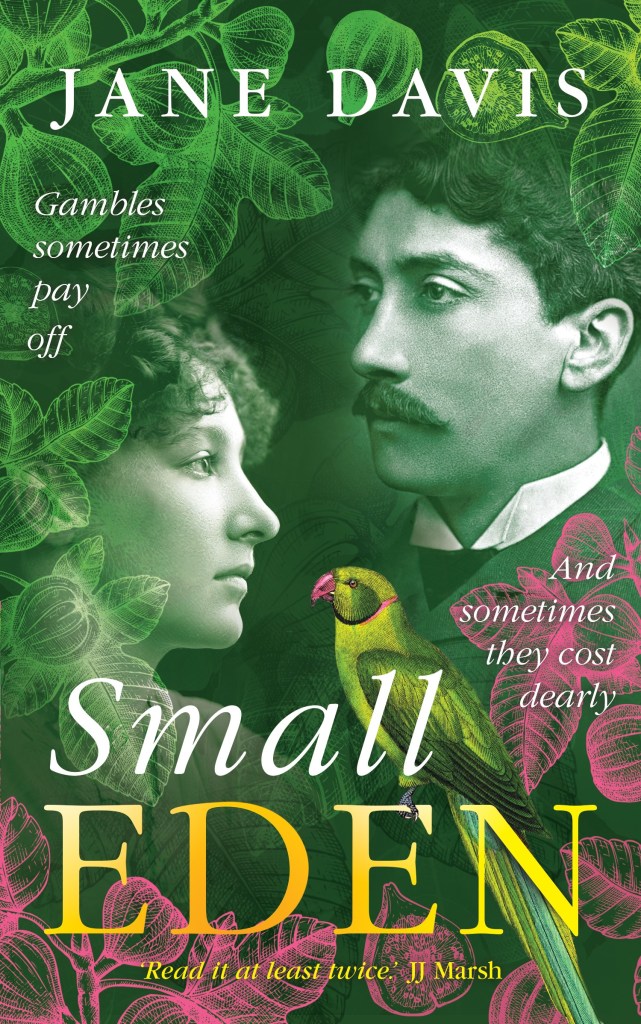

Here’s the blurb:

A boy with his head in the clouds. A man with a head full of dreams.

1884. The symptoms of scarlet fever are easily mistaken for teething, as Robert Cooke and his pregnant wife Freya discover at the cost of their two infant sons. Freya immediately isolates for the safety of their unborn child. Cut off from each other, there is no opportunity for husband and wife to teach each other the language of their loss. By the time they meet again, the subject is taboo. But unspoken grief is a dangerous enemy. It bides its time.

A decade later and now a successful businessman, Robert decides to create a pleasure garden in memory of his sons, in the very same place he found refuge as a boy – a disused chalk quarry in Surrey’s Carshalton. But instead of sharing his vision with his wife, he widens the gulf between them by keeping her in the dark. It is another woman who translates his dreams. An obscure yet talented artist called Florence Hoddy, who lives alone with her unmarried brother, painting only what she sees from her window…

Buy Links:

Amazon UK: Amazon US: Amazon CA: Amazon AU:

Barnes and Noble: Waterstones: (POD) / Trade paperback – Waterstones

Foyles: Kobo: iBooks: Smashwords:

Meet the author

Hailed by The Bookseller as ‘One to Watch’, Jane Davis writes thought-provoking literary page turners.

She spent her twenties and the first half of her thirties chasing promotions in the business world but, frustrated by the lack of a creative outlet, she turned to writing.

Her first novel, ‘Half-Truths and White Lies’, won a national award established with the aim of finding the next Joanne Harris. Further recognition followed in 2016 with ‘An Unknown Woman’ being named Self-Published Book of the Year by Writing Magazine/the David St John Thomas Charitable Trust, as well as being shortlisted in the IAN Awards, and in 2019 with ‘Smash all the Windows’ winning the inaugural Selfies Book Award. Her novel, ‘At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock’ was featured by The Lady Magazine as one of their favourite books set in the 1950s, selected as a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice, and shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2021.

Interested in how people behave under pressure, Jane introduces her characters when they are in highly volatile situations and then, in her words, she throws them to the lions. The themes she explores are diverse, ranging from pioneering female photographers, to relatives seeking justice for the victims of a fictional disaster.

Jane Davis lives in Carshalton, Surrey, in what was originally the ticket office for a Victorian pleasure gardens, known locally as ‘the gingerbread house’. Her house frequently features in her fiction. In fact, she burnt it to the ground in the opening chapter of ‘An Unknown Woman’. In her latest release, Small Eden, she asks the question why one man would choose to open a pleasure gardens at a time when so many others were facing bankruptcy?

When she isn’t writing, you may spot Jane disappearing up the side of a mountain with a camera in hand.

Connect with Jane:

Website: Twitter: Facebook: LinkedIn:

Pinterest: Book Bub: Amazon Author Page: Goodreads: