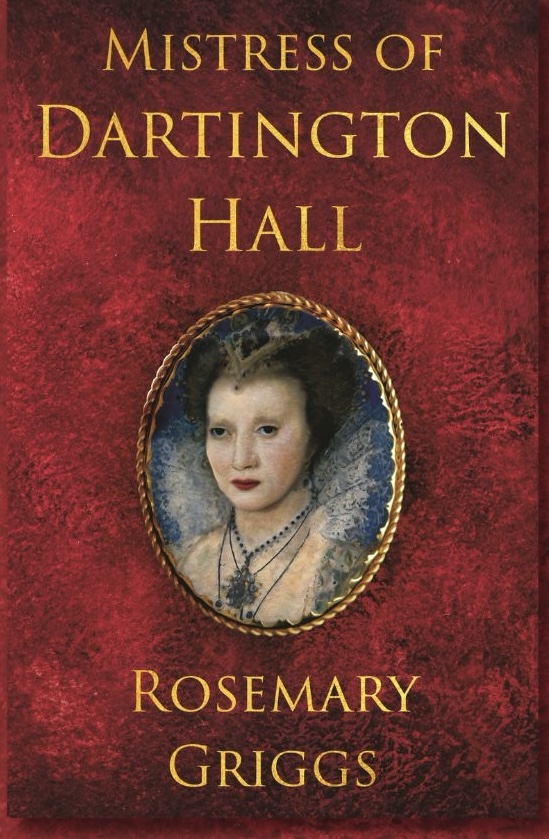

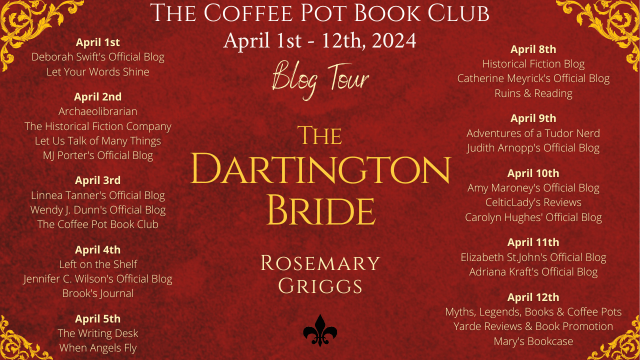

I’m delighted to welcome Rosemary Griggs and her book, Mistress of Dartington Hall, Book 3 in the Daughters of Devon series, to the blog with a guest post.

Guest Post – historical background

Mistress of Dartington Hall continues the story of a French Huguenot noblewoman, Lady Gabrielle Roberda Montgomery. Roberda’s father, Gabriel de Lorges, was a prominent Huguenot general. He gained notoriety as the man who accidentally killed King Henry II of France in a jousting accident.

Roberda married into one of Devon’s most prominent families. Her husband, Gawen Champernowne’s was the son of Sir Arthur Champernowne, a staunch Protestant. Sir Arthur was Queen Elizabeth’s Vice-Admiral of the Fleet of the West, and he had connections at court.

We followed Roberda’s traumatic childhood in war-torn France and her catastrophic marriage to Gawen in The Dartington Bride. In Mistress of Dartington Hall we join her in the autumn of 1587. Roberda has been managing Dartington Hall while her estranged husband, Gawen, has been away on the Queen’s business.

England has been at war with Spain for over two years. The Spanish king is preparing a formidable fleet of warships to launch an invasion. In 1587, everyone expected them to land at Falmouth, Plymouth or Dartmouth to establish a foothold on English soil. Thousands of Spanish soldiers would then disembark and rampage through the countryside. It must have been a terrifying time for the people of Dartington, only sixteen miles upriver from the port of Dartmouth. Many panic-inducing false alarms disturbed the people of Devon before the Spanish Armada’s arrival in July 1588.

Relations between England and Spain had been tense for a long time. After his wife, Queen Mary, died childless in 1558, Philip of Spain proposed to her sister, the new Queen Elizabeth. Elizabeth declined the offer, and Philip married elsewhere.

King Philip’s marriage to Elisabeth of Valois, the daughter of King Henry II of France, cemented the end of a long war between France and the Habsburgs. It was during the joust that accompanied the celebrations in Paris in the summer of 1559 that Roberda’s father’s lance shattered. His opponent, King Henry, had not put down his visor. A splinter of wood entered the king’s eye, and he died 11 days later. That accident changed the course of Gabriel’s life. It also set off the chain of events that brought Roberda to Dartington Hall.

After Queen Elizabeth I established a Protestant church in England, King Philip considered it his duty to return England to the Catholic faith. That, combined with political rivalry and economic competition, stoked his ambition to conquer England. He amassed a massive fleet of warships and gathered supplies.

In 1570, Pope Pius V excommunicated Elizabeth. The Pope supported Philip’s plan by promising forgiveness to those who took part in the invasion. Audacious English privateering raids on Spanish ships led by people like Sir Francis Drake made King Philip even more determined. The frequent attacks on Spanish ships and colonies disrupted Spanish trade and wealth. After the Treaty of Nonsuch, signed in 1585, confirmed England’s support for the Protestant Dutch rebels against Spanish rule, Philip put his plans in motion.

Sir Francis Drake’s audacious raid on Cadiz, known as ‘singeing the King of Spain’s beard’, destroyed around 30 Spanish ships and supplies, delaying the Armada’s launch by over a year. But everyone knew they would come.

England prepared, hoping the new English ships, faster and more manoeuvrable than the cumbersome Spanish galleons, would give them an advantage. However, Queen Elizabeth was notoriously parsimonious, leaving the English fleet short of powder and shot. Her reluctance to spend money frustrated her advisors, including the commander of the English fleet, Charles Howard.

Drake gathered ships at Plymouth, ready to meet the Spanish. However, many of his sailors fell ill and died from lack of food and cramped, unsanitary conditions on board. More men had to be conscripted from the surrounding area to replace them.

Sir Walter Raleigh’s network of warning beacons would signal the approach of the Spanish fleet. The Lord Lieutenant and his deputies mustered a militia — a sort of ‘Dad’s Army’ of poorly equipped, untrained militia-men. Roberda’s husband, Gawen Champernowne, was to lead cavalrymen drawn from the local nobility. These last-minute preparations would likely have proved inadequate had the invaders stuck to their initial plan.

Luckily, the Spanish commander decided to rendezvous with the Duke of Parma rather than first landing in the southwest. The Armada sailed on up the English Channel, pursued by Drake’s ships. At Gravelines, Drake sent in fire-ships to disrupt their formation. But it was bad weather that finally defeated King Philip’s attempt on England. The ‘Protestant Wind’ scattered them, driving them around the coast of Scotland. Some foundered on rocks; a few limped home to Spain. On land, Gawen Champernowne, who was to have led a cavalry troop against the expected attack, went home having seen no action.

The Armada failed in 1588, but the conflict continued for another sixteen years. In August 1595, the Spanish raided and burned villages in Cornwall. They attempted two more full-scale expeditions in 1596 and 1597. Roberda and the people of Devon continued to live with the threat of invasion. The war finally ended with the Treaty of London in 1604.

Meanwhile, in France, Roberda’s brothers sought to reclaim the estates they lost when their father died on the executioner’s block in Paris in 1574. The French Wars of Religion escalated into the War of the Three Henrys. Henry of Navarre became King Henry IV after both the Duke of Guise, leader of the Catholic League, and King Henry III, were assassinated.

During the 1590s Roberda’s brothers supported Henry IV in his campaigns to assert his authority. He faced opposition from the Catholic League, which Spain supported. Eventually, Henry IV publicly converted to Catholicism, and in 1594 he entered Paris, weakening the Catholic League. A year later. Henry IV formally declared war on Spain. The Edict of Nantes, issued in 1598, ended the religious wars in France. Catholicism became the state religion, but the Huguenots had substantial rights and religious freedoms. Roberda’s family reclaimed their lands. After her mother’s death, Roberda received her share, and her younger brother, Gabriel, eventually rebuilt the family home at Ducey.

Roberda’s life as Mistress of Dartington Hall, played out against an uncertain background. England was at war with Spain, and Devon was on the ‘front line’. Religion continued to divide her home country, France. Like many women of her time, she successfully managed a vast estate while Gawen was away. She overcame the hostility that met her in England as an incomer. Roberda gained the respect and trust of her estate workers, tenants and servants. Gawen’s return jeopardised her hard-won authority and put her in a difficult position. Should she trust him? Later, Roberda takes decisive action to secure her children’s inheritance. But can she eventually grasp the chance of happiness for herself?

Here’s the Blurb

1587. England is at war with Spain. The people of Devon wait in terror for King Philip of Spain’s mighty armada to unleash untold devastation on their land.

Roberda, daughter of a French Huguenot leader, has been managing the Dartington estate in her estranged husband Gawen’s absence. She has gained the respect of the staff and tenants who now look to her to lead them through these dark times.

Gawen’s unexpected return from Ireland, where he has been serving Queen Elizabeth, throws her world into turmoil. He joins the men of the west country, including his cousin, Sir Walter Raleigh, and his friend Sir Francis Drake, as they prepare to repel a Spanish invasion. Amidst musters and alarms, determined and resourceful Roberda rallies the women of Dartington. But, after their earlier differences, can she trust Gawen? Or should she heed the advice of her faithful French maid, Clotilde?

Later Roberda will have to fight if she is to remain Mistress of Dartington Hall, and secure her children’s inheritance. Can she ever truly find fulfilment for herself?

Buy Link

Meet the Author

Author and speaker Rosemary Griggs has been researching Devon’s sixteenth-century history for years. She has discovered a cast of fascinating characters and an intriguing network of families whose influence stretched far beyond the West Country. She loves telling the stories of the forgotten women of history — the women beyond the royal court; wives, sisters, daughters and mothers who played their part during those tumultuous Tudor years: the Daughters of Devon.

Her novel, A Woman of Noble Wit, set in Tudor Devon, is the story of the life of Katherine Champernowne, Sir Walter Raleigh’s mother. The Dartington Bride, follows Lady Gabrielle Roberda Montgomery, a young Huguenot noblewoman, as she travels from war-torn France to Elizabethan England to marry into the prominent Champernowne family. Mistress of Dartington Hall, set in the time of the Spanish Armada, continues Roberda’s story.

Rosemary is currently working on her first work of non-fiction — a biography of Kate Astley, childhood governess to Queen Elizabeth I, due for publication in 2026.

Rosemary creates and wears sixteenth-century clothing, and brings the past to life through a unique blend of theatre, history and re-enactment at events all over the West Country. Out of costume, Rosemary leads heritage tours at Dartington Hall, a fourteenth-century manor house that was home of the Champernowne family for 366 years.

Connect with the Author