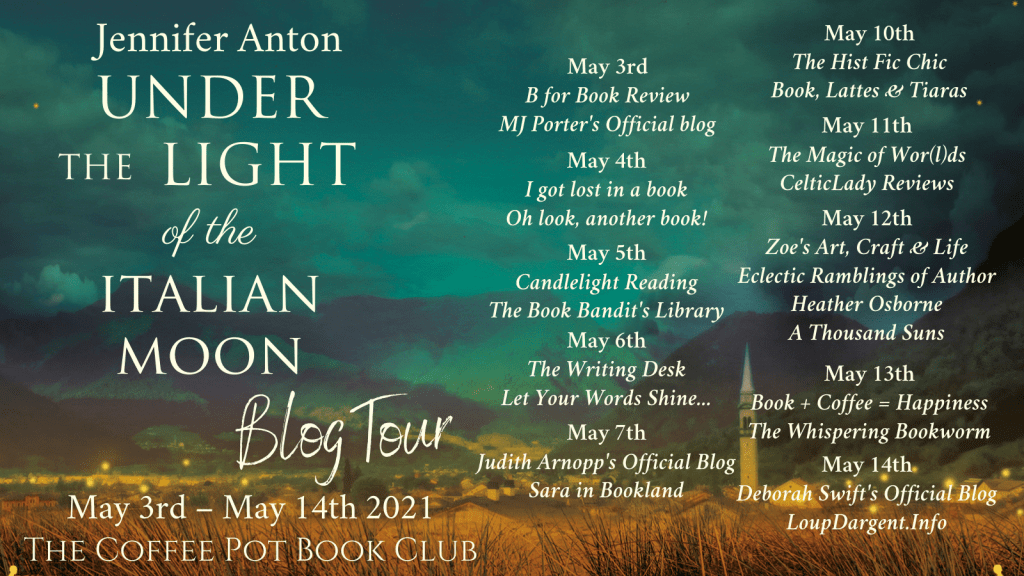

Today, I’m delighted to welcome Jennifer Anton to the blog, with a post about her historical research. (I love finding out all the details).

Your book, Under the Light of the Italian Moon, sounds fascinating, and the cover is beautiful. Can you explain your research process to me, and give an idea of the resources that you rely on the most (other than your imagination, of course) to bring the historical characters to life?

Thanks for having me on the blog and thank you for your kind words about the synopsis and cover of Under the Light of the Italian Moon.

I started researching the novel in 2006. My grandmother, who grew up in Italy and told me stories of her Nazi occupied hometown, got very ill before she could answer all the questions I had for her. Soon after, I had my daughter and ended up in heart failure. By the time I recovered, my grandmother died, never meeting my daughter. It was then that I decided to research her life and get answers to the questions left unanswered.

The first place I began was with her sister, my aunt, who had lived with her in Italy. Over coffee, we would sit for hours with my tape recorder and notebook. She then introduced me to people in the U.S., Canada and Italy who could tell me more. I spent hours on the phone and then took many trips to Fonzaso, Italy, where the novel takes place. My daughter accompanied me, first as a toddler, then as a little girl and then as a teenager, as we sat speaking to elderly Italians about my family, life under Mussolini and Nazi occupation. When I spoke with them, their stories came to life in my head. I did not see the older person in front of me, with grey hair and age spots. I saw them as my characters, full of life, surviving and living day to day under difficult times. It was a beautiful experience and every detail they gave me, I tried to include in the novel.

Researching with Aunt

While collecting first-hand accounts, I was also doing extensive research regarding the time frame. The novel covers a long period: starting in 1914, jumping to 1919 and then to 1923 and beyond. It allows the reader to see the progression of political forces in the background while we experience the life of Nina Argenta, the daughter of a strong-willed midwife who falls in love with a boy who has emigrated to the coal mines of America. I laid out the historical moments under the stories I was told and the other first hand research I was doing. A narrative began to form.

Do you have a ‘go’ to book/resource that you couldn’t write without having to hand, and if so, what is it?

The most important resources for me were both non-fiction and fiction. From a non-fiction perspective, Victoria De Grazia’s How Fascism Ruled Women and Perry Willson’s book about the Massaie Rurali were critical to understanding life for women during this time. Because the novel deals with a midwife as a central character, women’s reproductive rights, pressures and women in society were important for me to understand. As well, documents from Ellis Island, Fonzaso church records and websites documenting the fascist and Nazi atrocities in the area were incredibly useful.

But to fill the gaps for the historical fiction narrative, I needed to get into the hearts and minds of the characters. Non-fiction doesn’t help in that area. I sought out books from Bassani and Moravia and found a fantastic book of translated women’s stories from the time from Robin Pickering-Iazzi. This helped me sense check the life I was breathing into my characters for authenticity.

Over a fourteen-year period, I watched every film, read every book and generally filled my hours living in this time period. When I shut my office door, or opened my laptop, I was not in the place I sat, I was in Italy during the interwar years.

Fonzaso

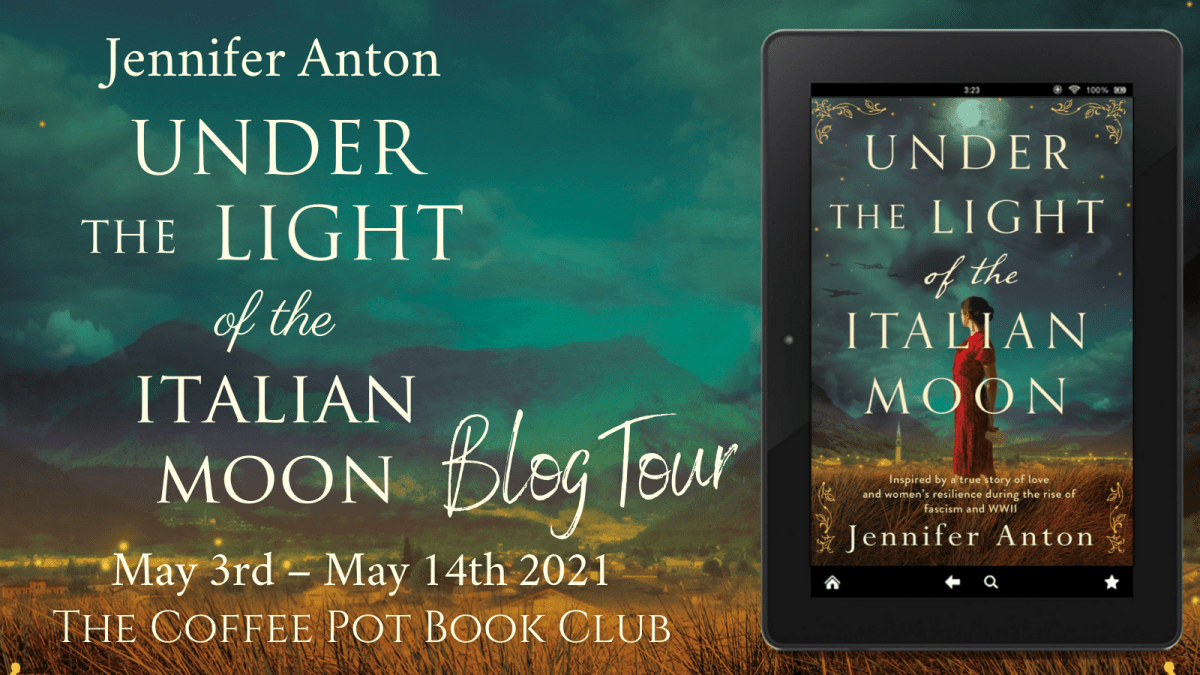

I hope my novel will also transport you into this time, into the life of Nina Argenta, her mother—a force of nature—Adelasia Dalla Santa Argenta and Nina’s beloved Pietro Pante. Come with me to Fonzaso and experience love and women’s resilience during the rise of fascism and WWII.

Thank you so much for sharing your fascinating journey with me. It sounds as though your research was both very personal and incredibly interesting.

Here’s the blurb;

A promise keeps them apart until WW2 threatens to destroy their love forever

Fonzaso Italy, between two wars

Nina Argenta doesn’t want the traditional life of a rural Italian woman. The daughter of a strong-willed midwife, she is determined to define her own destiny. But when her brother emigrates to America, she promises her mother to never leave.

When childhood friend Pietro Pante briefly returns to their mountain town, passion between them ignites while Mussolini forces political tensions to rise. Just as their romance deepens, Pietro must leave again for work in the coal mines of America. Nina is torn between joining him and her commitment to Italy and her mother.

As Mussolini’s fascists throw the country into chaos and Hitler’s Nazis terrorise their town, each day becomes a struggle to survive greater atrocities. A future with Pietro seems impossible when they lose contact and Nina’s dreams of a life together are threatened by Nazi occupation and an enemy she must face alone…

A gripping historical fiction novel, based on a true story and heartbreaking real events.

Spanning over two decades, Under the Light of the Italian Moon is an epic, emotional and triumphant tale of one woman’s incredible resilience during the rise of fascism and Italy’s collapse into WWII.

Amazon: Barnes & Noble: Waterstones:

Bookshop.org (U.S. only): I am Books Boston:

Meet the Author

Jennifer Anton is an American/Italian dual citizen born in Joliet, Illinois and now lives between London and Lake Como, Italy. A proud advocate for women’s rights and equality, she hopes to rescue women’s stories from history, starting with her Italian family.

Website: Twitter: Facebook: Instagram:

Pinterest: Book Bub: Amazon Author Page: