I’m sharing a fabulous post by Glen Craney below regarding the mistakes historical novelists must be wary of making.

Exposing History’s Cracks of Logic

Historical novelists are always prospecting for untapped veins in the strata of the past. Some of the richest lodes can be found in the lapses of logic and analysis that even the most astute of historians are at times prone to commit. Perhaps the best compilation of such errors in judgment and interpretation is Historians’ Fallacies, a treatise published in 1970 by Brandeis University professor David Hackett Fischer.

Readers of history will remember Fischer from Albion’s Seed, his exploration of the impact British folkways had on American society, and Washington’s Crossing, a study of George Washington’s leadership of the Continental Army.

Fischer’s impressive overview of historiography should be kept close at hand on the bookshelf of every historical novelist. Most of the miscalculations he skewers—exemplified by excerpts from the writings of his colleagues, many of whom no doubt chafed at being called to task—apply with equal force to the writing of historical fiction.

The best known of these gaffes gave its name to Fischer’s book: the historian’s fallacy. This refers to the error of assuming that the great leaders and decision-makers of the past possessed the same facts and perspective as we do in hindsight.

Fischer offered as an exhibit the popular claim that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor should have been foreseen from the numerous warning signs. He cautions historians against the tendency of sifting away evidence that, at the time, might have clouded one’s judgment or even supported a contrary opinion.

Likewise, historical novelists must be on their guard against attributing to their characters more knowledge of events than is warranted. It is easy enough for us to chastise Robert E. Lee for ordering Pickett’s charge. The task of both the historian and novelist is to recreate the fog of war at Gettysburg with such verisimilitude that the reader will come to understand why such a decision was rational on July 3, 1863.

The American Civil War seems to have served as the subject for every fallacy condemned by Fischer. Another infamous example castigated by Fischer is the discovery by Union scouts of the cigar-wrapped copies of Lee’s orders for the Antietam campaign. Every war buff has encountered the contention that this fortuitous (for the Union) incident set into motion a series of cascading events that eventually turned the tide of the war. Fischer dismisses this as a product of the reductive fallacy, which boils a complex soup of causal ingredients down into a single, simplified explanation.

In discussing another error, the fallacy of division (arguing that a quality shared by some in a group is shared by all), Fischer offers a faulty syllogism for our dissection:

Most Calvinists were theological determinists

Most New England Puritans were Calvinists.

Therefore, most New England Puritans were theological determinists.

Fischer observed that then-recent scholarship suggested the Puritans were not determinists, at least not as was commonly assumed. Here one finds a gold nugget, one of many available for the taking by the writer who will persist in combing these fallacies: A novel set in Puritan New England with a main character who believes in free will.

In The Da Vinci Code, Dan Brown made great use of yet another error that comes under special opprobrium from Fischer: the furtive fallacy. This is the assumption that certain events and facts of “special significance” are “dark and dirty things and that history itself is a story of causes mostly insidious and results mostly invidious.”

Of course, some of the best historical fiction would have to be tossed onto Savonarola’s bonfire if a ban on this fallacy were strictly enforced. Fischer doesn’t argue that conspiracies have never taken place. His criticism goes to a more fundamental paranoia that, if left unchallenged, can metastasize into a societal epidemic that weakens the very foundations of institutions.

It begins with the premise that reality is a sordid, secret thing; and that history happens on the back stairs a little after midnight, or else in a smoke-filled room, or a perfumed boudoir, or an executive penthouse or somewhere in the inner sanctum of the Vatican or the Kremlin, or the Reich Chancellery, or the Pentagon. It is something more, and something other than merely a conspiracy theory, though that form of causal reduction is a common component.

The furtive fallacy is a more profound error, which combines a naïve epistemological assumption that things are never what they seem to be, with a firm attachment to the doctrine of original sin.

Still, Professor Robert Langdon might remind his colleague Dr. Fischer that just because one is paranoid doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you.

The historical novelist is not only free but compelled to adopt and exploit these rich fallacies to spin out a good story—so long as he does so consciously.

Thank you for sharing:)

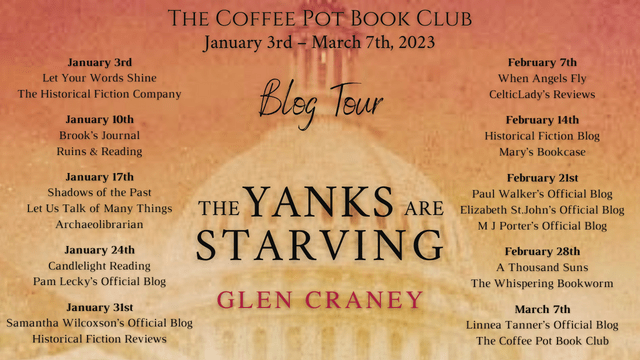

Here’s the blurb

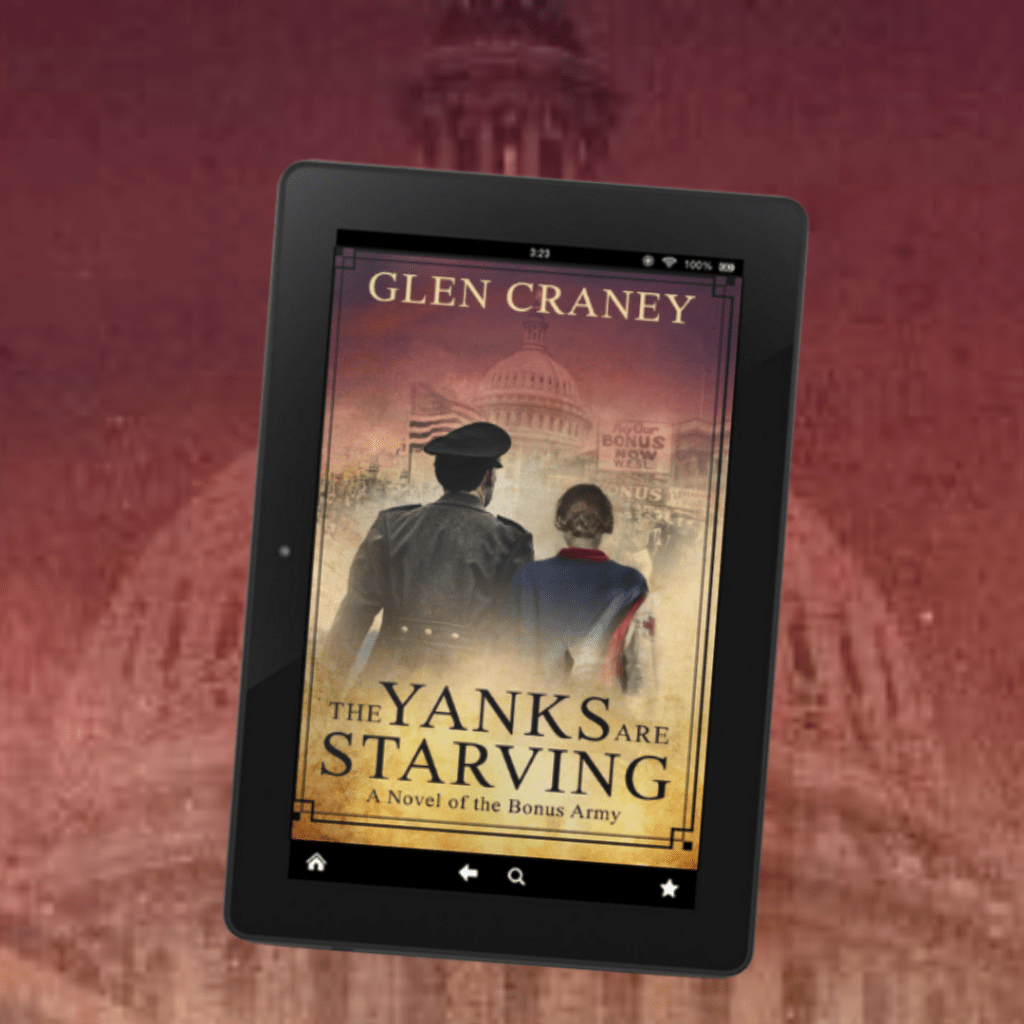

Two armies. One flag. No honor.

The most shocking day in American history.

Former political journalist Glen Craney brings to life the little-known story of the Bonus March of 1932, which culminates in a bloody clash between homeless World War I veterans and U.S. Army regulars on the streets of Washington, D.C.

Mired in the Great Depression and on the brink of revolution, the nation holds its collective breath as a rail-riding hobo named Walter Waters leads 40,000 destitute men and their families to the steps of the U.S. Capitol on a desperate quest for economic justice.

This timely epic evokes the historical novels of Jeff Sharra as it sweeps across three decades following eight Americans who survive the fighting in France and come together fourteen years later to determine the fate of a country threatened by communism and fascism.

From the Boxer Rebellion in China to the Plain of West Point, from the persecution of conscientious objectors to the horrors of the Marne, from the Hoovervilles of the heartland to the pitiful Anacostia encampment, here is an unforgettable portrayal of the political intrigue and government betrayal that ignited the only violent conflict between two American armies.

Awards

Foreword Magazine Book-of-the-Year Finalist

Chaucer Award Book-of-the-Year Finalist

indieBRAG Medallion Honoree

Praise for The Yanks are Starving

“[A] wonderful source of historical fact wrapped in a compelling novel.” — Historical Novel Society Reviews

“[A] vivid picture of not only men being deprived of their veterans’ rights, but of their human rights as well.…Craney performs a valuable service by chronicling it in this admirable book.” — Military Writers Society of America

Buy Links

Amazon US: Amazon UK: Amazon CA: Amazon AU:

Barnes and Noble: Kobo: iBooks:

Meet the Author

Glen Craney is an author, screenwriter, journalist, and lawyer. A graduate of Indiana University Law School and Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, he is the recipient of the Nicholl Fellowship Prize from the Academy of Motion Pictures and the Chaucer and Laramie First-Place Awards for historical fiction. He is also a four-time indieBRAG Medallion winner, a Military Writers Society of America Gold Medalist, a four-time Foreword Magazine Book-of-the-Year Award Finalist, and an Historical Novel Society Reviews Editor’s Choice honoree. He lives in Malibu and has served as the president of the Southern California Chapter of the HNS.

Connect with Glen

Facebook: LinkedIn: Pinterest:

BookBub: Amazon Author Page: Goodreads:

Check our Glen’s other visits to the blog.