Here’s the blurb

Deceit and ambition threaten to undo the most fragile alliance.

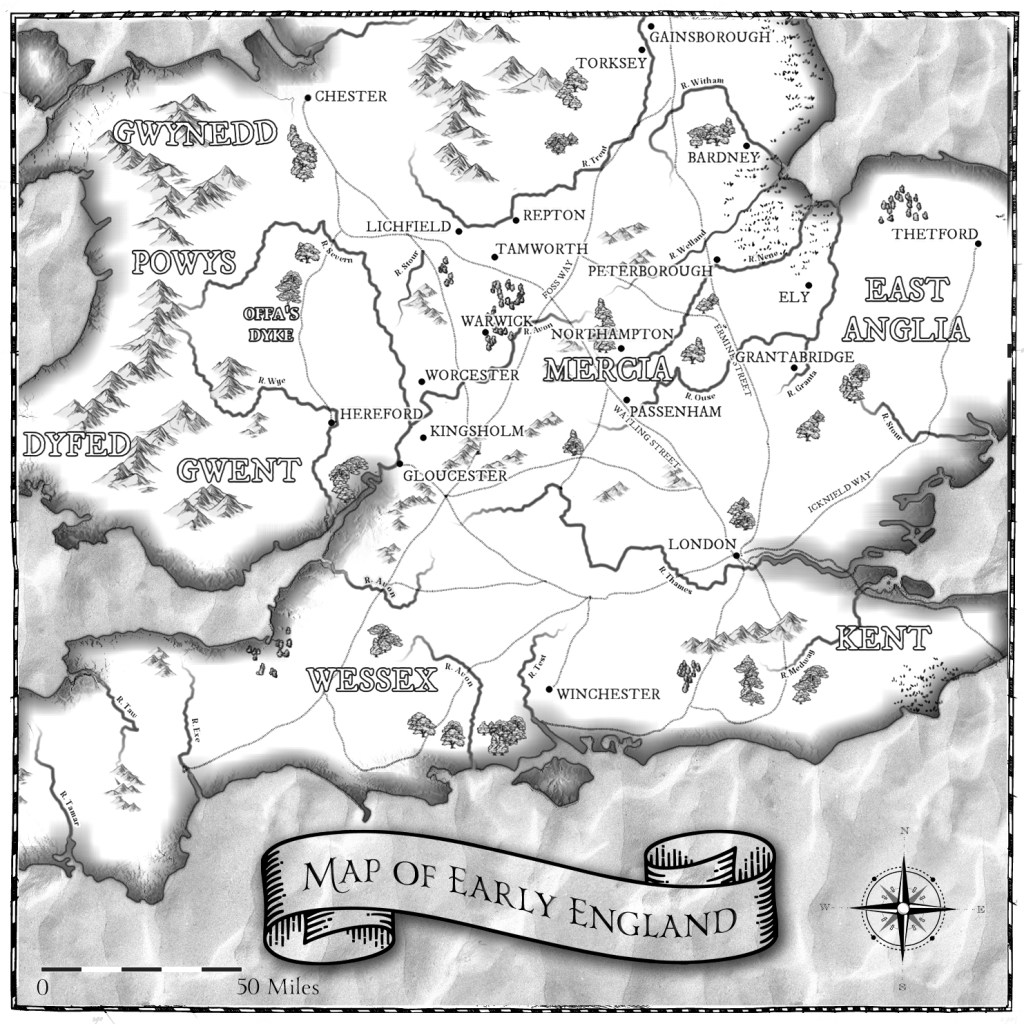

King Coelwulf of Mercia has unwillingly accepted the need to ally with the kingdom of Wessex under the command of King Alfred. But King Alfred of Wessex must still prove himself, and Coelwulf can’t remain absent from Mercia indefinitely.

Returning to London, a place holding more fascination for the West Saxons and the Viking raiders than Coelwulf and his fellow Mercians, Coelwulf sets about reinforcing the walled settlement so long abandoned by all but the most determined traders. But Coelwulf knows Jarl Guthrum has set his eyes on Canterbury, and he must protect the archbishop in Kent, nominally under the control of the West Saxon king, even if King Alfred is no warrior.

But deceit and lies run rife through the West Saxon camp and when Coelwulf believes he’s held to his oaths and alliances, an unexpected enemy might just sneak their way into Mercia. The future of Mercia remains at stake.

Purchase Link

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Last-Deceit-England-action-packed-historical-ebook/dp/B0DK3J8JVK

Available in ebook, paperback, hardback and the Clean(er) Editions, with much of the swearing removed.

The Last Deceit also includes a new short story.

If you’ve not discovered The Last King/The Mercian Ninth Century Series, then please check out the Series page on the blog.

Ealdorman Sigehelm and Cooling

In The Last Deceit, I’ve included a fictional character called Ealdorman Sigehelm, who is based on a later individual that we know existed, the father of Lady Eadgifu, third wife of Edward the Elder. (By based I mean I borrowed his name and landholding).

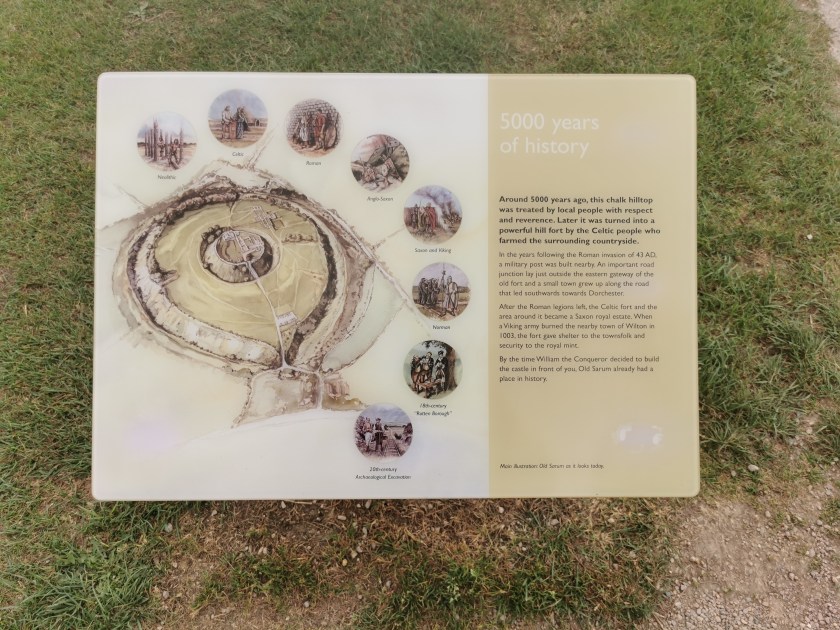

I’ve done this because it’s fun to play around with the information I’ve learned about later in the era. It’s often one of the biggest problems in writing historical fiction. You need to know what happens before the events you’re writing about, as well as what comes after, as well as the actual events you’re depicting. And Cooling, in Kent, has an incredibly detailed history throughout the later tenth century, which we know about because of a remarkable charter. The text of which is below (it’s quite long.)

‘Eadgifu declares to the archbishop and the community of Christ Church how her estate at Cooling came [to her]. That is, that her father left her the estate and the [land]book, just as he legally acquired them and his ancestors had bequeathed to him. It happened that her father borrowed thirty pounds from Goda, and entrusted the estate to him as security for the money. And [Goda] held it for seven ‘winters’. When it came about, at around this time, that all the men of Kent were summoned to the battle at the Holme, Sighelm [Sigehelm], her father, did not want to go to the battle with any man’s account unpaid, and he repaid Goda the thirty pounds and he bequeathed the estate to his daughter Eadgifu and gave her the [land]book. After he had fallen in the battle, Goda denied the repayment of the money, and withheld the estate until six years later. Then Byrhsige Dyrincg claimed it unceasingly for so long, until the Witan of that time commanded Eadgifu that she should purge her father’s possession by [an oath equivalent to] that amount of the money. And she produced the oath in the witness of all the people at Aylesford, and there purged her father’s repayment by an oath of thirty pounds. Then she was still not able to possess the estate until her friends obtained from King Edward [the Elder] that he prohibited him [Goda] the estate, if he wanted to possess any [at all]; and so he gave it up. Then it happened in the first place that the king so strongly blamed Goda that he was deprived of all the [land] books and property, all that he owned. And the king then granted him and all his property, with [land] books and estates, to Eadgifu to dispose of as she wished. Then she said that she did not dare before God to pay him back as he had deserved of her, and she restored to him all his land except the two sulungs at Osterland, and she refused to give back the [land] books until she knew how loyally he would treat her in respect of the estates. Then, King Edward died and Æthelstan [Athelstan] succeeded to the kingdom. When Goda thought it an opportune time, he sought out King Æthelstan and begged that he would intercede on his behalf with Eadgifu, for the return of his [land] books. And the king did so. And she gave back to him all except the [land] book for Osterland. And he willingly allowed her that [land] book and humbly thanked her for the others. And, on top of that as one of twelve he swore to her an oath, on behalf of those born and [yet] unborn, that this suit was for ever settled. And this was done in the presence of King Æthelstan and his Witan at Hamsey near Lewes [Sussex]. And Eadgifu held the land with the landbooks for the days of the two kings, her sons [i.e., Edmund and Eadred]. When Eadred died and Eadgifu was deprived of all her property, then two of Goda’s sons, Leofstan and Leofric, took from Eadgifu the two afore-mentioned estates at Cooling and Osterland, and said to the young prince Eadwig who was then chosen [king] that they had more right to them than she. That then remained so until Edgar came of age and he [and] his Witan judged that they had done criminal robbery, and they adjudged and restored the property to her. Then Eadgifu, with the permission and witness of the king and all his bishops, took the [land] books and entrusted the estates to Christ Church [and] with her own hands laid them upon the altar, as the property of the community for ever, and for the repose of her soul. And she declared that Christ himself with all the heavenly host would curse for ever anyone who should ever divert or diminish this gift. In this way this property came to the Christ Church community.’ S1211[i]

To explain:

Dating to around 959, the document provides the ownership history of an estate at Cooling in Kent. Eadgifu had inherited this land from her father, who had mortgaged it for a loan of £30, which he repaid before going on the campaign on which he died. However, Goda, the man who had made the loan, claimed not to have received payment and proceeded to take practical ownership of the estate. While Eadgifu retained the landbook, or freehold record, and tried various means of asserting her ownership, it was not until Edward the Elder intervened, presumably after their marriage, that the matter was resolved to some degree. Edward seized not only the estate in question but all Goda’s lands, handing their ownership and administration over to Eadgifu. The charter indicates that Eadgifu acted magnanimously, giving almost all of these back to Goda, though her primary consideration was likely to avoid creating a powerful political enemy. Sensibly, however, she retained possessions of the landbooks to ensure Goda’s loyalty, as well as a small estate at Osterland, in addition to her hereditary holdings at Cooling. The matter was fully resolved in Æthelstan’s [Athelstan] reign when the king interceded with Eadgifu on Goda’s behalf. Eadgifu returned the landbooks, but retained the estates at Osterland and Cooling, while Goda swore an oath in Æthelstan’s presence declaring that he considered the matter to be closed … Eadwig seized his grandmother’s landholdings and, in the case of the Cooling and Osterland estates, turned them over to Goda’s sons … After Eadwig’s death in 959, Edgar restored his aging grandmother’s possessions.[ii]

It’s unusual to have so much detail about a landed estate, and so, when I took Coelwulf and his allies to Kent in The Last Deceit, I couldn’t resist embroidering this character into the tale. I imagine you can see why. To read more about Lady Eadgifu, check out The Royal Women Who Made England.

[i] Sawyer, P.H. (ed.), Anglo-Saxon charters: An annotated list and bibliography, rev. Kelly, S.E., Rushforth, R., (2022). http://www.esawyer.org.uk/ S1211

[ii] Firth, M. and Schilling, C. ‘The Lonely Afterlives of Early English Queens’, in Nephilologus September 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11061-022-09739-4, pp.8–9