Here’s the blurb

A King in crisis, a Queen on trial, a Kingdom’s survival hangs in the balance.

Londonia, AD835

The deadly conspiracy against the children of Ealdorman Coenwulf is to be resolved. Those involved have been unmasked and arrested. But will justice prevail?

While the court convenes to determine the conspirator’s fate, King Wiglaf’s position is precarious. His wife, Queen Cynethryth, has been implicated in the plot and while Wiglaf must remain impartial, enemies of the Mercia still conspire to prevent the full truth from ever being known.

As Merica weeps from the betrayal of those close to the King, the greedy eyes of Lord Æthelwulf, King Ecgberht of Wessex’s son, pivot once more towards Mercia. He will stop at nothing to accomplish his goal of ending Mercia’s ruling bloodline.

Mercia once more stands poised to be invaded, but this time not by the Viking raiders they so fear.

Can Icel and his fellow warriors’ triumph as Mercia once more faces betrayal from within?

An action packed, thrilling historical adventure perfect for the fans of Bernard Cornwell and Matthew Harffy

Here’s the purchase link (ebook, paperback, hardback and audio)

books2read.com/BetrayalofMercia

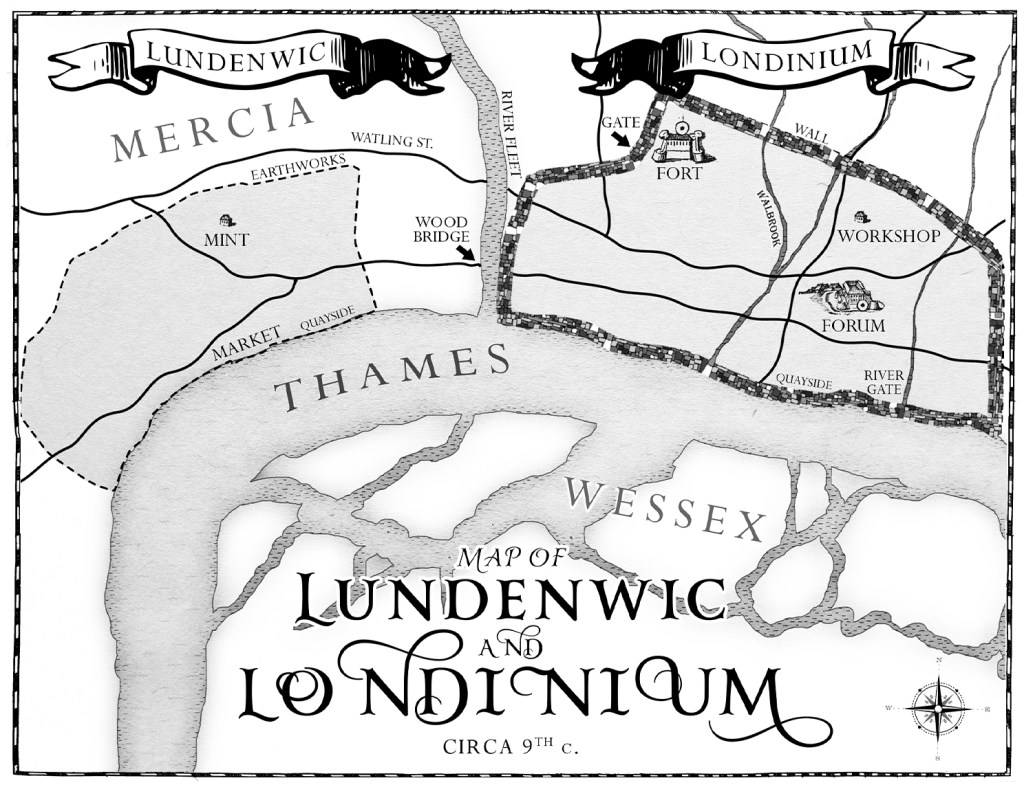

Maps

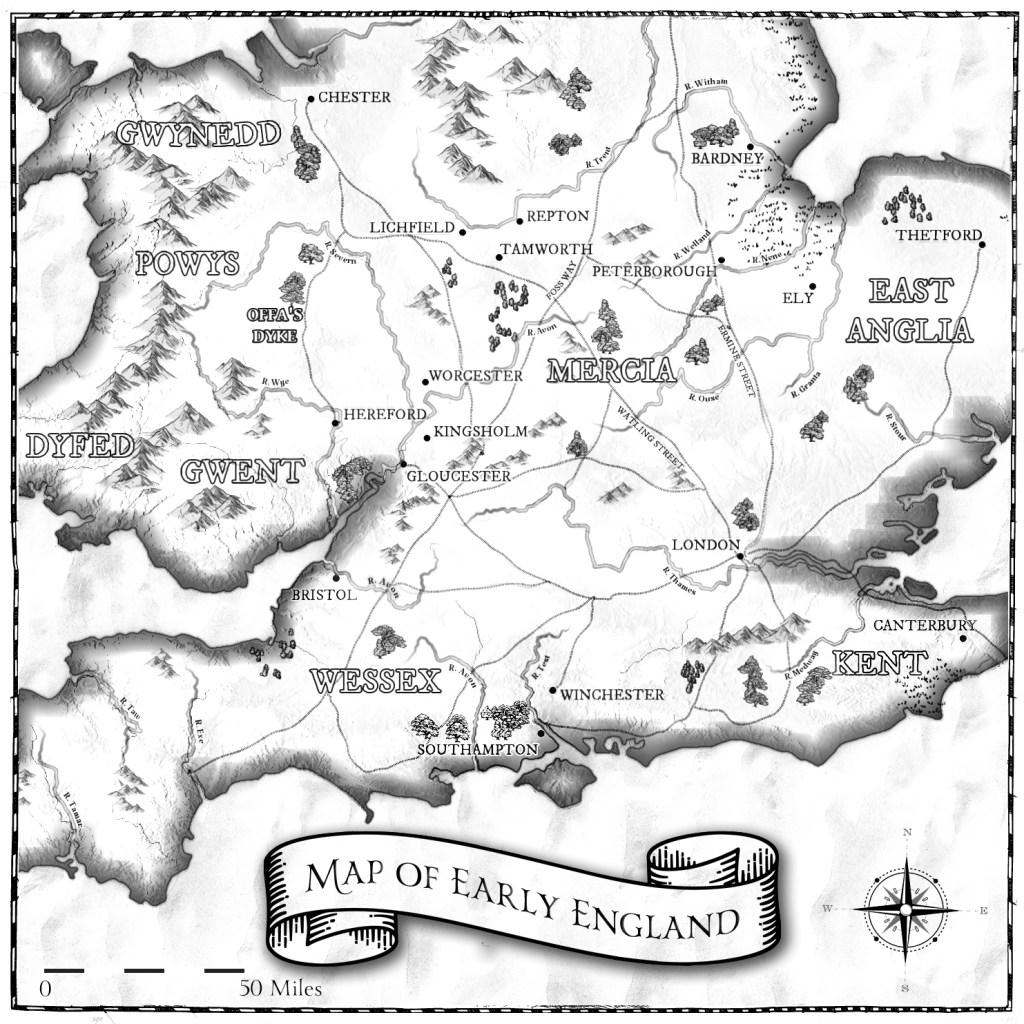

Throughout the series I’ve taken young Icel to some interesting locations, and that means I’ve had to make use of many maps which are recreations of the era, because, alas, we have none from the period. Both maps I’ve had made are relevant to Betrayal of Mercia which largely takes place in London, or Londonia, or Londinium and Lundenwic.

The map of Lundenwic and Londinium, shortened in the books to Londonia, a term more accurately applied to the eighth century and not the ninth, is much simplified and largely shows locations relevant to me and which I need to remember when writing the books. Although, I must confess, I did forget about it in the drafting process and when I found it, I was relieved to discover I hadn’t made THAT many mistakes.

The most important elements to understand are that ‘London’ as we know it didn’t exist at this time. Instead, there were two very distinctive settlements, and they were seperated by the River Fleet, one of London’s ‘lost’ rivers because it’s now subterranean. I think, for me, not being very familiar with London as it is today actually helped. Rather than trying to orientate myself as to what’s there now, I can work the other way round. I sort of know what was and wasn’t there in the ninth century, and then I can try and work out what’s there now:) Honestly, it makes sense to me.

It also helps to remember that despite London now being the capital of England, it wasn’t in the ninth century. Far from it, in fact. There are many good books on London in it’s earliest manifestations. If you’re interested, they are very worth checking out.

I also have a map of England at this time. This is to help readers (and me) try and get an idea of what settlements were and weren’t there at the time. As I’ve learned, it can be far too easy to just assume the longevity of a location, and then discover it wasn’t there at all, was bigger or even, much smaller than it is now. One of those locations is Wall, close to Lichfield, which was very important during the Roman occupation of Britain, but is now little more than ruins. And it’s far from alone in that.

I’ll also be sharing more posts, including one on Mercia’s ‘Bad Queens,’ and one on Crime and Punishment in Saxon England.

Not started the series yet? Check out the series page on my blog.

Check out the blog tour for Betrayal of Mercia

A huge thank you to all the book bloggers and Rachel at Rachel’s Random Resources for organising.